In a nutshell

The interaction between the pandemic, school closures and the digital divide contributed to greater educational inequality in Jordan, making it harder for children in poor families to break the intergenerational transmission of inequality.

Children’s families’ socio-economic background is an important factor in their performance at school, and this was particularly evident during the pandemic.

The pandemic shed light on the importance of tackling the digital divide: government efforts should be directed to investing more in ICT infrastructure to be conducive to online teaching and learning.

From the outbreak of Covid-19 in early March 2020 up to the end of September that year, Jordan had one of the lowest national numbers for cumulative deaths per million, ranging from 0.8 to 6 (Ritchie et al, 2020). But while the country was credited with being one of the strictest about closures and restrictions on gatherings and travel, this put huge pressure on the economy (Jensehaugen, 2020; Krafft et al, 2021). GDP growth contracted to 1.6% in 2020 compared with 1.9% in 2019 (World Bank, 2021).

In response to the pandemic, Jordan’s ministry of education advised schools to cease face-to-face learning and move all their educational activities to virtual learning models. The education system responded with online learning and television as a substitute for classroom instructions (Jordan Strategy Forum, 2021).

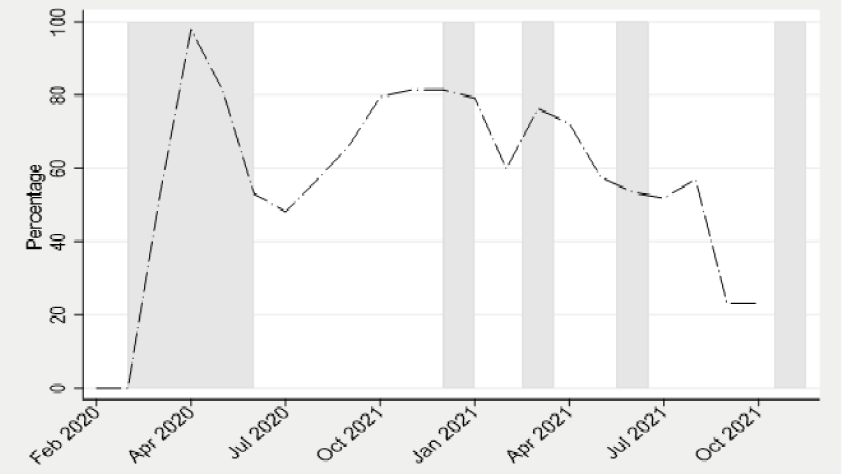

Figure 1: Stringency index and school closure in Jordan

Source: Author’s calculations; Data from Our World in Data.

Note: The shaded areas show times of school closure in Jordan. The stringency index is represented by the line. Each point on the graph represents the mean of the monthly stringency index collected daily. The stringency index is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closure, workplace closure, travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100=strictest). If policies vary at the sub-national level, the index shows the response level of the strictest sub-region.

Figure 1 shows the stringency index of responses to Covid-19 over different periods of the pandemic. In the early phase, Jordan implemented strict lockdown and curfew measures. It was among the countries adopting the most stringent full-scale lockdown measures in the Arab region:

At one point, the stringency index reached almost 100% since the government restricted people’s movement and allowed them to leave the house only in specific times to buy and fulfil their essential needs. Individuals violating these measures were penalised according to the defence law. Schools were closed until mid-June 2020.

As the first wave of the pandemic came to an end, restrictions started to be relaxed. Jordan was then among the countries that eased restrictions fast. Its stringency index fell from 100% to almost 50% by July 2020.

With the second wave in August 2020, Jordan gradually re-imposed restrictive measures. These reached the peak of their stringency by December. In 2021, the government was more responsive to the changes in the number of Covid-19 cases occurring in each period, by changing the stringency of its policy or by closing schools temporarily. Over the year as a whole, the government was loosening its stringency measures gradually.

But compared with other countries, Jordan was the country with the highest frequency of school closures in 2021, particularly because the government was able to bring schools home. The ministry of education had established an online platform named ‘Darsak’ to allow students from grade 1 to grade 12 to follow their classes virtually. The ministry also broadcast the classes on TV after school closures for 148 days (World Bank, 2021). Jordan subsidised internet costs and institutionalised the transfer of online learning through TV channels with free access (Alshoubaki and Harris, 2021).

This is alarming in the context of Jordan and other Arab countries where the outbreak of Covid-19 had a detrimental effect on school age children. Inequality in enhanced capabilities such as lack of access to internet at home deprived many children from schooling and increased out of school rates in 2020 (UNDP, 2020).

School closures and moving systems to online learning at home required more parental intervention as well as internet accessibility. The pandemic and the school disruptions contributed more to inequality of opportunities and deprivations in the means of support provided to vulnerable children and children at risk, which makes it harder for children in poor families to break the intergenerational transmission of inequality (UNDP, 2019, 2020).

Our research has explored how children’s education is influenced by school closures as a response to Covid-19 in Jordan. To estimate the drivers of children’s probability of using different learning methods during lockdown, we analyse the fourth wave of the ERF monitor survey data in Jordan, which include 2,503 respondents.

The sample restricted to 1,592 households who reported having children enrolled in school to examine the children’s educational attainment through innovative and traditional learning methods in Jordan. Out of 1,592 respondents, 49% are women, 80% are living in urban areas, 75% are Jordanians and 23% are Syrians.

In the data, we have five categories for the methods of learning: educational TV; online education; books and written materials; help from parents or any one else in the family; and in person.

It is noticeable that families play a very important role in helping their children to use online platforms and books. The usage of online education and receiving parental help contributes to unequal opportunities for kids in school. Moreover, educated parents can assist their kids in school work and measure their performance over time. The main drivers of inequality for education are families’ education and financial resources.

Government efforts should be directed to formulate programmes of literacy in information and communications technologies (ICT) so that adults can be trained to use the internet and get access to the e-learning platforms of their kids and potentially help them in their school work. Moreover, schools need to offer clear guidelines for the use of internet and online platforms for teachers and designing training programs on high-quality practices on the ICT skills.

This research project is funded by UNDP and ERF.

Further reading

Alshoubaki, Wa’ed, and Michael Harris (2021) ‘Jordan’s Public Policy Response to COVID-19 Pandemic: Insight and Policy Analysis’, Public Organization Review.

Jensehaugen, Jørgen (2020) ‘Jordan and COVID-19 Effective Response at a High Cost’, MidEast Policy Brief.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Marouani (2021) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Glimmers of Progress but Persistent Problems for Vulnerable Workers a Year into the Pandemic’, ERF Policy Brief No. 57.

Ritchie, Hannah, Edouard Mathieu, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Diana Beltekian and Max Roser (2020) ‘Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)’.

UNDP (2019) ‘Development Choices Will Define The Future’, UNDP Annual Report.

UNDP (2020) ‘COVID-19 and Human Development:Assessing the Crisis, Envisioning the Recovery’, Human Development Perspectives.

World Bank (2021) ‘Jordan’s Economic Update April 2021’.