In a nutshell

There are several lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic for effective risk communication and management during public health emergencies to encourage appropriate public health behaviours; first and foremost, it is crucial to prioritise efforts to enhance public attitudes and knowledge.

Establishing trust in government authorities is essential: by fostering trust, the perception of risk can be influenced, thereby promoting the adoption of preventive public health measures such as mask wearing, social distancing and handwashing.

Some measures of social protection implemented by MENA governments during the pandemic created a dilemma, forcing individuals, particularly those in lower income groups, to choose between complying with the required preventive actions and maintaining a source of income.

The outbreak of Covid-19 presented formidable challenges for healthcare systems across the Middle East and North Africa. From February 2020 to February 2023, MENA countries reported over 26 million confirmed cases and more than 300,000 deaths (WHO, 2023).

The widespread transmission of the virus in the region can be attributed to a combination of institutional and contextual factors. These include the lack of preparedness within healthcare systems, insufficient availability of health resources and management strategies, initial government dismissals of the seriousness of the infection, and the presence of continuing conflicts, which collectively hampered individuals’ access to healthcare services (Abu Hatab et al, 2023).

But how did people react once the disease arrived? Risk perception plays a crucial role in shaping people’s health behaviours. The degree to which they perceive Covid-19 infection as severe (and likely to affect their health) influences how they act in terms of compliance with risk prevention and mitigation measures (such as wearing face masks, practicing social distancing and maintaining regular handwashing).

In terms of behavioural theory, risk perception serves as a predictor for the maintenance of such behaviours (Weinstein, 1993). So, it is essential for policy-makers to gain a deeper understanding of how people’s perception of the severity and their susceptibility to threats influence their behavioural responses and compliance with government-mandated mitigation measures in times of public health crises. This understanding is crucial for formulating effective public health strategies aimed at reducing risks.

Despite an extensive body of research on risk perception and preventive behaviours individually, there is a noticeable research gap in the MENA region regarding the association between the two. Consequently, there is limited understanding of how people’s level of perception influences their subsequent engagement in preventive behaviours.

To address this gap, a new study builds on the Health Belief Model (HBM) – developed by Rosenstock (1974) and validated through empirical studies (Carpenter, 2010). The new investigation examines the association between people’s concern about contracting Covid-19 and their adoption of three preventive behaviours: wearing face masks, practicing social distancing and handwashing.

The authors use a panel dataset consisting of 34,219 observations from five MENA countries: Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia. The empirical model controls for various factors including country and survey-wave fixed effects, socio-demographic characteristics (such as gender, age, income and education level) and community characteristics (by differentiating between rural and urban areas).

What does the research reveal about risk and behaviour?

Past evidence shows that health-related behaviours are linked closely to a person’s level of concern and anxiety regarding perceived risks or threats. People are more likely to engage in proactive behaviours if they believe the given behaviour will indeed make them safer, and that adopting the behaviour won’t be prohibitively hard or inconvenient.

Within the analytical frameworks of the HBM, risk prevention or reduction behaviours are influenced by individuals’ perceptions, including their level of concern, perceived severity and susceptibility. In addition to this, a set of modifying factors such as demographic characteristics, health-related habits and knowledge can also influence a person’s level of compliance.

In the new study, compliance with Covid-19 preventive measures (wearing face masks, practicing social distancing and handwashing) is modelled as a function of infection worries, socio-economic and demographic factors, time invariance factors, and country- and administrative-level fixed effects (Amuakwa-Mensah et al, 2021).

The analysis uses data from five waves of the Combined Covid-19 MENA Monitor Household survey (CCMMHH), conducted by the ERF between November 2020 and August 2021. For further details about the methodology and dataset, see Abu Hatab et al (2023).

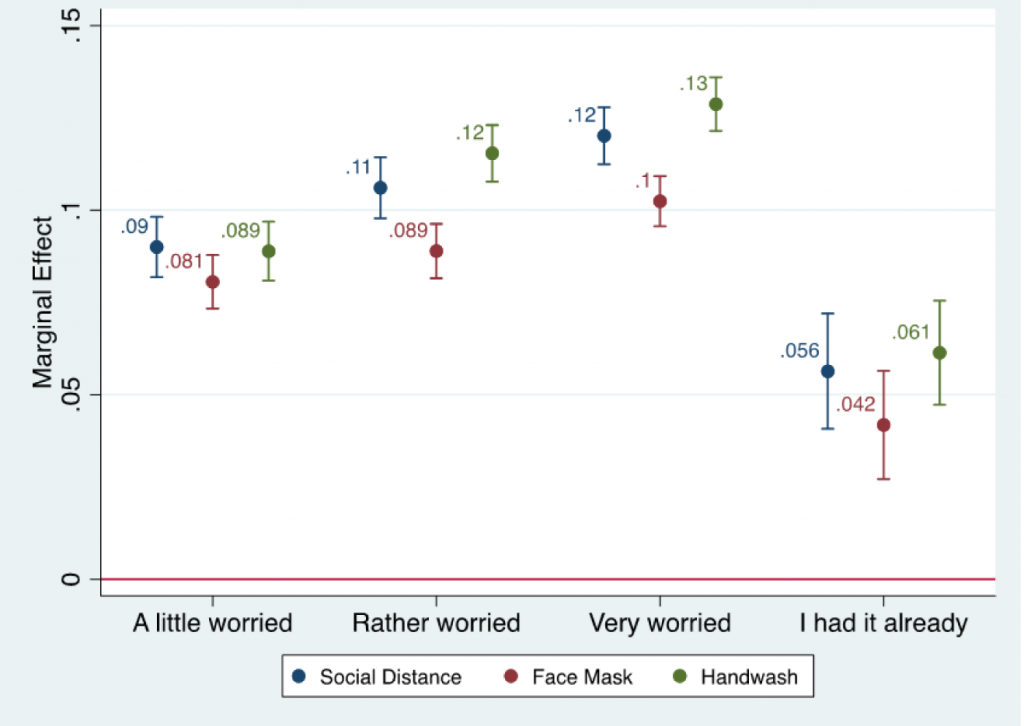

Figure 1: Marginal effect of individuals’ worriedness about Covid-19 infection on compliance with mitigation measures

The findings provide compelling evidence of the impact of risk perception on individuals’ risk-related behaviour. Adherence to Covid-19 mitigation measures exhibits an inverted U-shaped trend. Specifically, compliance with the three mitigation measures initially increased, as people’s level of concern about infection escalated from being ‘a little worried’ to ‘very worried’. Compliance then subsequently decreased after individuals contracted the virus.

The study also identifies several individual and household characteristics as important determinants of compliance with public health measures. Women are more likely to comply with the three mitigation measures compared with their male counterparts. Age was also a contributing factor, with older people more likely to adopt protective behaviours.

Educational attainment plays a significant role, with individuals holding higher educational degrees being more likely to wear face masks and practice repeated handwashing during the pandemic. Household income also has an influence, with people in the third- and fourth-income quantiles more likely to comply with the three mitigation measures, compared with those in lower income quantiles.

Adherence to mitigation measures is also negatively associated with household size. So, larger households are less likely to play by the rules. In contrast, there is no evidence of an impact from the characteristics of the community (rural versus urban areas) in which an individual resides.

There are notable differences between the surveyed countries regarding the association between concern about infection and public compliance with implemented preventive measures. The strongest association is in Tunisia and Sudan, while the lowest association is in Jordan and Morocco. It is worth mentioning that, with the exception of Morocco, the results confirm the inverted U-shaped trend of compliance odds with Covid-19 mitigation measures.

The way forward

There are several factors that affect people’s adherence to policies during times of crisis. These empirical findings provide plausible evidence about community practices around the use of risk prevention and mitigation measures during public health crises in settings with different infection incidences and response policies.

These results should be used to inform policies that aim to mitigate the transmission of infectious diseases and combat their wider negative effects. Four policy implications can be drawn from the study for effective risk communication and management during public health emergencies to encourage appropriate public health behaviours.

First and foremost, it is crucial to prioritise efforts to enhance public attitudes and knowledge. This can be achieved by guiding people towards reliable and trustworthy sources of information about the causes of infection and associated health risks. This should help to prevent the detrimental consequences of conspiracy theories that may arise during public health crises.

In this regard, establishing trust in government authorities (especially in the MENA region) is essential. By fostering trust, the perception of risk can be influenced, thereby promoting the adoption of preventive public health measures such as mask wearing.

Second, changes in risk perception over time should not be overlooked. The declining association between fear of Covid-19 infection and compliance with public health measures after someone contracts the virus raises concerns about the effectiveness of social protection measures implemented by MENA governments.

It appears that these measures created a dilemma, forcing individuals to choose between complying with preventive measures and maintaining a source of income. This has led to reduced acceptance of the implemented measures, particularly among lower-income individuals and marginalised groups in the population.

So, risk mitigation interventions and communication approaches need to shift from emergency-oriented and uncertain contexts to ones that encourage sustainable and habitual behaviours. Government interventions should consider the broader impacts of disease control measures beyond biomedical risks, by addressing the social and economic effects on the population over time. These effects can act as deterrents to public compliance with risk prevention and mitigation measures.

Third, gaining a deeper understanding of perceptions and attitudes towards mitigation behaviours and their underlying drivers among different socio-demographic groups is crucial. More efforts are needed to identify communication preferences, trusted sources and channels of information in order to design tailored interventions for each target group.

This requires mapping the key trusted influencers for each group and involving them in crafting customised communication and nudging messages, ensuring that desired behavioural changes are achieved effectively. Such strategies are more likely to succeed if they are developed through community-centred approaches that acknowledge local realities and engage meaningfully with the target groups in identifying and implementing locally appropriate mitigation measures.

Fourth and finally, the regional variation observed among the surveyed countries presents an opportunity for regional cooperation and collaboration between policy-makers in the public health sectors of these countries. MENA policy-makers can leverage these heterogeneities to develop cross-government approaches and create platforms for ongoing dialogue among stakeholders.

Such schemes should promote the sharing of experiences, effective approaches and best practices to reinforce public acceptance and willingness to adhere to preventive and mitigation measures. Cross-border challenges like Covid-19 require cooperation across borders.

Understanding the variation in underlying factors that affect both risk perception and behaviour is crucial for building resilience to future crises in the MENA region. While undoubtedly a disaster, there are useful lessons to be drawn from the pandemic. Policy-makers in the MENA region must not overlook this opportunity to learn.

Further reading

Abu Hatab, A, L Krautscheid and F Amuakwa-Mensah F (2023) ‘COVID-19 risk perception and public compliance with preventive measures: Evidence from a multi-wave household survey in the MENA region’, PLoS ONE 18(7): e0283412.

Amuakwa-Mensah, F, RA Klege, PK Adom and G Köhlin (2021) ‘COVID-19 and handwashing: Implications for water use in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Water Resources and Economics 36: 100189.

Carpenter, CJ (2010) ‘A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior’, Health Communication 25(8): 661-69.

Rosenstock, IM (1974) ‘Historical origins of the health belief model’, Health Education Monographs 2(4): 328-35.

Sulat, JS, YS Prabandari, R Sanusi, ED Hapsari and B Santoso (2018) ‘The validity of health belief model variables in predicting behavioral change: A scoping review’, Health Education 118(6): 499-512.

Weinstein, ND (1993) ‘Testing four competing theories of health-protective behavior’, Health Psychology 12(4): 324-33.

WHO (2023) WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard.