In a nutshell

The MENA region, on average, has more inaccurate and more optimistic forecasts than the global average; inadequate data systems, growth volatility due to conflict and exposure to commodity shocks may be leading forecasts astray.

It is particularly important not to be overconfident during times of uncertainty, as overly optimistic growth forecasts can lead to economic contractions down the road.

Better forecasts would permit governments to formulate policy based on more reliable information; the private sector would also be able to plan accordingly and act based on more accurate information.

Uncertainty once again clouds global economic prospects, with the war in Ukraine upending commodity and capital markets amid worries about new Covid-19 variants. Even as the global economy re-opens – in large part, thanks to effective and safe vaccines – global inflation is at its highest level in decades and monetary policy is tightening.

The World Bank’s latest Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Economic Update (Gatti et al, 2022) forecasts that growth in the region will be 5.2% in 2022, but that growth will be uneven. Rising oil prices will benefit exporters, but the opposite is true for oil importers – and inflationary pressures from supply chain disruptions present downside risks for all economies.

In particular, increases in food prices are likely to hurt the poor the most, since they spend a higher share of their incomes on both food and energy than the better off. For example, according to the latest data available for Egypt (2017/18), households in the poorest decile of the population spend 50% of their consumption budget on food and energy while the richest decile of households spend 31%.

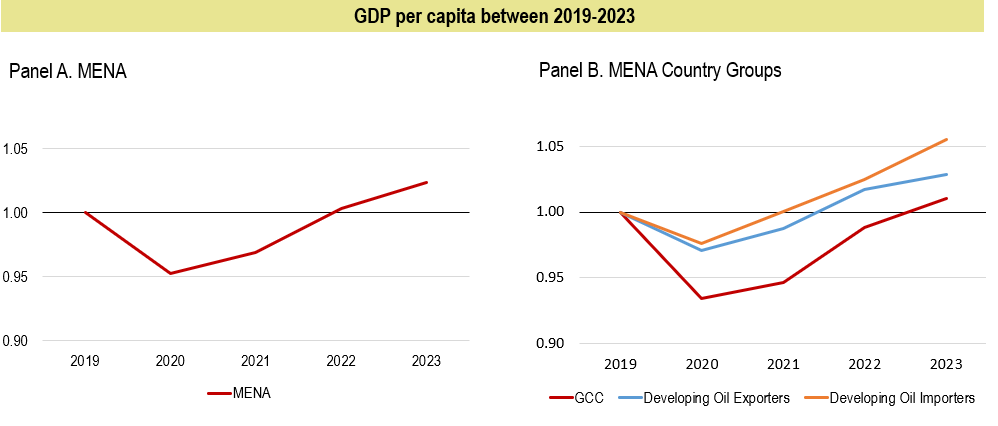

Economic growth in MENA will also be insufficient, since only 11 out of 17 countries will be likely to return to the pre-pandemic level of GDP per capita – arguably a better measure of living standards than GDP. Among the three MENA country groups, the group of GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries is the furthest away (see Figure 1). Broadly speaking, the MENA region, like the rest of the world, is not out of the woods.

Figure 1: GDP per capita between 2019 and 2023

Source: Gatti et al (2022)

During such periods of uncertainty, economic forecasts become even more important for analysts and policy-makers, who rely on them to make decisions about fiscal spending, sovereign borrowing, productive investment and social policies. It is important not to be overconfident during times of uncertainty, as overly optimistic growth forecasts can lead to economic contractions down the road.

The latest MENA Economic Update report provides an empirical assessment of the precision and biases of forecasting during the past decade and also asks whether there is scope to improve forecasts. The answer seems to be yes.

A concerted effort to enhance the availability and accessibility of good quality data in the region can improve forecasts, which would permit governments to formulate policy based on more reliable information. The private sector would also be able to plan accordingly and act based on more accurate information. Importantly, better forecasts could help plot a path through the pandemic recovery and its aftermath.

The report finds that over the past decade, growth forecasts in the MENA region have often been inaccurate and overly optimistic. A key finding is that the availability and accessibility of quality and timely information improves the accuracy of growth forecasts.

The report takes the issue of data transparency beyond internationally comparable indicators of ‘statistical capacity’ or ‘statistical performance’. It uses a ‘mystery client’ approach – where one goes to and reviews government statistics websites – to assess the availability of, and accessibility to, data on GDP, industrial production and unemployment (see Ekhator-Mobayode and Hoogeveen, 2021, for a similar approach used to evaluate microdata).

Nineteen economies in the MENA region covered by the World Bank are assessed and benchmarked against Mexico, which publishes monthly data on the three indicators of interest. Of those 19 economies, 15 report quarterly data on GDP, meeting the Mexico benchmark, although some lack information for the year 2020 entirely.

Economies in conflict such as Libya and Yemen have outdated data, from 2014 and 2017 respectively. Only 10 of the 19 MENA economies report monthly or quarterly information on industrial production. For the remaining nine, information is not readily available. Only eight economies report quarterly unemployment data, and none report data monthly.

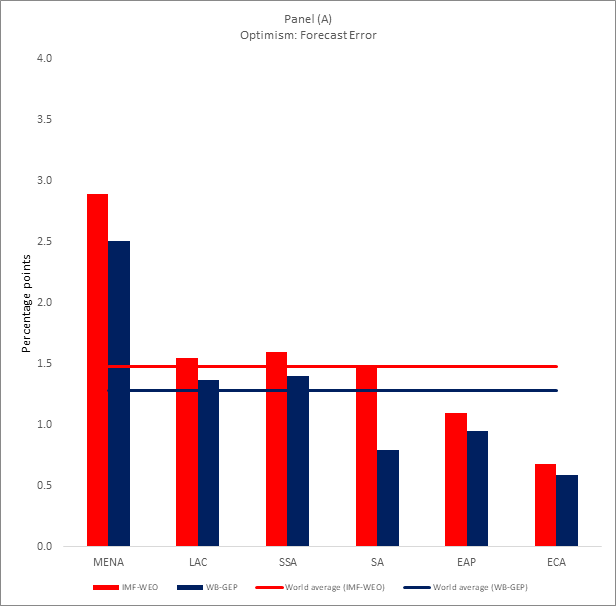

Inadequate data systems, growth volatility due to conflict and exposure to commodity shocks in the MENA region may be leading forecasts astray. The analytical findings of the report show that the MENA region on average has more inaccurate and optimistic forecasts than the global average, regardless of whether the forecast is by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or private forecasters.

The average forecast error (forecast minus realised growth) – using the World Bank’s January Global Economic Prospects (GEP) forecast over the period from 2010 to 2020 – is 2.5 percentage points for the MENA region and 1.3 percentage points globally. In other words, growth forecasts for the MENA region tended to be more optimistic than those for other regions (Figure 2).

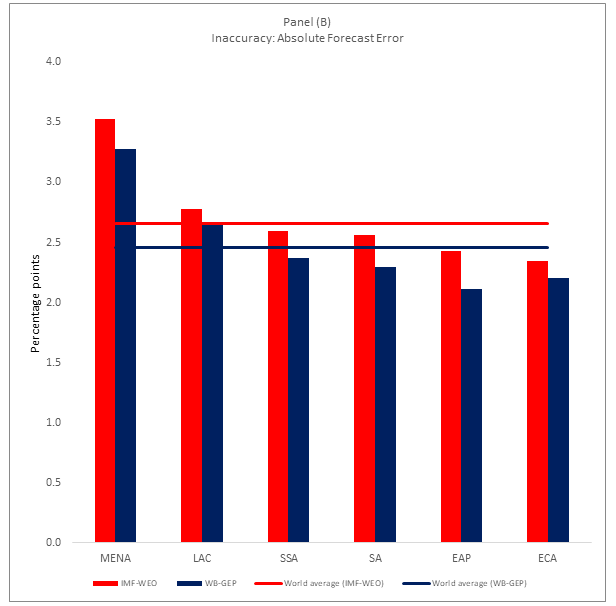

Forecasts in the MENA region also tended to be more inaccurate than those for the rest of the world. Between 2010 and 2020, again based on the World Bank January GEP forecasts, the average absolute forecast error for the MENA region is 3.3 percentage points compared with 2.5 percentage points globally.

The availability and accessibility of credible information helps forecasters to predict better. In fact, an important statistical result presented in this report suggests that poor data systems are correlated with more optimistic and inaccurate forecasts globally, particularly for the MENA region.

Figure 2: January growth forecast errors by region and institution (2010 to 2020)

Forecasts in the region can be improved in several ways. Technical assistance to governments to improve the accuracy and timeliness of national accounts could have a sizable contribution to improving the accuracy of forecasts. Finally, for countries in conflict, alternative sources of data such as satellite-based data on night-lights are crucial, and the World Bank can help to facilitate such data.

Further reading

Ekhator-Mobayode, Uche Eseosa, and Johannes Hoogeveen (2021) ‘Microdata Collection and Openness in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)’.

Gatti, Roberta, Daniel Lederman, Asif M. Islam, Christina A. Wood, Rachel Yuting Fan, Rana Lotfi, Mennatallah Emam Mousa and Ha Nguyen (2022) ‘Reality Check: Forecasting Growth in the Middle East and North Africa in Times of Uncertainty,’ MENA Economic Update April 2022.