In a nutshell

Several highly indebted MENA nations find themselves in the path of debt difficulties. This situation is created by internal inefficiencies, poor governance, and a difficult global economy.

It is likely that debt burdens in several MENA countries become unsustainable, requiring restructurings that could be difficult and protracted. These risks could be mitigated through a combination of growth-boosting policies and some fiscal consolidation. However, the prospects for now appear grim.

Some form of debt restructuring may be unavoidable in high-debt countries. Debt restructurings could be very disruptive and should be seen as a last resort. But if they are inevitable, it is preferable to do them preemptively, as part of a broader set of corrective actions.

Parts of the Middle East and North Africa stand at the brink of a debt crisis

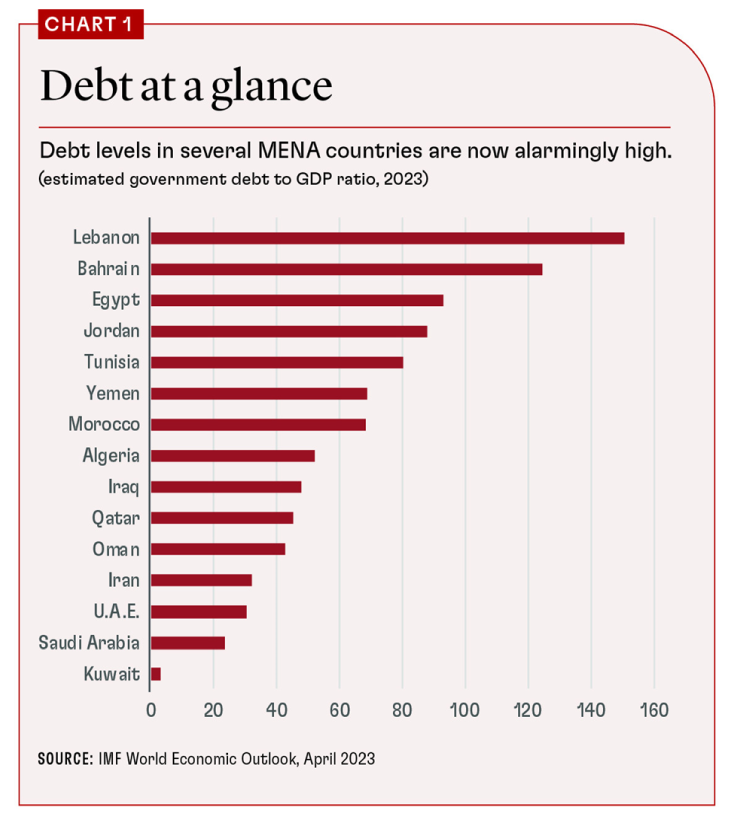

There is a debt storm brewing in parts of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Debt across the region has been climbing, reaching very high levels in several countries (Chart 1). Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia are in a precarious situation, their economic stability teetering as they grapple with the prospects of a debt crisis. Lebanon, already reeling from one of the worst economic crises in the world, is a cautionary tale. Its plunge into default has thrown a harsh spotlight on these countries’ acute debt-related challenges and their broader ramifications.

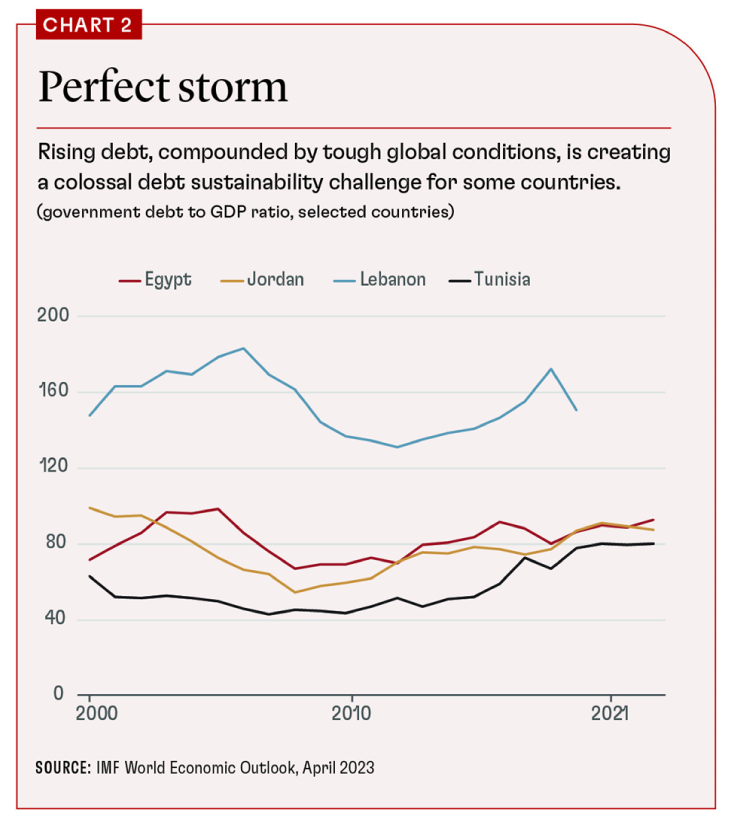

The rising tide of debt, coupled with tough global economic prospects, is stirring up a perfect storm (Chart 2). This crisis has been fueled by scarcer low-interest financing and the affluent MENA oil producers’ reluctance to continue the unconditional financial support of the past. Exacerbating this complex equation are the difficult social conditions these countries face, leaving little room for significant fiscal consolidation. Consequently, maintaining debt sustainability is a colossal challenge for these countries, and it is growing ever more daunting.

At risk are not just the prospects for economic growth but also the sociopolitical stability of these countries. The stakes are high. Amid these grim realities lies a narrow path to salvation—but that path requires bold, proactive measures to address the debt crisis head-on.

Crisis origins

The MENA region’s ballooning debt problems are deeply rooted in a blend of misfortune and poor policy decisions. Each nation—Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia—faces a unique set of problems, marked by differing political and economic landscapes, as well as disparity in the composition of their outstanding debt. Yet there is a common thread in their predicaments.

These nations have been hamstrung by persistent structural issues related to governance and regulatory frameworks, state-controlled economies, bloated public sectors that stifle private sector growth, low domestic revenue mobilization, and poorly targeted subsidies. These problems are long-standing, mainly because of inadequate reforms. Their reliance on fixed exchange rates and debt financing also contributes to a crisis in the making. The situation has been exacerbated by global economic fluctuations and recent shocks—such as the pandemic and the spillovers from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and by higher food prices, which contribute to soaring debt levels. Societal challenges and distrust in government that thwart the equitable distribution of economic adjustment burdens have compounded the problem. As a result, public debt has been exploited as a temporary stop-gap solution to delay dealing with economic problems—but without durable solutions.

Let us consider the specifics:

Egypt has endured years of economic stagnation, attributable in part to the military’s pervasive control over the economy. The pandemic’s toll on tourism, along with surging food import costs in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine, have added to Egypt’s woes. Persistent budget deficits and upholding a fixed exchange rate have resulted in substantial financing needs, met partly through short-term capital inflows. As noted in the IMF’s April 2023 Fiscal Monitor, Egypt’s gross financing needs in 2023 amount to a staggering 35 percent of its GDP, leaving it highly susceptible to interest rate hikes and rollover risks.

Jordan, too, has been grappling with low growth, resulting in part from an overvalued fixed exchange rate, along with geopolitical and economic disruptions. The large influx of Syrian refugees and trade disturbances following the Syrian civil war have further strained its economy. Meanwhile, Jordan has been wrestling with control of its public finances, burdened by hefty subsidies, public enterprise transfers, and security expenditures—largely because of geopolitical factors—all while depending heavily on official aid. Fortunately, Jordan has a more effective policymaking framework than the other three countries and is performing well under its current IMF program. Nevertheless, its high debt makes it very vulnerable to adverse developments.

Lebanon’s debt crisis was driven by an unsustainable system built on fixed exchange rates and weak public finances, which required high interest rates to draw foreign inflows—a classic Ponzi scheme. This flawed system, along with persistent political deadlock and the banking sector’s undue influence on policymaking, has precipitated a multifaceted economic and social crisis, leading to default on domestic and external sovereign debt.

Tunisia stands out as the only Arab Spring nation that appeared to take steps toward enhanced democracy and governance. However, the increasing role of the government as an employment and subsidy provider, coupled with the COVID-19 shock—which assailed the economy and budget (Mazarei and Loungani 2023)—have put Tunisia on shaky ground. The authorities insisted on maintaining exchange rate stability even when it was unaffordable. This led to dependence on external inflows, primarily from official creditors who supported Tunisia’s democratic transition. But recent political upheavals that have undermined Tunisia’s democratic progress, coupled with a refusal to implement necessary reforms, have eroded Tunisia’s debt repayment capabilities, leading the country inexorably toward debt distress.

Previous debt crises

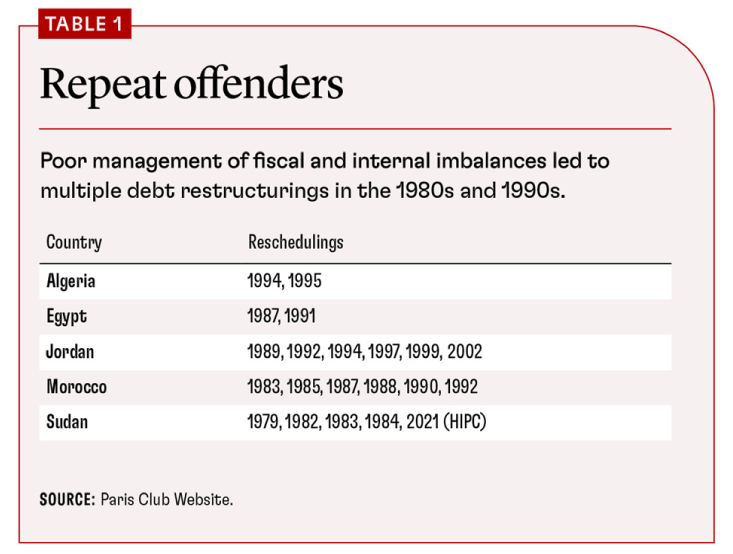

The MENA region’s tryst with debt crises is not a recent phenomenon. The region witnessed episodes of debt distress during the 1980s and 1990s, spurred by internal and international conflicts and unfavorable global conditions, including adverse shifts in commodity prices. Poor management of fiscal and external imbalances led to multiple instances of restructuring of debt that was primarily public and publicly guaranteed (see table).

The main creditors to the MENA countries during these crises were the Paris Club and regional bilateral creditors, commercial banks, and multilateral agencies. The debt crises of the 1980s were managed through agreements within the Paris Club and private banks (known as “Brady deals”), requiring structural adjustment programs.

Another series of debt rescheduling efforts took place during the 1990s and early 2000s to address debt distress caused in part by fallout from regional conflicts, notably the first Gulf War. These debt rescheduling efforts, particularly for Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan, were carried out with substantial support from the international community and international financial institutions.

Despite these historical debt restructuring episodes, today the road to further restructuring is riddled with challenges. Given the current economic climate, it is likely to be significantly more complex and difficult.

The new debt reality

Recent years have seen significant advancements in the global debt architecture, most notably the introduction of collective action clauses in sovereign bond contracts. These changes have hastened debt restructuring of sovereign Eurobonds, a step in the right direction. However, on the whole, new developments have complicated sovereign debt restructuring—and this complexity is accentuated by flaws in the global financial architecture. The restructuring ordeal in Sri Lanka stands as a testament to the lengthy delays and potential trauma associated with such proceedings today.

Restructuring is now more difficult than in the past for several reasons. First, the ascent of China and other non–Paris Club creditors means that the official creditor base is more fragmented. Although China’s claims on high-debt MENA countries are not substantial, its emergence as a leading global creditor has rendered the restructuring process in general more political, slower, and more challenging. Second, private creditors have exhibited reluctance and tardiness in providing debt relief. Third, a significant number of MENA countries—Egypt is a prominent example—have considerable domestic debt outstanding. Creditors may in the future request an expanded restructuring perimeter to include such debt. However, most of this domestic debt is held by local banks and pensions, making its inclusion particularly problematic.

Finally, the Group of Twenty Common Framework applies only to low-income countries and therefore is not applicable to most MENA countries, which are middle-income. The exceptions are Sudan, which is finally addressing its long-standing debt issues under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative (but may have trouble proceeding because of its domestic conflict), and Yemen, a country still grappling with conflict, which will likely need time to resolve its debt problems. This new debt reality means that addressing the burgeoning MENA debt issues is a steeply uphill task.

What next?

The specter of unsustainable debt and protracted, distressing restructuring looms over high-debt MENA countries. These risks could be mitigated through a combination of growth-boosting policies, new financing, and some degree of fiscal consolidation. However, the prospects for now appear grim.

First, the world economy faces a weak forecast—growth prospects are continually being downgraded amid persistently high inflation.

Second, securing external financing will pose a significant challenge and, if procured, will carry high interest rates. The Gulf Cooperation Council’s oil-rich nations, which have traditionally provided substantial financing, have revamped their aid strategy. They now insist on the borrowers’ concrete, credible commitment to structural reforms, including those aimed at making their economies more inviting for foreign direct investment.

Third, although fiscal consolidation could be beneficial, it is not guaranteed to reduce debt, as noted in the IMF’s April 2023 World Economic Outlook. Moreover, given the tense social and political climate in high-debt MENA countries, public acceptance of expenditure cuts, especially to subsidies, will likely be difficult.

It may be tempting for these countries to continue muddling through, hoping that donors and multilateral agencies will come to the rescue. Some countries might even resort to inflation surprises to ease their domestic debt burden, as predicted in the IMF’s May 2023 Regional Economic Outlook for the Middle East and Central Asia. However, the path to genuine, lasting reform calls for more substantive measures.

Each high-debt MENA nation must take urgent steps to circumvent debt distress and potential crises. The measures will vary from country to country, but all must address key governance issues broadly (ERF-FDL 2022) and credibly commit to reform. For instance, Egypt should dismantle its overbearing regulatory system and diminish the army’s role in the economy to spur growth and should carry out solid privatization that attracts foreign investment. Jordan should implement deeper structural reforms to avert a crisis. Tunisia needs to quickly reverse the recent erosion of democracy and embark on crucial reforms. Lebanon must urgently form a government that transcends its deep-seated confessional divisions (in other words, the division of power among religious groups) and steers the country toward reform.

The chances of either the requisite reforms being implemented or the global economic climate turning favorable are slim—and both are needed. The MENA high-debt nations do have a narrow escape route from impending debt crises, but existing policies and unfavorable global developments are likely to constrict that path further. In particular, the prospects for fundamental changes in politics and economic management are dim. Consequently, some form of debt restructuring may be unavoidable. Debt restructuring, due to its inevitable economic disruption and harm, should be seen as a last resort. But if it is indeed inevitable, it is preferable to do it preemptively, as part of a broader set of corrective actions.

The highly indebted MENA nations find themselves in the path of a debt storm spawned by internal inefficiencies, poor governance, and an unforgiving global economy. Dodging this tempest will require swift, pinpointed interventions; real reform; and the readiness and ability to face up to debt restructuring. Time is of the essence; now is the moment for bold action. The question is whether these countries will undertake the needed political changes and take advantage of this critical juncture to commit to, and enact, reform—or simply continue to drift further into a sea of debt.

Further readings

Economic Research Forum (ERF) and Finance for Development Lab (FDL). 2022. “Embarking on a Path of Renewal: MENA Commission on Stabilization and Growth.” Giza, Egypt.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2023a. “Coming Down to Earth: How to Handle Soaring Public Debt.” World Economic Outlook, Chapter 3. Washington, DC, April.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2023b. Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia. Washington, DC, May.

Mazarei, Adnan, and Prakash Loungani. 2023. “The IMF’s Engagement with Middle East and Central Asian Countries during the Pandemic.” IMF Independent Evaluation Office Background Paper BP/23-01/10, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

This article was originally published by IMF Finance & Development. Read the original article.