In a nutshell

New research examines the response of Saudi Arabia’s military spending to greater economic integration of Iran into global markets, via the lifting of sanctions or substantial enhancements in its political relations with neighbouring powers.

As tensions ease due to Iran's greater economic involvement on the global stage, there is a subsequent reduction in military build-up, which could potentially lessen Saudi Arabia's need to increase defence spending.

The economic globalisation of Iran may result in a significant peace dividend in the Persian Gulf, especially for Saudi Arabia, one of its biggest regional competitors.

The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and the E5+1 powers (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council – China, France, Russia, the UK and the United States – plus Germany) implemented in 2016 was short-lived. Following the election of Donald Trump, sanctions were re-imposed on Iran in 2018. But talks between Iran and Western countries persist, fostering optimism for easing regional tensions and discovering a way to lift sanctions.

This optimism grew, particularly following the renewal of diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia in early 2023 (Hafezi et al, 2023). Even though this matter has received significant attention in the media, there doesn’t seem to have been any empirical research on how Saudi Arabia may respond to the openness of the Iranian economy to globalisation.

It is still uncertain whether a more globally engaged Iran – after the lifting of economic sanctions and a diplomatic agreement with Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Cooperation Council partners – could alleviate the Saudi government’s security apprehensions and consequently lead to a decrease in its military expenditures.

A new study (Farzanegan, 2023) examines the response of Saudi Arabia’s military spending to positive global economic integration shocks in Iran.

Globalisation and military spending: a complicated tango

An earlier study (Solarin, 2018) shows that the economic globalisation of countries may reduce their military spending. After integration in the global economy, the desire to accumulate wealth through trade and economic liberalisation grows, and that raises the opportunity costs of developing or engaging in conflicts. A reduction in overall conflict may also reduce the necessity of countries to spend on military and defence (Paul and Ripsman, 2004).

What’s more, the probability of conflict between trading partners declines (Martin et al, 2008). Globalisation of countries may foster peace and stability, and reduce the need for militarisation (Kollias and Paleologou, 2017). Farzanegan (2018) shows that one of the significant determinants of military spending in the Middle East and North Africa is the risk of external conflict (which may increase following the economic isolation of countries, for example, due to sanctions).

But economic globalisation may also increase income inequality (Heimberger, 2020). Increasing inequality in a country is one of the factors that may increase the risk of internal conflict and political instability (Farzanegan and Witthuhn, 2017). Unstable political systems may result in growing regional tensions, as governments seek to shift the focus of their population away from domestic reforms towards external threats.

The latter outcome was observed in late 2022 when the Iranian government faced significant social protests under the slogan ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ (Farzanegan and Fischer, 2023). Facing large domestic protests, Iran’s government warned its neighbouring countries, including Saudi Arabia, that it would respond to any effort to destabilise the nation. Speaking about its regional adversary, Saudi Arabia, Iran’s intelligence minister mentioned that there’s no assurance that Tehran will persist with its ‘strategic patience’. He added that if Iran chooses to retaliate, the luxurious structures of these countries will collapse (Reuters, 2022).

How to examine the response of Saudi Arabia’s military spending to Iran’s economic globalisation

The analysis in the new study relates changes in a particular variable (Saudi Arabia military spending) to changes in its own lags and changes in the lags of other variables such as Iran’s economic globalisation.

As a proxy for the effect of reduced tension in Iran’s foreign relations and the possible lifting of sanctions, the study uses a positive shock to Iran’s economic globalisation index (see Gygli et al, 2019 for more detail on the index). In this study, political and social globalisation indices are also considered. While the data for the globalisation indicators for Iran are available from 1979, the estimation sample starts after the end of Iran-Iraq war because of data availability for military spending per capita and a wider dataset for Saudi Arabia.

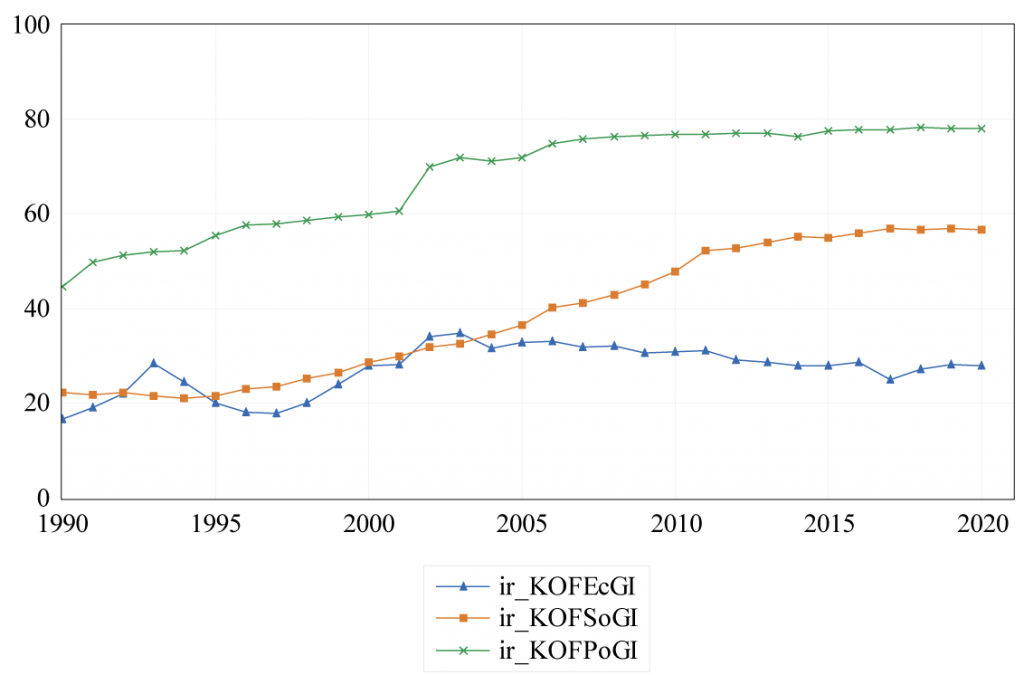

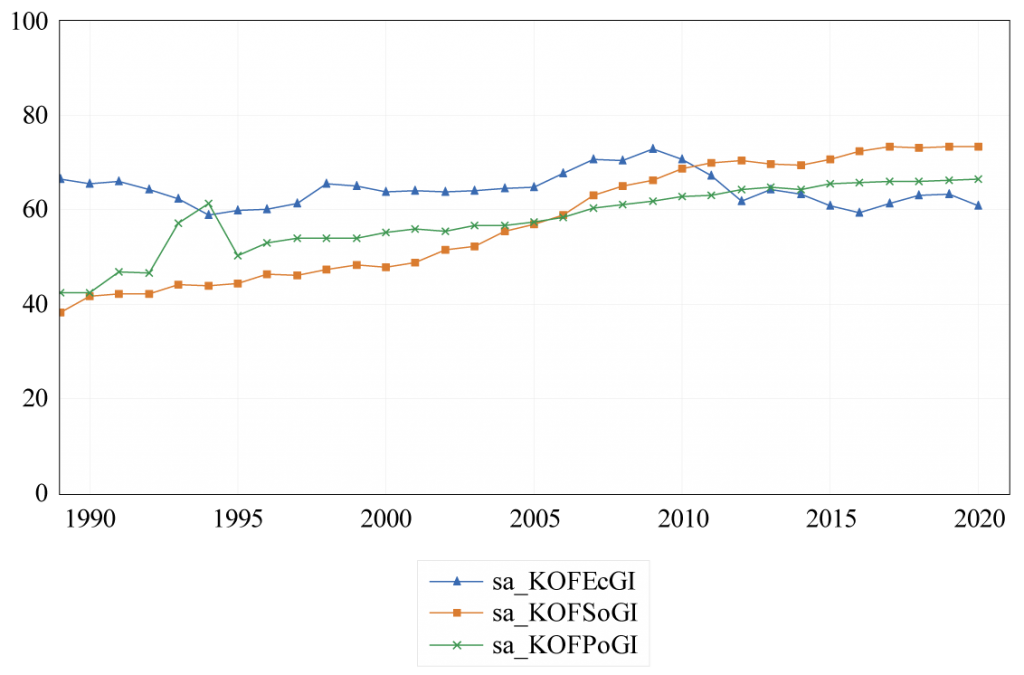

Figure 1 shows three dimensions of globalisation in Iran since 1990. The development of these indicators for Saudi Arabia is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. KOF globalisation indicators of Iran, 1990-2020

Figure 2. KOF globalisation indicators of Saudi Arabia, 1990-2020

Several factors could contribute to positive changes in Iran’s economic integration within global markets. Among these, the removal of sanctions – briefly experienced in 2016-17 – stands out as a significant driver. Following the implementation of the JCPOA in 2016, the chief executive officer of Griffon Capital, an Iran-focused asset management group, remarked, ‘The lifting of sanctions on Iran has created an unprecedented opportunity for investors. The Iranian economy boasts strong fundamentals and is anticipated to grow at an average rate of 4-6 percent annually over the next five years’ (Cosgrave, 2016).

Data on military spending are from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. In assessing Saudi Arabia’s military spending response to a positive shift in Iran’s economic globalisation, the study includes control variables, such as Saudi Arabia’s real GDP per capita and the proportion of the working-age population (15-64 years old). A rising working-age population exerts additional demands on public services such as education and healthcare, and creates increased pressure for investments in job creation and infrastructure.

These factors can influence the allocation of funds towards the military budget (Dizaji and Farzanegan, 2021). Considering that Saudi Arabia’s military expenditure might be influenced by its overall economic performance, the study includes the logarithm of real GDP per capita as a broader indicator of economic performance, also including the evolution of its oil export revenues. Data for the working-age population and GDP per capita are sourced from the World Bank (2023).

Findings

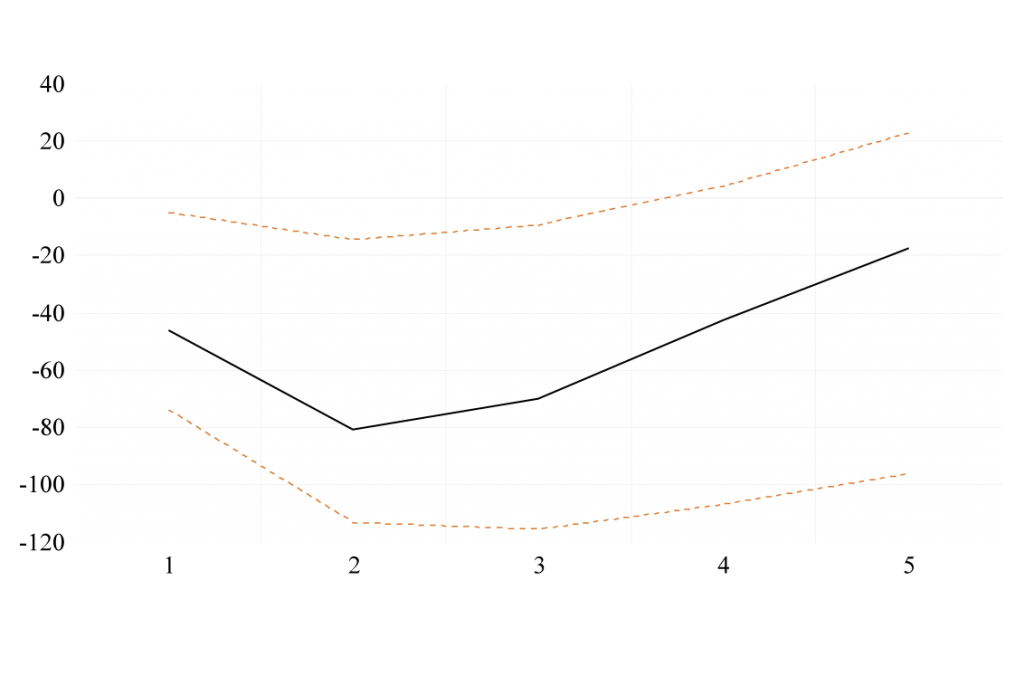

The main result is shown in Figure 3, indicating the response of Saudi Arabia military spending per capita to a one standard deviation positive shock in the economic globalisation index of Iran. The results are obtained after controlling for the share of Saudi Arabia’s working age population and Saudi GDP per capita.

The response of Saudi Arabia’s military spending to Iran’s integration into the global economy is negative and statistically significant during the first three years after the initial shock. Any sudden changes leading to increased economic ties between Iran and the global economy –such as the lifting of sanctions or substantial enhancements in Iran’s political relations with neighbouring powers – could potentially lessen Saudi Arabia’s necessity to increase military spending. This is because Iran is one of Saudi Arabia’s significant regional competitors.

Both positive shocks to the trade and financial globalisation of Iran results in decreasing response of military spending in Saudi Arabia. But the response of Saudi military spending to a positive shock in Iran’s social globalisation index is positive. Iran’s economic integration might raise the stakes, potentially reducing incentives for conflict due to higher economic risks involved.

But concerning social and cultural globalisation, Saudi Arabia perceives Iran’s social elements as a growing security concern. This perception might stem from the belief that Iran aims to exert influence on Shia populations near Saudi Arabia, spanning countries like Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. As this study primarily centres on economic globalisation, further exploration into how other dimensions of globalisation, especially social and cultural aspects, affect Saudi Arabia’s security perceptions should be pursued in future research.

Figure 3. The response of Saudi Arabia’s per capita military spending (US$) to a generalised one standard deviation positive shock in Iran’s economic globalisation index

Note: The solid line traces the response over the period following the shock. The dashed lines represent 68% confidence intervals. The horizontal axis shows the years following the initial positive shock in Iran’s economic globalisation index.

Conclusion

One possible explanation for the result of this research is the increased financial burdens linked to conflicts and tensions that emerge when a country actively engages in the global economy. As tensions ease due to Iran’s economic involvement on the global stage, there is a subsequent reduction in military build-up, especially in the Persian Gulf and notably by Saudi Arabia.

Further reading

Cosgrave, Jenny (2016) ‘Iran opens doors to investors with latest fund launch’, Yahoo Finance.

Dizaji, Sajjad Faraji, and Mohammad Reza Farzanegan (2021) ‘Do Sanctions Constrain Military Spending of Iran?’, Defence and Peace Economics 32(2): 125-50.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza (2018) ‘The Impact of Oil Rents on Military Spending in the GCC Region: Does Corruption Matter?’, Journal of Arabian Studies 8(sup1): 87-109.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza (2023) ‘What Is the Potential Impact of Iran’s Economic Global Integration on Saudi Arabia’s Military Spending?’, Defence and Peace Economics 0(0): 1-19.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza, and Sven Fischer (2023) ‘The Effect of the “Woman Life Freedom” Protests on Life Satisfaction in Iran: Evidence from Survey Data’, CESifo Working Paper 10643.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza, and Stefan Witthuhn (2017) ‘Corruption and Political Stability: Does the Youth Bulge Matter?’, European Journal of Political Economy 49: 47-70.

Gygli, Savina, Florian Haelg, Niklas Potrafke and Jan-Egbert Sturm (2019) ‘The KOF Globalisation Index – Revisited’, Review of International Organizations 14(3): 543-74.

Hafezi, Parisa, Nayera Abdallah and Aziz El Yaakoubi (2023) ‘Iran and Saudi Arabia Agree to Resume Ties in Talks Brokered by China’, Reuters.

Heimberger, Philipp (2020) ‘Does Economic Globalisation Affect Income Inequality? A Meta-Analysis’, The World Economy 43(11): 2960-82.

Kollias, Christos, and Suzanna-Maria Paleologou (2017) ‘The Globalization and Peace Nexus: Findings Using Two Composite Indices’, Social Indicators Research 131(3): 871-85.

Martin, Philippe, Thierry Mayer and Mathias Thoenig (2008) ‘Make Trade Not War?’, Review of Economic Studies 75(3): 865-900.

Paul, TV, and Norrin Ripsman (2004) ‘Under Pressure? Globalisation and the National Security State’, Millennium 33(2): 355-80.

Reuters (2022) ‘Iran Warns Saudi Arabia ‘our Strategic Patience’ May Run out – Fars’.

Solarin, Sakiru Adebola (2018) ‘Determinants of Military Expenditure and the Role of Globalisation in a Cross-Country Analysis’, Defence and Peace Economics 29(7): 853-70.

World Bank (2023) ‘World Development Indicators’.