In a nutshell

A number of phenomena happening around the world will shape the likely features of the coming phase of regionalism: rising protectionism; geopolitical tensions; economic instability; and a new form of quasi-regionalism.

It is extremely unlikely that there will be a leap forward in trade liberalisation in general and regional integration specifically in the coming period; conventional regional trade liberalisation for Arab countries, whether inter- or intra-regional, is expected to be in the back seat.

Instead, Arab countries should fix their structural imbalances and focus more on enhancing their productivity and getting engaged in global and regional value chains; in that way, they will be ready for the next phase of trade prospects, which at this stage is difficult to identify.

Research on regional integration in the Arab world has typically focused on whether regional trade agreements have achieved what is expected in terms of enhancing intra-regional trade within the Arab region or between the Arab countries and their major trading partners, the United States and the European Union (EU). Most of the analysis has concluded that the potential for enhancing intra-regional trade remains to be reaped – and that doing so requires deepening of such agreements (for example, Galal and Hoekman, 1997, 2003).

At the same time, regionalism has been subject to extensive changes across the world. Chronologically, its history can be classified into three main phases starting from the mid-1980s:

- The first phase, which lasted from 1985 to 1995, revolved mainly around the choice between multilateralism and regionalism (Bhagwati, 1992).

- The second phase, which lasted from 1996 to 2005, focused mainly on the choice between shallow versus deep integration (Lawrence, 1996).

- The third phase, which lasted from 2006 to 2015, involved attempts to add further issues to deep integration in a trial and error approach that included investment and services (Chauffour and Maur, 2011).

From 2016 onwards, a new phase of regionalism began for both the world and the Arab region. The focus of this column is on this phase, mainly discussing its features, and trying to draw a road map for the Arab world based on the expectations for this phase.

A number of phenomena happening around the world shape our view of the likely features of the coming phase of regionalism: rising protectionism; geopolitical tensions; economic instability; and a new form of quasi-regionalism.

Protectionism is rising everywhere

The trade war between the United States and China, which was triggered during the Trump administration, has led to the adoption of widespread beggar thy neighbour policies against trading partners. It began with the safeguard measures adopted by the United States against steel and aluminium imports imposed in 2018. The EU followed suit, initiating similar policies in 2019.

In the same period, the NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was renegotiated from 2017 to include more protectionist measures, and a slogan of ‘America First’ was announced by President Trump (Wittner, 2024). This implied that the traditional guardians of trade liberalisation were retreating from their commitment to free trade, signalling a new wave of increased protectionism across the world.

The Arab region was heavily affected by these policies, notably those countries that are significant exporters of steel and aluminium: Bahrain, Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Moreover, the EU’s new CBAM (carbon border adjustment mechanism) initiative can be considered as a non-tariff barrier although disguised in the form of protection from the effects of climate change (Ghoneim, 2024).

Political tensions

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to the breaking of several trade and investment rules as economic sanctions were imposed by the West on Russia. This threw doubt on the future of trade liberalisation where the economy in general and trade specifically follow the political scene. Hence, the prospects for regional trade cooperation between the EU and Russia were broken and very difficult to restore. Moreover, global value chains have been negatively affected by the war in Ukraine (KPMG, 2022).

The world is also experiencing deviation from mainstream politics. Europe, Latin America and other regions have seen the rise of extreme political directions, and all are moving away from trade liberalisation, whether extreme right or left.

At the same time, the Arab world has suffered different types of political tensions, whether in the form of civil wars, domestic unrest or the ‘failed state’ status of a number of countries. All of this throws doubt on the meaning of regional integration in a region where at least a quarter of the 22 members of the League of Arab States and the 18 members of the Pan Arab Free Trade Area are considered ‘conflict countries’.

Unstable economic conditions

The unstable economic conditions worldwide arising from a series of crises – from the Covid-19, through the rise in interest rates to tackle an unprecedented inflation wave, to the cutting of supply chains due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – have created much uncertainty and led many countries to lean towards protectionism. The Arab region was among those most severely affected by the crises in the form of capital flight, higher import bills for raw materials and basic food staples, and unstable oil prices (ESCWA, 2022).

The rise of new forms of quasi-regionalism

The evolution of the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) as a new forum to enhance economic, political and cultural relationships between its members (together with its extension in 2023 to include an additional four members, including two Arab countries) represents a deviation from the traditional type of regional integration. Trade liberalisation is not on the agenda of the BRICs, yet the extent and growth of trade volumes among its members raises questions about the need to liberalise trade within the context of traditional regional integration agreements.

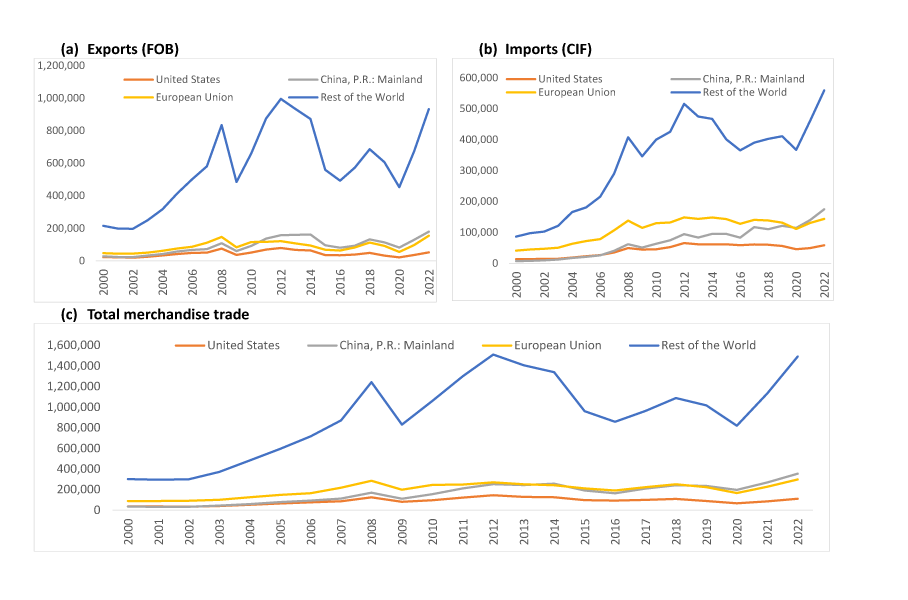

As Figure 1 shows, the extent of trade of Arab countries (proxied here by the Middle East due to data availability) with China versus the equivalent of trade of Arab countries with the EU, the United States and the rest of the world (with which a number of Arab countries have regional trade agreements), together with the rate of growth of trade with China, emphasise that trade can grow even in the absence of regional trade agreements. Moreover, the features of the world identified above signal a deviation from embarking on new regional trade agreements at this stage or a deepening of the existing ones.

Figure 1: Merchandise trade of the Middle East with China, the EU, the United States and the rest of the world (2000-22)

Source: Direction of Trade Statistics, International Monetary Fund.

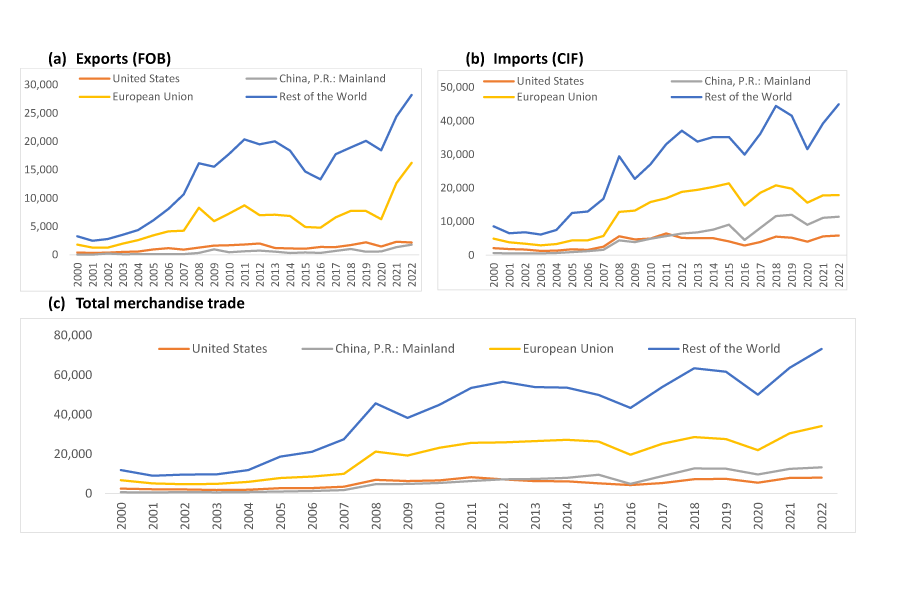

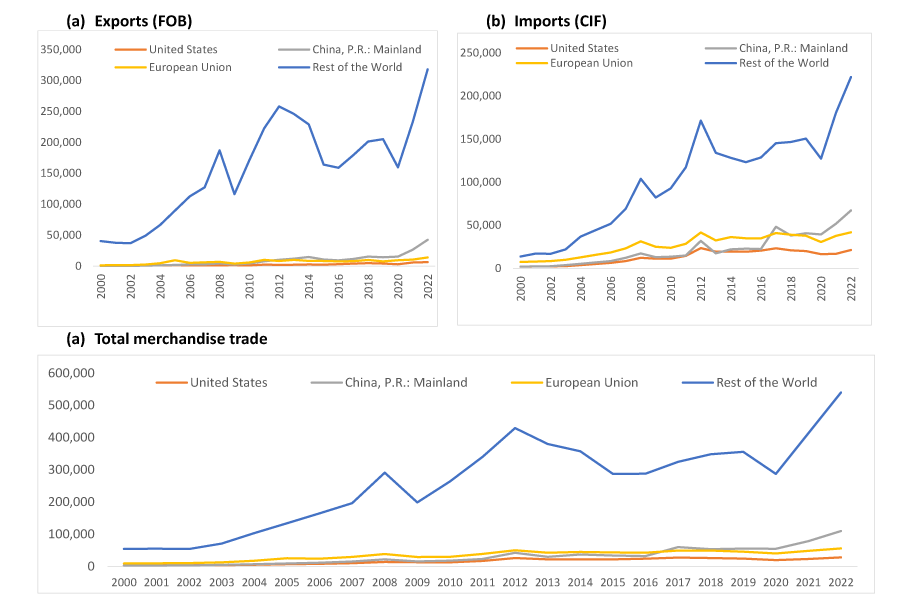

Figures 2 and 3 confirm the trends observed in the Middle East as a whole for two individual Arab countries: Egypt and the UAE. Despite the fact that the level of trade between Egypt/the UAE and China is lower than the equivalent for EU, the United States and the rest of the world, the rate of growth of trade between Egypt/the UAE and China is higher, in the majority of cases, than the rate of growth of trade between Egypt/the UAE and China compared with the EU, the United States and rest of the world.

Figure 2: Merchandise trade of Egypt with selected areas and China (2000-22)

Source: Direction of Trade Statistics, International Monetary Fund.

Figure 3: Merchandise trade of the UAE with selected areas and China (2000-22)

Source: Direction of Trade Statistics, International Monetary Fund.

The way forward

The substantial increase of trade with the East in general, and China specifically, albeit the rareness or absence of formal regional trade agreements between Arab countries and such pivotal economic and trade bulk implies that traditional trade agreements are subject to question. As with the whole world the trade of Arab countries is increasing at unprecedented levels with the East, and specifically China without trade liberalisation.

Hence, it is not expected that Arab countries will pursue any type of regional trade agreements with the East where trade is increasing with no agreements needed. If any trade agreements are concluded, it will result in escalating the negative trade balance between Arab countries and the East.

Moreover, in light of the aforementioned factors, it is extremely unlikely that Arab countries will embark on any new agreements. For their existing agreements, it is not expected that that they will increase the coverage of such agreements or shift from shallow to deep agreements.

In fact, as the model of renegotiating the NAFTA shows, the opposite is happening. Even Arab countries that were offered ‘deep and comprehensive free trade agreements’ (DCFTAs) by the EU from 2015 onwards – namely Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia, Jordan – have not concluded any such agreements.

It is extremely difficult to expect a leap forward in trade liberalisation in general and regional integration specifically, whether on an inter- or intra-regional level. Conventional regional trade liberalisation for Arab countries is expected to be in the back seat for the coming period.

Instead, Arab countries should fix their structural imbalances and focus more on enhancing their productivity and getting engaged in global and regional value chains. In that way, they will be ready for the coming phase of trade prospects, which at this stage are difficult to identify.

Further reading

Bhagwati, Jagdish (1992) ‘Regionalism versus Multilateralism’, The World Economy 15(5): 535-56.

Chauffour, Jean-Pierre, and Jean-Christophe Maur (2011) ‘Beyond Market Access’, in Preferential Trade Agreement Policies for Development: A Handbook edited by Jean-Pierre Chauffour and Jean-Christophe Maur, World Bank.

ESCWA, Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2022) Impacts of the war in Ukraine on the Arab region.

Galal, Ahmed, and Bernard Hoekman (eds) (2003) Arab Economic Integration between Hope and Reality, Brookings Institution Press.

Galal, Ahmed, and Bernard Hoekman (eds) (1997) ‘Regional Partners in Global Markets: Limits and Possibilities of the Euro-Med Agreements’, Centre for Economic Policy Research and the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies.

Ghoneim, Ahmed Farouk (2024) ‘EU climate policy: potential effects on the exports of Arab countries’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

Lawrence, Robert Z (1996) Regionalism, Multilateralism, and Deeper Integration, Brookings Institution Press.

KPMG (2022), ‘Immediate and long-term impacts of the Russia-Ukraine was on supply chains’. Wittner, Lawrence (2024) ‘The Ugly Origins of Trump’s America First Policy’, Foreign Policy in Focus.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.