In a nutshell

Children’s nutritional status is expected to be negatively affected by global climate change given their relative vulnerability to food insecurity shocks; developing countries in Africa are particularly vulnerable to these negative effects.

The prevalence and socio-economic determinants of stunting among children under the age of five in the Nile basin – especially in Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda – vary across space with climate change.

Social policies and public health interventions aimed at reducing the burden of childhood stunting should consider geographical heterogeneity and adaptability to climate risk factors.

Most land areas will experience more frequent hot temperature days and heatwaves by 2100, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014).

These changes in the weather have direct and indirect implications on health and wellbeing. Climate change can have a direct impact on people’s health through changing exposure to heat and cold, air pollution, emerging infections, and respiratory and water-borne diseases (Li et al, 2015; Mayrhuber et al, 2018; Greena et al, 2019).

Children are even more vulnerable than adults to these changes, as they have greater metabolic rate, lower cardiac output and greater body surface area-to-mass-ratio, which makes their bodies more sensitive to temperature changes (Bunyavanich et al, 2003; Sheffield et al, 2014; Varela et al, 2020; Elayouty et al, 2022).

The indirect impacts of high temperature on human’s health have also been identified through the effects of climate change on agriculture, water sources and general productivity levels (Hasegawa et al, 2016). Such disturbances in nutritional sources and income levels can eventually threaten food security and hence increase the risk of malnutrition in children (Mayrhuber, et al, 2018).

There is now evidence from middle- and high-income countries (Deschênes et al, 2009; Gasparrini et al, 2015; Barreca, 2018; Elayouty et al, 2022) that high temperatures are associated with increased mortality and malnutrition rates among children. Yet, little is known about the impacts of high temperatures in developing countries, although the problem is becoming more salient in these countries.

Poor populations are less capable of confronting exposure to heatwaves and its associated health effects. This is mainly attributed to their weak rates of hospitalisation and medical assistance, their weak nutritional status and their strong dependence on agriculture and natural resources, which are subject and sensitive to higher climate risks (Varela et al, 2020; Xu et al, 2017).

Quantifying the impacts of climate change on children’s health in developing countries is vital to mitigate them efficiently. But the scarcity of data in most developing countries is the main challenge limiting such studies.

Given global concerns about climate change and its impacts on health, in our research, we explore the nutrition vulnerability of children aged five and under in developing countries in Africa, and more specifically in the Nile basin countries.

Understanding how climate affects this particularly vulnerable group will contribute significantly to the decision-making process of policy-makers in Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda. This is achieved by answering key questions such as whether and how climate change affects child nutrition in the Nile riparian countries as reflected in higher stunting rates.

It is also necessary to identify which regions of the studied countries are particularly vulnerable or most affected by climate change. This is done through investigating the relationships between temperature and precipitation variability and child stunting across a diverse set of Nile basin countries taking into consideration the socio-economic factors influencing health, such as education, urban-rural discrepancies and wealth.

Globally, there are significant disparities in health and healthcare. In the context of climate change, these inequities are exacerbated in poorer countries. Most health disparities between and within countries can be avoided.

To understand the fundamental reasons of malnutrition, it is necessary to investigate the underlying socio-economic causes. The social gradients for health outcomes and the usage of health systems are revealed by disaggregating the predominant morbidity patterns for children aged under five across countries. In addition, we explore the associations between temperature and precipitation anomalies and under-five child malnutrition, and analyse the spatial variations in climate change effects and under-five stunting across different areas of the Nile basin countries.

This will help policy-makers to evaluate the impacts of changes in climate on the prevalence of poor health conditions among infants and children across the Nile basin, and identify regions that are less resilient to high temperatures. This, in turn, can be used as an early warning system to guide social policies and the public health sector on where and how to distribute its resources to save younger generations.

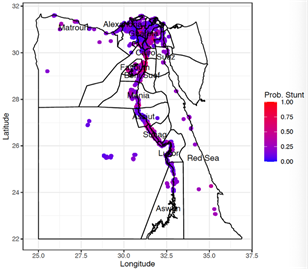

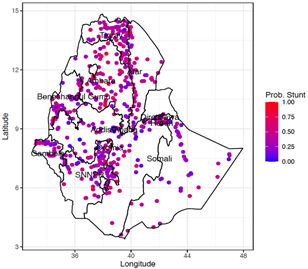

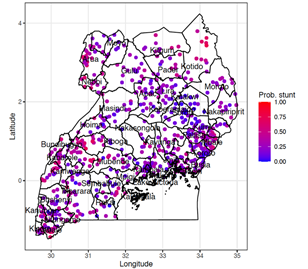

To understand the impact of climate change patterns on stunting, the probability of children aged under five being stunted is estimated across the range of temperature and precipitation anomalies. The spatial variations within each country, maps of the predicted probabilities of stunting at the observed clusters, are depicted in Figure 1.

The results highlight that the highest probabilities of stunting are clustered in Egypt, mainly in Fayoum, Sharqia and Suhag, which are densely populated governorates characterised by higher levels of poverty.

For Ethiopia, the highest probabilities of stunting are observed in Amhara, a region that experiences more than usual natural and man-made distresses, including recurring droughts and famines, civil conflicts and revolutions. These incidents seem to have significant effects on agricultural production and food insecurity, and hence child nutrition.

In Uganda, it is the southwest that suffers from higher risks of stunting relative to the rest of the country. This region has proved to have a persistently high level of child stunting due to several risk factors, mainly poor socio-economic circumstances of households, lack of good child health feeding practices, and poor hygiene practices (Bukusuba et al, 2017; and Vella et al, 1995). This further justifies more targeted interventions into poverty alleviation with a nutrition focus.

Socio-economic inequalities in health and healthcare occur everywhere. In the face of climate change, they are accentuated by poverty and underdevelopment. Most health disparities between and within countries can be mitigated through understanding the fundamental reasons of malnutrition and unhealthy behaviours.

Investigation of the underlying socio-economic causes and the impact of climate change on under-five morbidities is done by disaggregating the prevailing under-five malnutrition patterns across the Nile basin countries. Existing research mostly supports the idea that warmer and arid circumstances increase child stunting with some complexities.

Figure 1: Estimated probabilities of stunting at observed clusters in Egypt (top left), Ethiopia (top right) and Uganda (bottom).

Egypt’s warmer weather seems to increase the probability of stunting, while periods of above average precipitation are detrimental to child nutrition. This could be due to increased localised flooding, which reduces food accessibility and availability in addition to increased waterborne diseases.

The results for Ethiopia show that the relationship between precipitation and stunting follows an inverted-U-shaped pattern, which is consistent with the findings of Cooper et al (2019) and Thiede and Stube (2020). This indicates that the impacts of changes in the climate on children malnutrition vary by region.

Figure 1 highlights variations in stunting prevalence within each country and across the different countries. It is evident that efforts to reduce the burden of infants and under-five children stunting should consider geographical heterogeneity and adaptable risk factors.

The public health community’s attention has been attracted increasingly to the social determinants of health during the last two decades, which are elements other than medical care that can be affected by social policies and shape health in profound ways. Social influences at the individual, family, neighbourhood and national levels have been shown to have a significant impact on children’s health.

Mothers’ access to schooling is another important predictor of child nutrition. Improving child health in the Nile basin countries necessitates developing the social and environment conditions, mothers’ education and mothers’ access to employment. Structural adjustments to enhance access to education and work for women, as well as poverty reduction, are likely to be the most successful interventions.

The mapping of the variation in child malnutrition associated with climate change and socio-economic determinants of health can help with improving the allocation of limited resources to clusters with varying needs of healthcare and social policies.

Further reading

Barreca, A (2018) ‘From Conduction to Induction: How Temperature Affects Delivery Date and Gestational Lengths in the United States’, UCLA working paper.

Bukusuba, J, AN Kaaya and A Atukwase (2017) ‘Predictors of Stunting in Children Aged 6 to 59 Months: A Case-Control Study in Southwest Uganda’, Food and Nutrition Bulletin 38(4): 542-53.

Bunyavanich, S, CP Landrigan, AJ McMichael and PR Epstein (2003) ‘The impact of climate change on child health’, Ambulatory Pediatrics 44-52.

Cooper, MW, ME Brown et al (2019) ‘Mapping the effects of drought on child stunting’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(35): 17219-24.

Deschênes, O, G Michael and G Jonathan (2009) ‘Climate Change and Birth Weight’, American Economic Review 99(2): 211-17.

El-Ayouty A, H Abou-Ali and R Hawash (2022) ‘Does climate change affect child malnutrition in the Nile Basin?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1613.

Gasparrini, A, Y Guo et al (2015) ‘Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: A multicountry observational study’, The Lancet 386(9991): 369-75.

Greena, H, J Bailey et al (2019) ‘Impact of heat on mortality and morbidity in low- and middle -income countries: A review of the epidemiological evidence and consideration for future research’, Environmental Research 80-91.

Hasegawa, T, S Fujimori et al (2016) ‘Economic implications of climate change impacts on human health through undernourishment’, Climate change 189-202.

IPCC (2014) ‘Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’.

Li, M, S Gu et al (2015) ‘Heat Waves and Morbidity: Current Knowledge and Further Direction – A comprehensive literature review’, Public Health 5256-83.

Mayrhuber, EAS, et al (2018) ‘Vulnerability to heatwaves and implications for public health interventions – A scoping review’, Environmental Research 42-54.

Sheffield, ZX, H Su et al (2014) ‘The impact of heat waves on children’s health: a systematic review’, Int J Biometeorol.

Thiede, BC, and J Strube (2020) ‘Climate variability and child nutrition: Findings from sub-Saharan Africa’, Global Environmental Change 65: 1-10.

Varela, R, L Rodríguez-Díaz and M DeCastro (2020) ‘Persistent heat waves projected for Middle East and North Africa by the end of the 21st century’. PloS One 15(11): e0242477.

Vella, V, A Tomkins, J Nviku and T Marshall (1995) ‘Determinants of Nutritional Status in South-west Uganda’, Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 41(2): 89-98.

Xu, Z, JL Crooks et al (2017) ‘Heatwave and infants’ hospital admissions under different heatwave definitions’, Environmental Pollution 525-30.