In a nutshell

Internal migration from regions with a degrading environment to other provinces may increase the social and economic burden on the receiving regions, increasing informal settlements and marginalisation.

By contrast, source provinces may be affected by the loss of skilled labour and an insufficient working-age population for investors, who often look at the size of the market and human resources for their potential investments.

Government investments in environmental projects in the most polluted provinces may not only improve air quality, but also lead to higher levels of local economic activity, further discouraging outmigration.

Air pollution has become an important national issue in Iran in recent years. In May 2016, Reuters reported that ‘Iranian, Indian cities ranked worst for air pollution’. And according to the 2018 Environmental Performance Index (EPI, 2018), Iran was ranked 167th out of 180 countries in terms of air pollution measured by the prevalence of sulphur oxides (SOX) and nitrogen oxides (NOX).

The key sources of air pollution in Iran are transport, the extensive use of fossil fuels, outdated urban fleets of gasoline and diesel vehicles, industrial sources within and close to city boundaries, and natural dust.

Diseases associated with air pollution kill about 35,000 people every year in Iran, according to an official at the Environmental Protection Organization. In addition, several studies in Iran have shown that air pollution has negative effects on physical health (causing asthma, respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease and cancer), mental health (causing anxiety and depression), labour productivity and students’ academic performance.

One aspect of air pollution that is yet to be examined is if it explains migration behaviour across the provinces of Iran. Between 2011 and 2016, approximately 4.3 million Iranians (about 5% of the population) left their habitual residences and moved to new locations (mostly within the country’s borders). This raises the question of whether air pollution has driven residents from their habitual residences.

Several studies have tested the relationship between air pollution and actual migration (as well as the intention to migrate) in China and the United States (for example, Cebula and Vedder, 1973; Hsieh and Liu, 1983; Kahn, 2000; Chen et al, 2017; Lu et al, 2018; Qin and Zhu, 2018; Levine et al, 2019). But to the best of our knowledge, little is known about the nexus of pollution and internal migration in one of the most polluted regions of the world, the Middle East (Gholipour and Farzanegan, 2018).

In a recent study (Farzanegan et al, 2022), we examine the effect of air pollution – measured using satellite data of aerosol optical depth (AOD, an indicator of particles in the atmosphere) – on net outmigration. The dependent variable in our research is the net outmigration ratio, defined as the population leaving two major cities of a province minus new arrivals, divided by their combined total population.

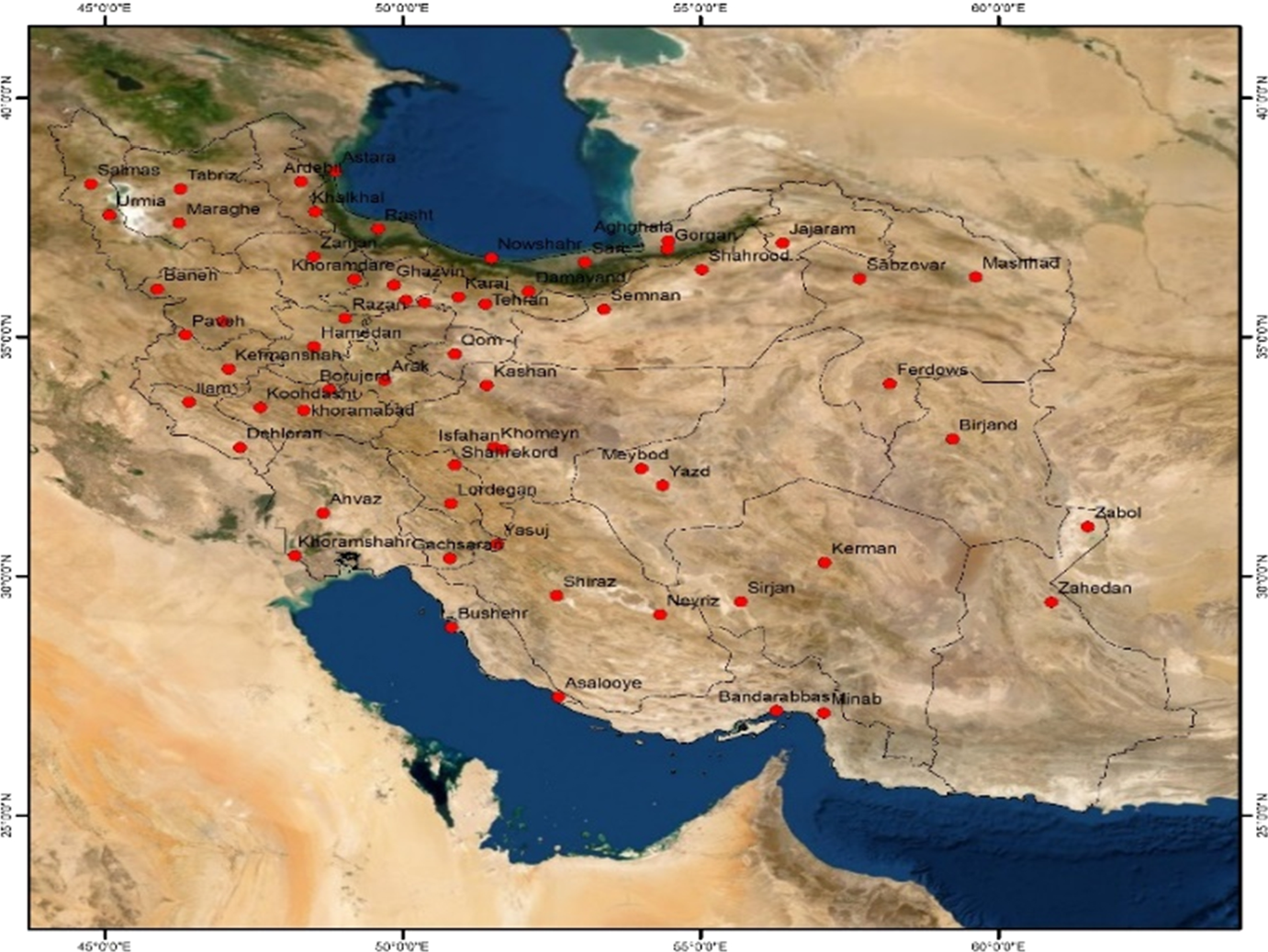

We analyse data from the 2011 and 2016 National Population and Housing Censuses for 31 provinces in Iran. Figure 1 shows the location of each sample city in Iran.

Figure 1: Location of sample cities in Iran

Source: Farzanegan et al, 2022

The net outmigration ratio varies from a minimum of -0.08 (Semnan in 2016) to a maximum of 0.06 (Lorestan in 2011 and Chaharmahal Bakhtiari in 2011), with an average of -0.003. In total, 50% of the provinces have a net outmigration ratio of less than zero, while the net outmigration ratio of others exceeds this level.

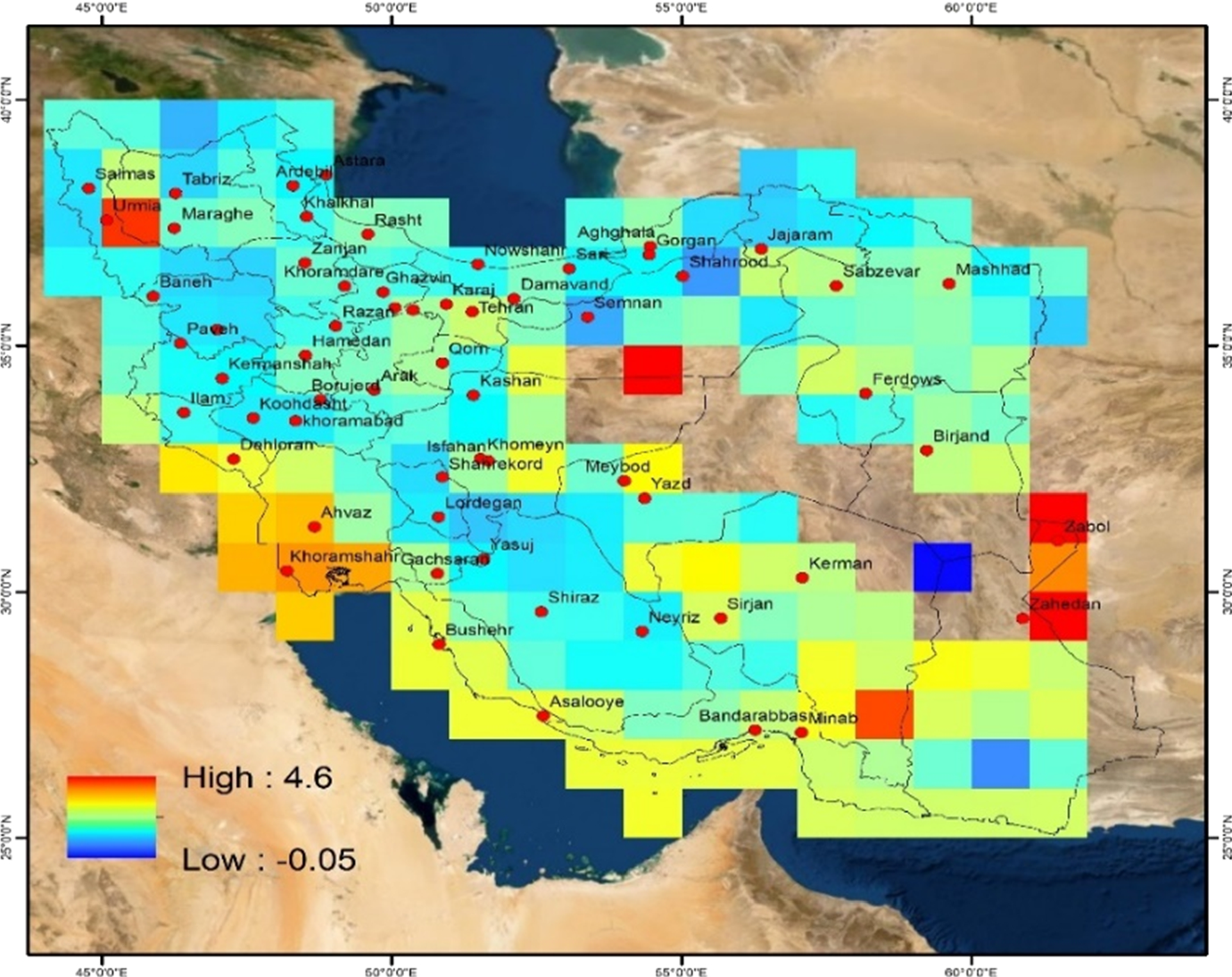

We use remote sensing data to measure AOD across the provinces of Iran. The southern part of the country has suffered more from air pollution compared with the northern part. The average AOD values in the study area are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Averaged AOD of cities included in our study over the period 2007 to 2016

Source: Farzanegan et al, 2022

Dust storms are the main source of AOD in Iran, except in metropolitan cities (such as Tehran and Isfahan), where urban pollutants typically dominate. The deserts in Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Syria, as well as local soil erosions, are the main dust sources in Iran. Therefore, the southern and western provinces of Iran have higher AOD than the northern provinces. Zahedan, Zabol, Ahvaz, Khorramshahr and Urmia were the most polluted cities in Iran during the period of our study.

Our findings suggest that higher levels of air pollution in provinces significantly increase the levels of net outmigration from the affected provinces. This increasing effect is robust while controlling for other economic and social drivers of internal migration.

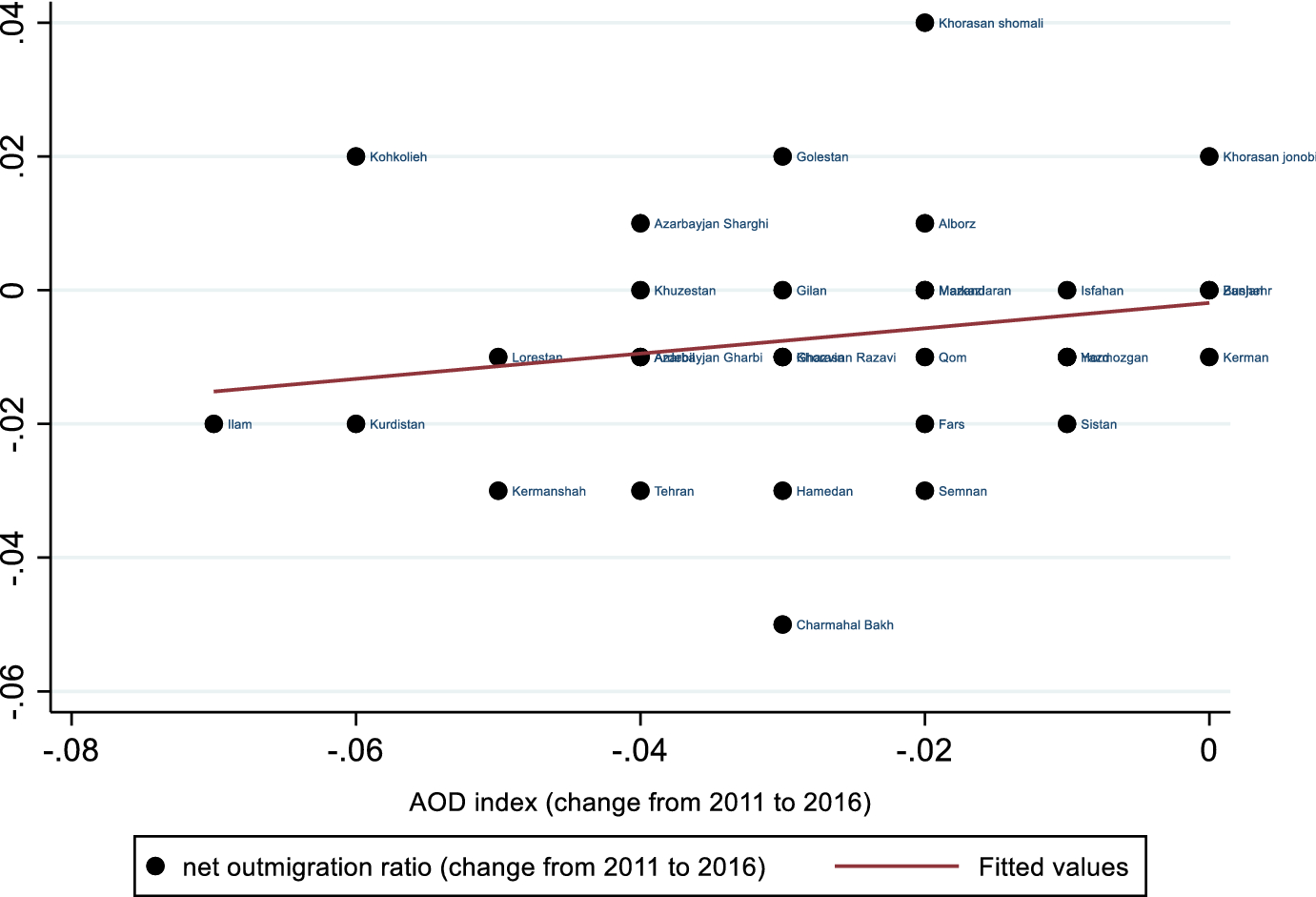

Figure 3 shows the scatter plot of the net outmigration ratio and AOD. The positive slope of the trend line illustrates our main result.

This finding is closely related to the theoretical work of Wolpert (1996), who was among the first researchers to explain the relationship between non-economic variables (environmental quality) and migration behaviour. More specifically, the 1996 study argued that migration is a response to stress experienced from the current residential location, with residential ‘stressors’ including environmental ‘disamenities’ such as pollution, congestion and crime.

Wolpert’s model suggests that these ‘stressors’ bring about ‘strain’, which may lead to consideration of residential alternatives (Hunter, 2005). In other words, a location’s environmental quality (as an important component of the quality of life) plays a role in shaping individual and household internal and international migration decisions (Kahn, 2000; Hunter, 2005).

We also find that higher levels of income per capita, as a measure of economic activities and market potential, discourage internal outmigration from the provinces of Iran.

Figure 3. The association between net outmigration and AOD

Source: Farzanegan et al, 2022

Internal migration from regions with a degrading environment to other provinces may increase the social and economic burden on the management of the receiving regions, increasing informal settlements and marginalisation. By contrast, source provinces can be affected by the loss of skilled labour and an insufficient working-age population for investors, who often look at the size of the market and human resources for their potential investments.

Our findings suggest that policy-makers could control forced internal migration by focusing more on environmental projects and addressing the factors that contribute to the degradation of air quality (particularly in two of the most polluted provinces of Iran, Khuzestan, and Sistan and Baluchestan). Such investments by the government in critical provinces may also lead to higher levels of local economic activity, which may dampen internal outmigration from the province (independent of the role of AOD).

Nevertheless, as shown by Gholipour and Farzanegan (2018), the final effect of environmental expenditures by governments on pollution depends on the quality of institutions. Therefore, institutional quality (for example, control of corruption) should be improved alongside increasing government expenditures on environmental protection.

Further reading

Cebula, RJ, and RK Vedder (1973) ‘A note on migration, economic opportunity, and the quality of life’, Journal of Regional Science 13: 205-11

Chen S, P Oliva and P Zhang (2017) ‘The effect of air pollution on migration: evidence from China’, NBER Working Paper No. 24036.

EPI (2018) Environmental Performance Index.

Farzanegan, MR, HF Gholipour and M Javadian (2022) ‘Air pollution and internal migration: evidence from an Iranian household survey’, Empirical Economics.

Gholipour, HF, and MR Farzanegan (2018) ‘Institutions and the effectiveness of expenditures on environmental protection: evidence from Middle Eastern countries’, Constitutional Political Economy 29: 20-39.

Hsieh, C, and B Liu (1983) ‘The pursuance of better quality of life: In the long run, better quality of social life is the most important factor in migration’, American Journal of Economics and Sociology 42: 431-40.

Hunter, LM (2005) ‘Migration and environmental hazards’, Population and Environment 26: 273-302.

Kahn, ME (2000) ‘Smog reduction’s impact on California County growth’, Journal of Regional Science 40: 565-82.

Levine, R, C Lin and Z Wang (2019) ‘Pollution and human capital migration: Evidence from corporate executives’, Berkeley Haas working paper.

Lu, H, A Yue, H Chen and R Long (2018) ‘Could smog pollution lead to the migration of local skilled workers? Evidence from the Jing-Jin-Ji region in China’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling 130: 177-87.

Qin, Y, and H Zhu (2018) ‘Run away? Air pollution and emigration interests in China’, Journal of Population Economics 31: 235-66.

Wolpert, J (1996) ‘Migration as an adjustment to environmental stress’, Journal of Social Issues 22: 92-102.