In a nutshell

Global interlinkages play a significant role in enhancing firms’ innovation performance in developing countries; participation in global value chains is a vital channel for catching up to the fast-shifting world technological frontier.

GVC participation provides incentives for firms’ technological and auxiliary services innovation in the MENA region; medium R&D intensive sectors strengthens the positive effect of GVC participation on auxiliary services innovation.

Investing in physical and human capital is key to enhancing firms’ absorptive capacities and stimulating innovation output; fiscal policy can also play a vital role in easing the financial constraints that are obstructing firms from innovation.

Despite the rapid technological advances of the fourth industrial revolution, firms in emerging regions continue to lag behind the technological frontier (UNCTAD, 2021). But although innovation remains spatially clustered in advanced economies, foreign interlinkages provide the opportunity for the dissemination of knowledge between firms participating in global value chains (GVCs). Foreign knowledge sourcing is a key input into domestic innovation, and participation in GVCs directly stimulates that (Coe and Helpman, 1995).

Achieving greater impact of GVC participation on firms’ innovation performance will help to deliver on the ninth United Nations sustainable development goal, which aims to foster innovation and infrastructure. Equally important, revealing the moderating role of sectoral heterogeneity is necessary for GVC-driven progress on innovation in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries that are abundant in unskilled labour.

Because of several disadvantages, GVC participation is mitigated in many developing regions. In MENA, more than four-fifths of firms do not participate in GVCs. In addition, most economic activities are highly intensive in unskilled labour and low-intensive in research and development (R&D).

Yet, compared with skilled labour and medium-high R&D intensity, the innovation shares of firms engaging in unskilled labour and low R&D intensive activities indicate that the comparative advantage of the MENA region does not justify its poor innovation performance.

Research on innovation and global value chains

In recent research, we show that GVC participation by MENA firms positively affects different innovation measures (Eissa and Zaki, 2023). We distinguish between two kinds of innovation: technological innovation, which encompasses new products and services, and new production processes; and auxiliary services innovation, which relates to less substantive innovation such having a website and communicating by email.

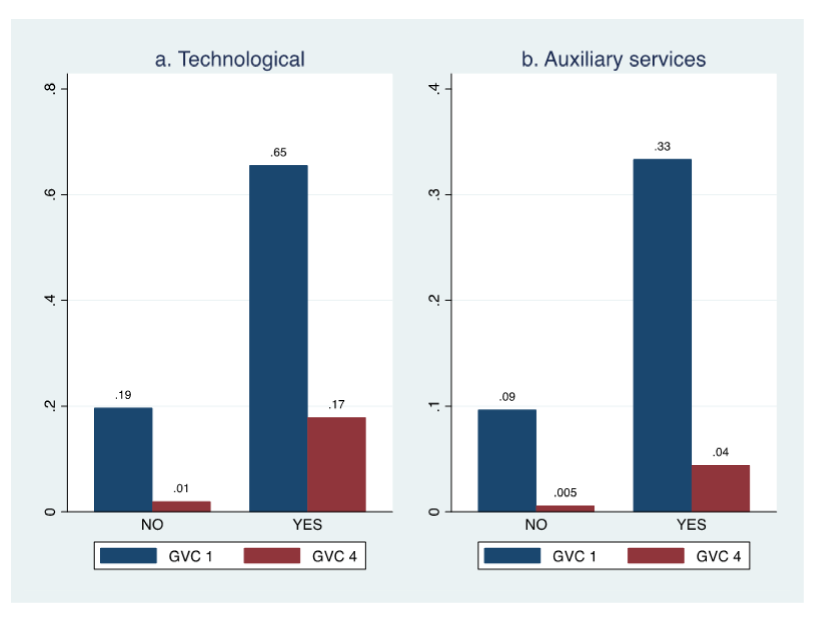

Figure 1 presents the shares of firms’ innovation against GVC participation in the MENA region. On average, along the two innovation measures, GVC-participating firms perform significantly higher than their non-GVC-participating counterparts.

Figure 1: Technological and auxiliary services innovation against GVC participation

Source: Authors’ construction based on the comprehensive WBES dataset.

Notes: GVC 1 entails that firms are engaged in exporting and importing activities. GVC 4 entails that firms are engaged in exporting and importing activities, have foreign-owned shares, and have international quality certification.

Studying the impact of GVC participation on firms’ technological and auxiliary services innovation emphasises a learning opportunity for firms in the region. In addition, since sectoral heterogeneity potentially catalyses the positive impact of GVC participation on firms’ innovation, we integrate sectoral analysis and distinguish between two factor intensities: skill level and R&D. While skilled labour directly motivates technological innovation, unskilled labour does not mitigate the GVC-positive effect.

By underlining the importance of firms’ GVC participation in realising innovation progress, we highlight that sectoral heterogeneity does not regulate the GVC impact on technological innovation in MENA countries. Put differently, sectoral heterogeneity remains neutral in catalysing the GVC-positive effect on technological innovation.

Yet, medium R&D intensive activities strengthen the GVC-positive effect on auxiliary services innovation. Given the slow progress of innovation in the region, encouraging GVC participation is a vital channel for catching up to the fast-shifting global technological frontier.

Implications for policy

From a policy standpoint, recommendations for realising greater GVC-driven innovation in the MENA region are twofold. First, ample GVC participation in the MENA region necessitates minimising underlying mitigators. Aside from controlling trade costs, a revitalised investment climate is necessary to encourage greater integration into GVCs.

Second, investing in physical and human capital is key to enhancing firms’ absorptive capacities and stimulating innovation output. Undoubtedly, R&D spending requires sufficient access to finance, which is limited in developing regions due to undeveloped financial markets.

Hence, fiscal policy can play a vital role in easing the financial constraints that are obstructing firms from innovation. For example, implementing tax incentive programmes for innovative firms can counterbalance the burden of innovation costs.

In addition, directing government spending to knowledge-intensive services and providing direct financial support to research activities can enhance domestic capabilities and facilitate the process of absorbing new technologies.

Finally, at the institutional level, providing more extensive protection of intellectual property is indispensable to initiate the virtuous circle of innovation.

Further reading

Coe, DT, and E Helpman (1995) ‘International R&D Spillovers’, European Economic Review 39(5): 859-87.

Eissa, Y, and C Zaki (2023) ‘GVC and Innovation: Evidence from MENA Firm-level Data’, ERF Working Paper No. 1672.

UNCTAD (2021) ‘Technology and Innovation Report: Catching Technological Waves, Innovation with Equity’, United Nations.