In a nutshell

Growth of firms in both the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors of the MENA region is highly dependent on international trade with non-MENA countries; the positive growth impact of participation in global value chains is particularly striking.

Exporting intermediate products to the GCC and non-MENA countries boosts growth for the region’s manufacturing sector; expanding forward global value chain participation with China and other developing countries enhances the region’s services sector.

All industries in the region stand to gain from an increase in backward global value chain participation with the EU and the United States; the regions’ firms depend on trade being at the heart of policy-makers’ economic strategies.

Over the past three decades, trade liberalisation has generally increased around the world. This has come alongside falling transport costs and enhancements in information and telecommunication technologies. The Middle East and North Africa has experienced these changes through different bilateral and regional trade agreements with countries both within and outside the region (Miniesy et al, 2004).

But integration of the MENA region into the global production system is comparatively weak, which may be due to insufficient implementation of these agreements and collaborations (Saidi and Prasad, 2018). This suggests that the benefits from trade are not yet being fully realised.

The MENA region and international trade

A recent study (Tat et al, 2023) examines past trade patterns of the region, analysing the impact of changing trade on growth in different sectors. The authors first investigate the trade patterns – that is, the backward and forward integration of the MENA region – by considering different trading partners: North Africa, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the rest of the Middle East, the European Union (EU), the United States, China, other developed countries and other developing countries.

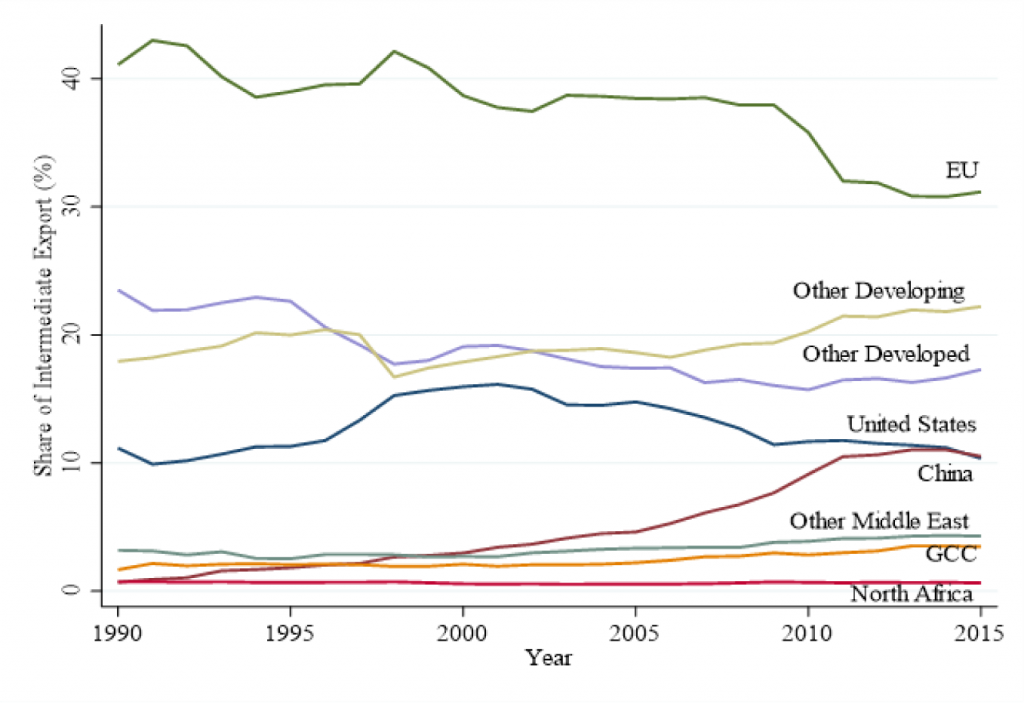

Figure 1 illustrates the shares of each country group or countries within the MENA region’s intermediate exports over 25 years from 1990. The data show that while the shares of intermediate exports to China and other developing countries increase throughout the period, the shares of intermediate exports to the EU and other developed countries decrease.

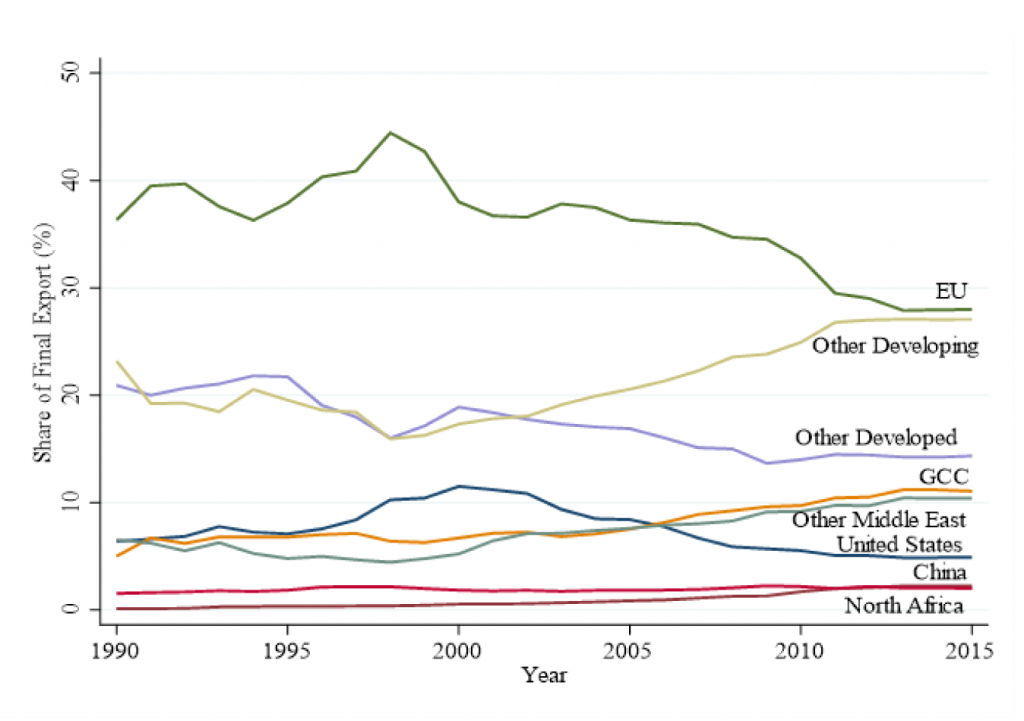

Figure 2 demonstrates the shares of each country group or country within the MENA region’s final exports. The data show that while the shares of final exports to the GCC, other Middle East and other developing countries expand throughout the period, the shares of final exports to the EU, the United States and other developed countries decrease.

Figure 1: Shares of intermediate exports (%) from the MENA by country groups

Source: Tat et al (2023)

Figure 2: Shares of final exports (%) from the MENA by country groups

Source: Tat et al (2023)

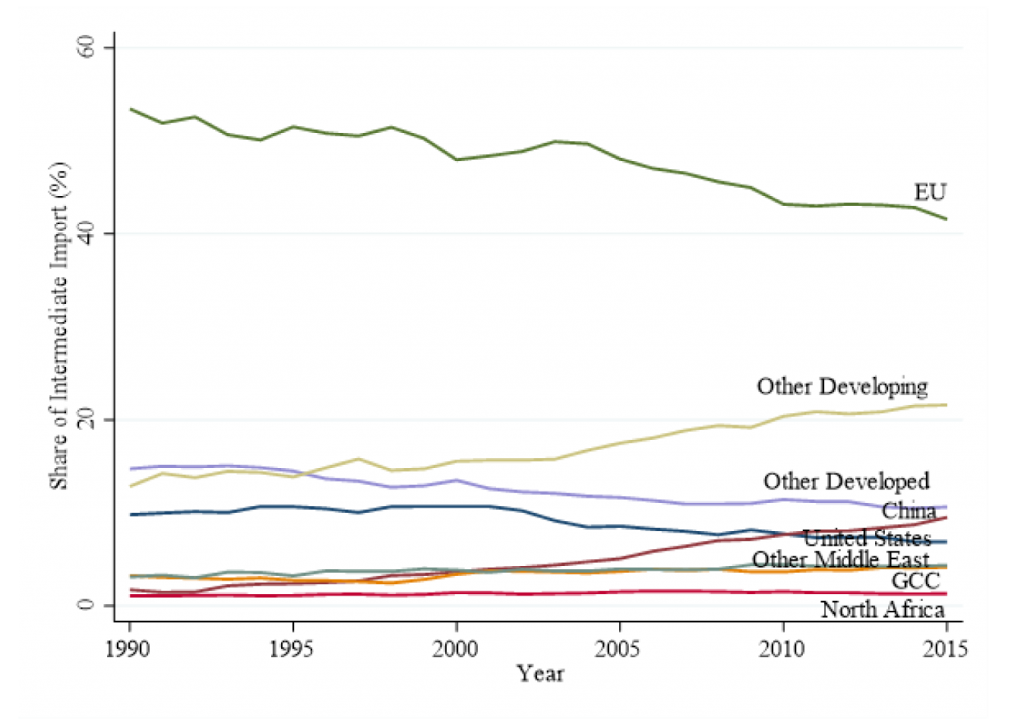

Figure 3 presents the shares of each country group or countries within the MENA regions’ intermediate imports. The data show that while the shares of intermediate imports from China and other developing countries grow throughout the period, the shares of intermediate imports from the EU, the United States and other developed countries decrease.

Figure 3: Share of intermediate imports (%) to the MENA by country groups

Source: Tat et al (2023)

Overall, the EU appears to be the main trade partner of the MENA region (over 30% of commerce), regardless of the types of trade flows. For all types of exchange, trade with other developing and developed countries reaches substantial shares. For final exports, intra-regional trade has a crucial share in the MENA region.

When considering the composition of trade according to trade partners over the period, it is apparent that while the shares of the EU and other developed countries in all types of trade tend to decrease, the shares of other developing countries in all kinds of trade, and the share of China in intermediate trade, tend to increase.

How do the growth effects of trade vary?

The study also analyses the growth impacts of trade with these country groups or countries for the manufacturing, services, agriculture and mining sectors, from 1990 to 2015. The findings reveal the importance of the positive growth impact of participation in global value chains.

Shipping goods abroad is beneficial for many businesses in the MENA region. Exporting intermediate products to the GCC, the EU, the United States, China, other developed and other developing countries boosts growth for the manufacturing sector. Intra-MENA trade of final products also seems to help businesses in the manufacturing sector grow.

In terms of buying items in, importing intermediate products from developed countries including the EU and the United States enhances growth of the manufacturing, services, agriculture and mining sectors in the MENA region. So, international trade linkages are valuable in many cases.

While exporting intermediate services to the GCC, China and other developing countries increases services sector growth, exporting final services to China and other developed countries increases overall growth. So, depending on the trade partner, different types of exchange have differing effects on firms within the MENA region.

Overall, these findings suggest that while expanding forward global value chain participation with all groups or countries promotes the MENA regions’ manufacturing sector, expanding forward global value chain participation with China and other developing countries enhances the services sector.

All industries gain from an increase in backward global value chain participation with the EU and the United States. In both cases, international trade – and the patterns of exchange – should remain at the heart of policy-makers’ economic strategies. The regions’ firms depend on it.

Further reading

Miniesy, RS, JB Nugent and TM Yousef (2004) ‘Intra-regional trade integration in the Middle East: Past performance and future potential’, in Trade Policy and Economic Integration in the Middle East and North Africa: Economic Boundaries in Flux.

Saidi, N, and A Prasad (2018) ‘Trends in trade and investment policies in the MENA region’, MENA-OECD Working Group on Investment and Trade.

Tat, Pınar, Abdullah Altun and Halit Yanıkkaya (2023) ‘The Past and the Future Trade Patterns of the MENA Region: The Pursuit of Growth’, ERF Working Paper No. 1650.