In a nutshell

If technological change remains on its current trajectory, which is labour-displacing and skill-intensive, workers with high school education or less, many in low-wage occupations, will be the first to feel the full brunt of technological change.

But by then, digital technologies will have advanced to a point where it will be possible to automate not just the routine activities in manufacturing and services but also many of the higher cognitive and non-cognitive functions performed by humans.

The heterogeneity of Arab countries means that in response to new technologies, governments will have to develop customised policies to bolster productivity, generate employment, contain inequality and minimise poverty.

The diffusion of digital technologies has aroused hopes that it will revive productivity, which has stagnated worldwide for more than a decade. But these hopes are matched by fears that labour will be displaced, particularly workers with few skills, and that this could result in worsening income inequality, something that is already a concern in many countries (World Inequality Lab, 2018; UNDESA, 2020).

Frey and Osborne (2017) were among the first to announce the arrival of a ‘digital revolution’. They were followed by the McKinsey Global Institute (2017), Berg et al (2018), Muro et al (2019), Susskind (2019), Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020, 2021) and the list goes on.

Although OECD countries are the focus of much of the research and forecasts, reports issued by the International Labour Organization, the World Bank (Beylis, 2021) and others note the potential benefits for developing economies, but warn that the accelerating adoption of digital technologies, especially since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, could lead to a winnowing of jobs in both manufacturing and services (Yusuf, 2021; Chernoff and Warman, 2021).

Whether the projected displacement of jobs comes to pass remains to be seen. Research has not yet uncovered a significant erosion of jobs linked to automation in either advanced or developing countries. There has been displacement, but nothing that approximates the projections. But in a few advanced economies, the combined effects of technology, globalisation, industrial concentration and other factors have increased inequality, and the share of labour in GDP has drifted downwards worldwide.

Optimists are convinced that digitisation will eventually revive productivity growth as earlier ‘general purpose technologies’ such as electricity did with a lag, and that new occupations will materialise creating a plenitude of well-paid job opportunities. But this desired outcome is not a given and countries need to harness appropriate digital technologies proactively while at the same time taking steps to ensure that they deliver on their promise.

Were productivity to continue stagnating and labour-displacing technological change lead to an increasing dispersion of incomes, many developing countries risk being caught in a low growth trap because inequality could exacerbate the growth inhibiting effects of a productivity drought (OECD, 2014; Dabla-Norris et al, 2015).

Inequality has caught the attention of politicians and researchers in several Arab countries as poverty and precarity – the size of the vulnerable population – is on the rise because of slow growth in productivity and GDP, the inadequacy of the social safety net and the poor quality of public services. Intergenerational mobility is waning and there are fewer job openings for those in lower quintiles whose numbers are increasing (Yousef et al, 2020).

By sowing uncertainty, the pandemic could depress investment in more productive industries and constrain reallocation. The hope is that the spread of digital technology could improve productivity and even narrow income differentials, although that would depend on the coordinated implementation of macroeconomic, education, and labour market policies (World Bank, 2021). A McKinsey report (2016) on the Middle East indicated that the region could add nearly 4% of GDP by fully exploiting the potential of digital technology.

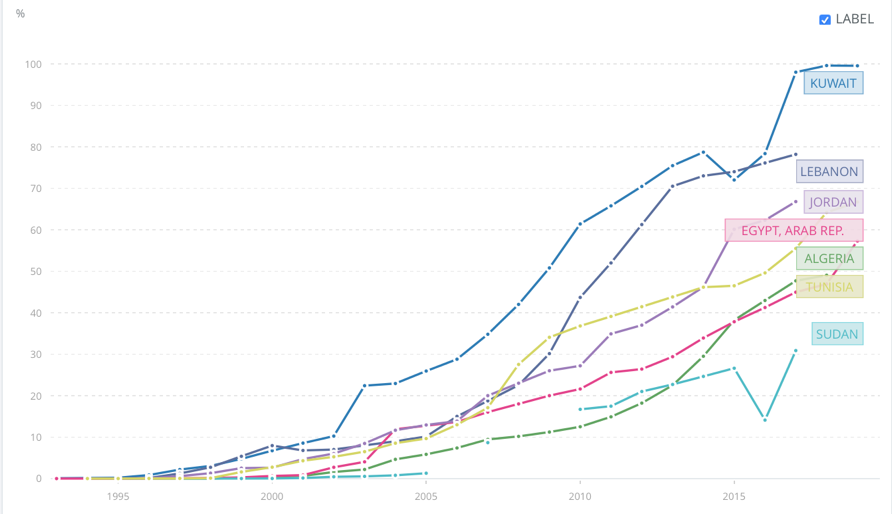

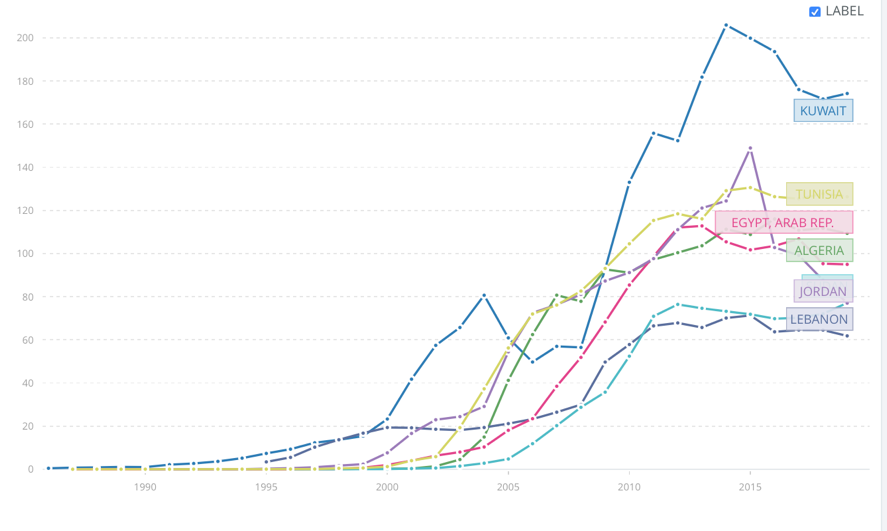

Considering the heterogeneity of the 22 Arab countries, the spread of digital technologies and its implications for inequality vary considerably. A benchmarking of these countries using two indicators of digital technology usage (the internet and mobile devices) shows that the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) clearly lead the field, followed by the middle-income industrialising ones, such as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria.

The low-income and ‘troubled’ countries, including Somalia, Sudan, Mauritania, Djibouti, and Comoros, barely make the cut and their entry into the digital economy lies far in the future (see Figures 1 and 2).

Digitisation has progressed in the GCC countries aided by technology embodied in imports of human and physical capital. Others, including Oman, still fall well short of the levels achieved by upper middle-income Southeast Asian economies such as Malaysia. And all the Arab countries are deficient in ICT supply and innovation (OECD, 2017).

Figure 1: Individuals using the internet (% of population)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators (2021)

Figure 2: Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators (2021)

Thus far, digital technology is not the major determinant of income distribution in the Arab region. Automation has not displaced workers in the labour-intensive assembly and processing activities in Arab countries, although more automated equipment is undoubtedly in use to produce items such as garments, food products and footwear. The petrochemical and metals industries were highly automated from the very outset.

The public sector is a large employer in Arab countries, absorbing between a fifth to over 90% of the national workforce in some GCC countries. Adoption of digital technology does not appear to have caused a cutback in public sector employment. In the GCC countries, there is ample evidence that the technology is in widespread use (the distribution of income as measured by the Gini coefficient has remained stable for almost two decades). But trends in labour and total factor productivity indicate that the diffusion and depth of usage are at an early stage.

Rankings of Arab countries on the Global innovation Index and the Networked Readiness Index, which declined between 2011 and 2017, also suggest that technology assimilation is making slow headway.

One study notes: ‘Only 6% of the Middle East public lives under digitised smart government… Countries in the region lag far behind in business digitisation, with low availability of venture capital funding for start-ups and low shares of the workforce employed in digital careers and industries’ (Mostafa, 2019). And Bohsali et al (2017) find that less than 2% of the GCC workforce were holding digital jobs, compared with the European Union average of 5.4 with considerable room for enlargement.

The penetration of digital technologies is bound to increase. Once more manufacturing activities and services are automated, the pressures already besetting industrialised economies – including the hollowing of the middle class – will surface. If technological change remains on its current trajectory, which is labour-displacing and skill-intensive, workers with high school education or less, many in low-wage occupations, will be the first to feel the full brunt of technological change.

But by then, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies will have advanced to a point where it will be possible to automate not just the routine activities in manufacturing and services, but also many of the higher cognitive and non-cognitive functions performed by humans.

Jobs requiring human creativity, dexterity, social skills, empathy, and decision-making capacity would remain, as would manual jobs that machines will not be equipped to perform. But how many high-end well-paid jobs there will be – whether in existing occupations or in entirely new ones – is unknown. Also unknown is the likely future profile of jobs in Arab countries in a digitising world.

If workers cannot be absorbed by the (overstaffed) state sector or into new occupations because they lack the skills, unemployment, wage compression and inequality, could increase. The heterogeneity of Arab countries means that the governments of these countries will have to customise policies based on domestic circumstances and resources.

But all will have to use a mix of the following four to bolster productivity, generate employment, contain inequality, and minimise poverty:

- First, they can redouble efforts to inculcate the skills that will be in demand using all the instruments at their disposal, complementing other actions to stimulate growth.

- Second is to promote those technologies that are less labour-displacing – by discouraging excessive automation – and steering clear of subsidies that provide incentives for capital-intensive production techniques.

- Third are policies that support start-up activity by making more risk capital available to firms with promising innovations, which complement humans while augmenting their productivity (Acemoglu, 2021).

- Fourth is to ensure that all those who risk falling below the poverty line are guaranteed a basic income by means of tax and transfer mechanisms. Universal basic income (UBI) – targeted or not – could be an option for governments with the requisite fiscal capacity and political support for redistribution.

Further reading

Acemoglu, D (2021) ‘AI’s future does not have to be dystopian’, Boston Review.

Acemoglu, A., and P Restrepo (2020) ‘Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets’. Journal of Political Economy.

Acemoglu, D, and P Restrepo (2021) ‘Tasks, automation, and the rise in US wage inequality’, NBER Working Paper.

Berg, A, EF Buffie and L-F Zana (2018) ‘Should we fear the robot revolution?’, IMF Working Papers.

Beylis, G (2021) ‘Covid-19 accelerates technology adoption and deepens inequality among workers’, World Bank.

Bohsali, S, S Papazian and M Rizk (2017) ‘Empowering the GCC workforce’. Strategy&.

Chernoff, A, and C Warman (2021) ‘Down and out: Pandemic-induced automation and labour market disparities of Covid-19’, VoxEU.

Dabla-Norris, E, et al (2015) ‘Causes and consequences of income inequality’, IMF.

Digital McKinsey (2016) ‘Digital Middle East: Transforming the region into a leading digital economy’.

Frey, CB, and MA Osborne (2017) ‘The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114.

Muro, M, R Maxin and J Whiton (2019) ‘Automation and AI’, Brookings Institution.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017) ‘Jobs lost, jobs gained: workforce transitions in a time of automation’.

Mostafa, S (2019) ‘How to measure digital transformation in Arab countries’, UNDP Arab Development Portal.

OECD (2014) ‘Focus on inequality and growth’.

OECD (2017) ‘Benchmarking digital government practices in MENA countries’.

Susskind, D (2020) World without work, Metropolitan Books.

UNDESA (2020) ‘World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a rapidly changing world’.

World Bank (2021) ‘Global Productivity: Trends, drivers, and policies’.

World Inequality Lab (2018) ‘World Inequality Report 2018’.

Yousef, TM, et al (2020) ‘The Middle East and North Africa over the next decade: Key challenges and policy options’, Brookings Institution.

Yusuf, S (2021) ‘Digital Technology and Inequality: The impact on Arab countries’, ERF Working Paper No. 1486.