In a nutshell

Sanctions have a significant negative effect on energy efficiency across 24 industrial sub-sectors of the Iranian economy; for example, if our calculated measure of sanction intensity shifts from low to high, the efficiency of energy use is expected to decrease by 3.16%.

One channel for the impact of sanctions is that by blocking the import of modern equipment and technologies (or increasing their funding costs), they force target countries to rely on outdated equipment; dependence on obsolete technologies inevitably results in a decline in energy efficiency.

The negative effects of sanctions are particularly significant in industries with higher import dependence; these sectors, which rely more on international markets for their inputs and production, experience greater declines in energy efficiency due to sanctions.

Iran is one of the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world – and a growing body of research has examined the impact of sanctions on various macroeconomic indicators.

These studies include analysis of the effects of sanctions on the formal economy (Laudati and Pesaran, 2023), the informal economy (Farzanegan, 2013; Farzanegan and Hayo, 2019; Farzanegan and Fischer, 2021; Zamani et al, 2021; Moghaddasi Kelishomi and Nisticò, 2023), household welfare and women’s employment (Farzanegan et al, 2016; Demir and Tabrizy, 2022; Ghomi, 2022), government expenditures and revenues (Farzanegan, 2011; Dizaji, 2014), militarisation (Dizaji and Farzanegan, 2021; Farzanegan, 2022), trade (Haidar 2017), finance (Torbat 2005) and carbon emissions (Balali et al, 2024).

But the sectoral effects of sanctions warrant further examination, as highlighted in a review by Farzanegan and Batmanghelidj (2023). Our new study contributes to addressing this gap in the research evidence by analysing the sectoral impact of sanctions on energy efficiency in 24 selected industrial sub-sectors between 2015 and 2019 (Jabari et al, 2024). Our analysis shows a significant negative effect of sanctions on energy efficiency, especially in sectors with high import dependence.

Potential effects of economic sanctions on energy efficiency

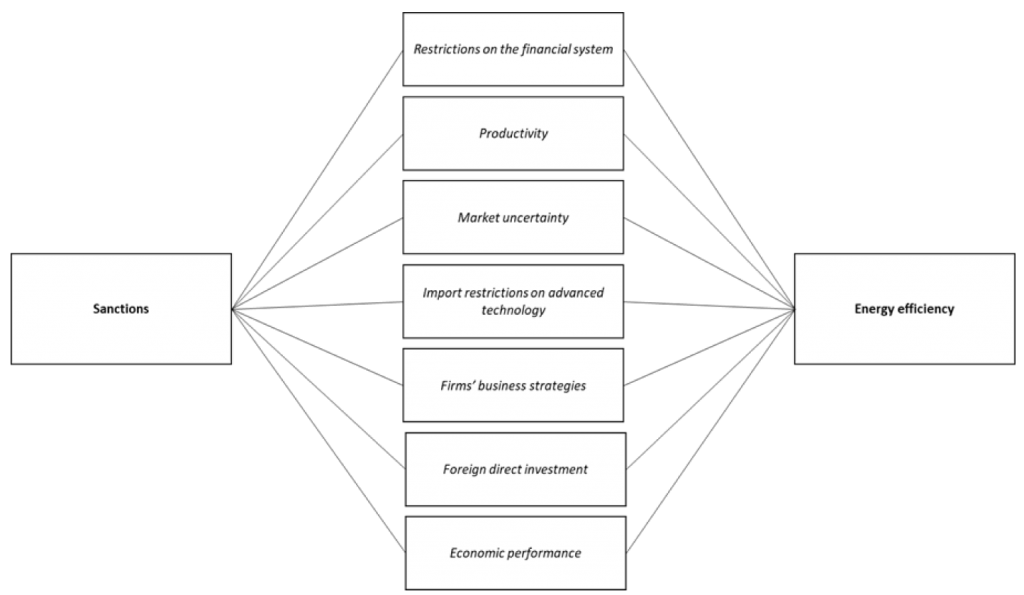

Economic sanctions can reduce energy efficiency through various channels. Figure 1 illustrates the key pathways through which this negative impact can occur.

Sanctions limit access to financial systems and restrict funding for energy-efficient technologies. The adoption of new technologies helps to optimise consumption of fossil fuels, promotes the use of clean energy and lowers emissions without sacrificing economic output.

Given the crucial role of technological progress in enhancing energy efficiency, it becomes evident that sanctions, by blocking the import of modern equipment and technologies (or increasing the cost of their funding), force target countries to rely on outdated equipment. This dependence on obsolete technologies inevitably results in a decline in energy efficiency (Chen et al, 2019).

Sanctions can also lead to a decline in the productivity of factors of production. Research shows that sudden restrictions on market access due to sanctions can reduce firm productivity, especially in industries that depend on imported inputs. As a result, firms may seek to cut costs by shifting their workforce to the informal sector (Moghaddasi Kelishomi and Nisticò, 2023).

In this context, some manufacturing units may exit the formal economy and move to the informal sector, reducing output in the formal sector. This decrease in formal output, combined with the growth of the informal economy, can increase energy consumption per unit of output, thereby lowering energy efficiency. Both formal and informal sectors consume energy inputs, but only formal output is recorded. As a result, sanctions can cause firms to become technically inefficient, meaning they produce less output than would be possible with the available inputs.

Market uncertainty, intensified by sanctions, significantly affects firms’ decisions about their activities, production and investment. Investing in energy-efficient and sustainable energy projects often requires substantial initial capital and long-term planning, both of which become more challenging in an environment of sanction-driven economic uncertainty.

Changes in firm behaviour under sanctions can also have long-term negative effects on the efficiency of firms. A case study of Iran shows that one survival strategy that Iranian firms adopted during sanctions was to cut spending on research and development, R&D (Cheratian et al, 2023).

Sanctions reduce the GDP of target countries (Gutmann et al, 2023) and raise the cost of doing business in the formal economy. This often leads governments to increase taxes to offset budget deficits, especially due to lost exports of strategic goods like crude oil.

Higher taxes, along with sanctions-driven rent-seeking and corruption, can drive more businesses into the informal economy. The informal sector, which is constrained by limited financial and technological resources, tends to use more emissions-intensive energy, reducing energy efficiency and increasing pollution (Biswas et al, 2012). As formal output declines and the informal economy grows, energy consumption per unit of GDP rises, further diminishing overall energy efficiency.

Figure 1. A simple framework for thinking about the impact of sanctions on energy efficiency

Hypotheses and data

We propose the following hypotheses for testing in the case of Iran:

Hypothesis 1: An increase in the sanction intensity index is linked to lower energy efficiency in industrial sub-sectors, ceteris paribus.

Hypothesis 2: An increase in the sanction intensity index has a more pronounced negative effect on energy efficiency in sectors with higher import dependence, ceteris paribus.

To test our hypotheses, we use a panel dataset covering the years 2015 to 2019, with data from 24 selected industrial sub-sectors in Iran. Our study focuses on analysing energy efficiency within these sub-sectors.

To calculate energy efficiency, data are collected from manufacturing industries with at least ten employees, based on the two-digit International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC) codes. The relevant data are obtained from the Statistical Center of Iran.

To calculate the energy efficiency scores at the industrial sub-sectors, we have used the directional distance function (DDF) and data envelopment analysis (DEA). The key explanatory variable is sanction intensity at the industrial sub-sectors.

We create an index that measures the overall impact of sanctions on industrial sub-sectors. This index combines several factors related to sanctions. We use principal component analysis to simplify these factors into a single measure. In addition to the sanctions index, we control for other variables that capture the relevant characteristics at the industrial sub-sectors for energy efficiency. Industrial sub-sectors fixed effects are also included.

Results

The findings reveal a statistically significant negative effect of sanctions on energy efficiency across Iranian industrial sub-sectors. Specifically, for every unit increase in the sanctions index (with a standard deviation of 1.47), energy efficiency in these sub-sectors declines by about 1.4%. Moreover, if the sanction intensity index shifts from low to high (an interquartile change of 2.30), energy efficiency is expected to decrease by 3.16%.

We also analyse the impact of sanctions by dividing the sample into sectors with above- and below-average import dependence. Notably, the negative effects of sanctions are significant in sectors with higher import dependence. These sectors, which rely more on international markets for their inputs and production, experience greater declines in energy efficiency due to sanctions. Specifically, a one-unit increase in the sanction intensity index correlates with a 5.6% reduction in energy efficiency for high-dependence sectors, after accounting for other variables and fixed effects.

Sanctions have led to the devaluation of the rial and increased import costs, alongside restrictions on the export of dual-use equipment and machinery. These financial sanctions also significantly raise transactions costs, adversely affecting businesses that are heavily reliant on imports. Conversely, in sectors with lower-than-average import dependence, the impact of sanctions on energy efficiency is statistically insignificant, indicating that these self-sufficient units are less affected by sanctions.

Conclusion

In this study, we develop energy efficiency scores and a sanction intensity index for industrial sub-sectors in Iran from 2015 to 2019. We demonstrate that sanctions have a negative and significant effect on energy efficiency. This effect is stronger in sub-sectors with above-average import dependence.

Further reading

Balali, H, MR Farzanegan, O Zamani and M Baniasadi (2024) ‘Economic sanctions, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in Iran: a system dynamics model’, Policy Studies 1-30.

Biswas, AK, MR Farzanegan and M Thum (2012) ‘Pollution, shadow economy and corruption: Theory and evidence’, Ecological Economics 75: 114-25.

Chen, YE, Q Fu, X Zhao, X Yuan and C-P Chang (2019) ‘International sanctions’ impact on energy efficiency in target states’, Economic Modelling 82: 21-34.

Cheratian, I, S Goltabar and MR Farzanegan (2023) ‘Firms’ persistence under sanctions: Micro-level evidence from Iran’, The World Economy 46(8): 2408-31.

Demir, F, and SS Tabrizy (2022) ‘Gendered effects of sanctions on manufacturing employment: Evidence from Iran’, Review of Development Economics 26(4): 2040-69.

Dizaji, SF (2014) ‘The effects of oil shocks on government expenditures and government revenues nexus (with an application to Iran’s sanctions)’, Economic Modelling 40: 299-313.

Dizaji, SF, and MR Farzanegan (2021) ‘Do Sanctions Constrain Military Spending of Iran?’, Defence and Peace Economics 32: 125-50.

Farzanegan, MR (2011) ‘Oil revenue shocks and government spending behavior in Iran’, Energy Economics 33(6): 1055-69.

Farzanegan, MR (2013) ‘Effects of International Financial and Energy Sanctions on Iran’s Informal Economy’, SAIS Review of International Affairs 33(1): 13-36.

Farzanegan, MR (2022) ‘The Effects of International Sanctions on Iran’s military spending: A Synthetic Control Analysis’, Defence and Peace Economics 33: 767-78.

Farzanegan, MR, and E Batmanghelidj (2023) ‘Understanding Economic Sanctions on Iran: A Survey’, The Economists’ Voice 20: 197-226.

Farzanegan, MR, and S Fischer (2021) ‘Lifting of International Sanctions and the Shadow Economy in Iran: A View from Outer Space’, Remote Sensing 13(22): 4620.

Farzanegan, MR, and B Hayo (2019) ‘Sanctions and the shadow economy: empirical evidence from Iranian provinces’, Applied Economics Letters 26(6): 501-5.

Farzanegan, MR, MM Khabbazan and H Sadeghi (2016) ‘Effects of Oil Sanctions on Iran’s Economy and Household Welfare: New Evidence from A CGE Model’, in Economic Welfare and Inequality in Iran: Developments since the Revolution edited by MR Farzanegan and P Alaedini, Palgrave Macmillan US.

Ghomi, M (2022) ‘Who is afraid of sanctions? The macroeconomic and distributional effects of the sanctions against Iran’, Economics and Politics 34(3): 395-428.

Gutmann, J, M Neuenkirch and F Neumeier (2023) ‘The economic effects of international sanctions: An event study’, Journal of Comparative Economics 51: 1214-31.

Haidar, JI (2017) ‘Sanctions and export deflection: evidence from Iran’, Economic Policy 32(90): 319-55.

Jabari, L, AA Salem, O Zamani and MR Farzanegan (2024 ‘Economic sanctions and energy efficiency: Evidence from Iranian industrial sub-sectors’, Energy Economics 139: 107920.

Laudati, D, and MH Pesaran (2023) ‘Identifying the effects of sanctions on the Iranian economy using newspaper coverage’, Journal of Applied Econometrics 38(3): 271-94.

Moghaddasi Kelishomi, A, and R Nisticò (2023) ‘Trade sanctions and informal employment’.

Torbat, AE (2005) ‘Impacts of the US Trade and Financial Sanctions on Iran’, The World Economy 28(3): 407-34.

Zamani, O, MR Farzanegan, J-P Loy and M Einian (2021) ‘The Impacts of Energy Sanctions on the Black-Market Premium: Evidence from Iran’, Economics Bulletin 41(2): 432-43.