In a nutshell

The average rates of labour force participation among women of all ages in GCC countries are less than half the rates for men; over the period 2007-17, the average female youth unemployment rate was more than quadruple the average male youth unemployment rate.

Empirical evidence indicates that greater labour market flexibility reduces the female youth unemployment rate; perhaps surprisingly, the social contract, as measured by the compensation that government employees receive, has the same effect.

Labour market flexibility is essential for reducing the female youth unemployment rate in GCC countries, while the social contract is not.

Over the period from 2007 to 2017, the average unemployment rate among young women in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was more than quadruple the average unemployment rate among young men. Would more flexible labour markets reduce the female youth unemployment rate? And does the generous GCC social contract demotivate nationals from employment? New research addresses these questions empirically and provides answers (Mina, 2023a; 2023b).

The high-income countries of the GCC – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – have long relied substantially on foreign labour, thanks to the windfall of oil revenues that began in the early 1970s.

GCC governments have shared these revenues with their populations in the form of highly paid government and public sector jobs, free access to public services, such as education and health, subsidised utilities and generous pensions at retirement (World Economic Forum, 2014; Assidmi and Wolgamuth, 2017).

In turn, citizens have supported their government. The exchange of benefits and support is the essence of social contracts.

The GCC countries’ reliance on foreign labour has not had a significant impact on the skills, productivity and wellbeing of native workers because of labour market segmentation. One segment is the national labour force, members of which typically hold protected government jobs, while the other segment is foreign labour, workers who typically hold low-paid private sector jobs.

In the national labour segment, wages are determined by the government, and hiring and firing is not easy. In the foreign labour segment, in contrast, wages are negotiable, and hiring and firing is easy.

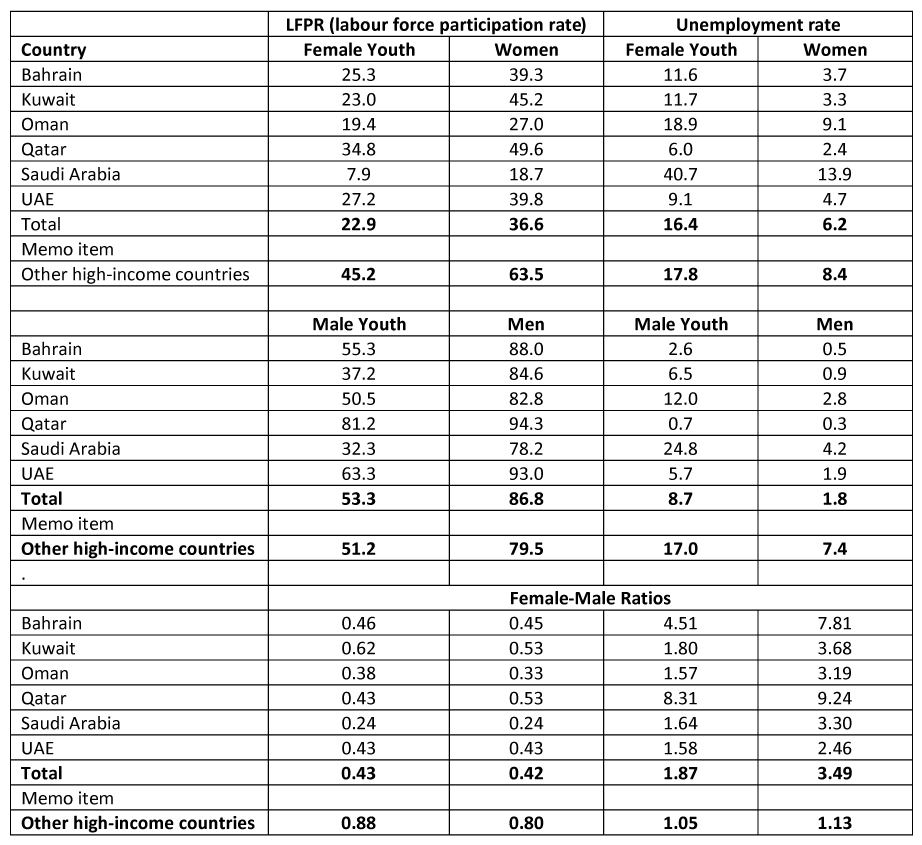

Despite the influx of relatively cheap foreign labour, the GCC countries have enjoyed lower youth unemployment rate compared with other high-income countries. Over the period from 1990 to 2020, the average male youth and male unemployment rates in the GCC countries were 8.7% and 1.8% respectively, as Table 1 shows. In other high-income countries, these rates were much higher, at 17% and 7.4% respectively.

Over the same period, the female youth and female unemployment rates in the GCC countries were 16.4% and 6.2% respectively. In other high-income countries, these rates were slightly higher, at 17.8% and 8.4% respectively.

Table 1: GCC labour statistics (1990-2020 period average)

Source: Mina (2023a).

In addition to cultural factors, the decision of women in GCC countries to participate in the labour force and search for jobs is influenced by the social contract. The World Economic Forum (2014) notes that ‘the social contract has led to low labour force participation rates among GCC nationals… and a high proportion of non-working dependents per employed person’. The average labour force participation rates (LFPR) for female youth and women were less than half the rates for male youth and men, as Table 1 shows.

Against a backdrop of significant reliance on foreign labour, labour market segmentation, oil revenues that continue to finance a generous social contract and protect national labour, and high ratios of female-male youth unemployment rates, Mina (2023a; 2023b) investigates the extent to which flexible labour markets, in the presence of a generous social contract, reduce the female youth unemployment rate in GCC countries.

The new research hypothesises that labour market flexibility reduces the female youth unemployment rate. Many empirical studies support the relationship that flexible labour markets reduce unemployment rates. These include Phelps (1994), Layard and Nickell (1986) and Layard et al (1991), Nickell (1997), Broer et al (2000), Bassanini and Duval (2009), Bernal-Verdugo et al (2012), and Mursa et al (2018).

Mina also hypothesises that the generous social contract increases the female youth unemployment rate. The theory that underlies this hypothesis is the income effect, which in essence suggests that higher incomes provide an incentive for workers to reduce their working hours.

The income effect assumes that workers have jobs. In the case of workers being unemployed, the income effect can reduce the incentive for job search in GCC countries through unemployment benefits, free education and health services, child support allowances, and subsidised goods and services. As a result, frictional unemployment increases.

The empirical evidence in the new study shows that labour market flexibility reduces the female youth unemployment rate in GCC countries, as expected. But contrary to the second hypothesis, the evidence shows that the social contract, measured by the compensation that government employees receive, also reduces the female youth unemployment rate.

The social contract is primarily intended to garner political support for the government. By reducing female youth unemployment, the social contract benefits the GCC countries not only politically but also economically and socially.

Can the GCC countries continue to rely on the social contract to reduce female youth unemployment rates? Mina (2023a) shows that labour market flexibility is essential for reducing the female youth unemployment rate, while the social contract is not.

This novel research has important policy implications for selecting the appropriate tool to address female youth unemployment. As the empirical evidence suggests, labour market flexibility should be the policy of choice for addressing female youth unemployment.

Further reading

Assidmi, LM, and E Wolgamuth (2017) ‘Uncovering the Dynamics of the Saudi Youth Unemployment Crisis’, Systemic Practice and Action Research 30(2): 173-86.

Bassanini A, and R Duval (2009) ‘Unemployment, Institutions, and Reform Complementarities: Reassessing the Aggregate Evidence for OECD Countries’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25(1): 40-59.

Bernal-Verdugo, L, D Furceri and D Guillaume (2012) ‘Labor Market Flexibility and Unemployment: New Empirical Evidence of Static and Dynamic Effects’, Comparative Economic Studies 54(2): 251-73.

Broer, DP, DAG Draper and FH Huizinga (2000) ‘The Equilibrium Rate of Unemployment in the Netherlands’, De Economist 148(3): 345-71.

Layard, R, and S Nickell (1986) ‘Unemployment in Britain’, Economica 53: S121-69.

Layard, R, S Nickell and R Jackman (1991) Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford University Press.

Mina, W (2023a) ‘Do Labor Markets and the Social Contract Increase Female Youth Unemployment in the GCC Countries?’, Middle East Development Journal 15(1): 130-50.

Mina, W (2023b) ‘Female Youth Unemployment in the GCC Countries’, Qeios.

Mursa, GC, A-O Iacobuţǎ and M Zanet (2018) ‘An EU Level Analysis of Several Youth Unemployment Related Factors’ Studies in Business and Economics 13(3): 105-17.

Nickell, S (1997) ‘Unemployment and Labor Market Rigidities: Europe versus North America’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 11(3): 55-74.

Phelps, ES (1994) Structural Slumps: The Modern Equilibrium Theory of Unemployment, Interest, and Assets, Harvard University Press.

World Economic Forum (2014) Rethinking Arab Employment: A Systemic Approach for Resource-Endowed Economies.