In a nutshell

Economic and political proximity to the IMF’s major shareholders matter for a country’s likelihood of obtaining a non-concessional loan.

The objective of most IMF loans is to stabilise the economy in the short run; they typically do not improve long-term growth.

Compared with autocratic regimes, democratic regimes improve the effects of IMF loans on growth and other outcomes, such as the current account and inflation; structural variables, such as investment and schooling, do not seem to be significantly affected by loans.

Lending by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is supposed to be based mainly on technical economic considerations. But this does not seem to be the case: controversial anecdotal evidence along with some studies suggest that politics plays a large role in the IMF’s loan decisions.

Existing research on IMF lending is inconclusive, and there is not yet a consensus on its determinants and outcomes. In our research, we analyse both the economic and political determinants of IMF loans to low- and middle-income countries – including some in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) – and how the domestic politics of the recipient country affects the outcomes of these loans.

The MENA region provides an interesting example of the interactions between IMF lending and domestic politics (Table 1). Apart from regimes in periods of transition, it seems that those most MENA countries that resorted to the IMF over the period from 1992 to 2020 are classified as anocracies or autocracies, according to Polity Scores – a measure that ranges from -10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy).

Since autocratic regimes can be less constrained by public opinion and competitive elections, they can potentially negotiate more easily with the IMF, which would increase their likelihood of obtaining a loan (Sturm et al, 2005). Furthermore, MENA countries’ demand for IMF lending increased after the Arab Spring uprisings. So there is a strong economic justification for this increase, including the significant deterioration in these countries’ external accounts and fiscal balances.

Yet from a political perspective, an IMF agreement can also help a government to push unpopular policies that can face domestic resistance. For example, rejecting a policy suggested by the IMF can be more costly for domestic opposition since it can send negative signals to creditors and investors (Przeworski and Vreeland, 2000).

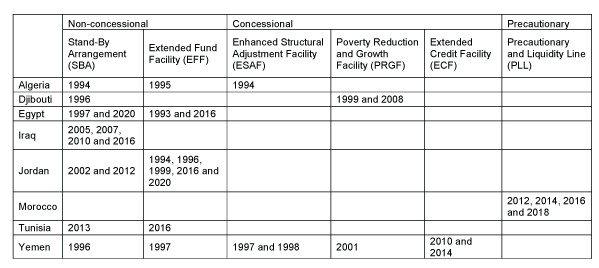

Table 1: IMF arrangements in MENA countries (start years of programmes), 1992-2020

Source: Compiled by authors based on data from the IMF Monitoring of Fund Arrangements (MONA) Database

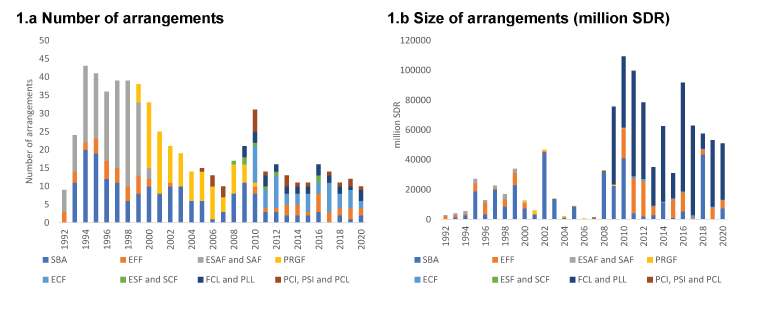

The evolution of the IMF’s lending tools also entails some political economy dynamics (see Figure 1). First, the Fund responded to critics of two of its early concessional facilities – the Structural Adjustment Facility (SAF) and the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) – and replaced them with the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) in 1999.

The SAF and ESAF were criticised for several reasons, mainly related to the absence of social considerations. Critics perceived these programmes as promoting short-term stabilisation objectives ahead of other important social objectives, and it was claimed that poverty worsens under these programmes.

Second, the global financial crisis of 2007-09 reignited debates on the role and legitimacy of the IMF. The IMF’s response included introducing new facilities for concessional lending, namely the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), the equivalent of the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for low-income countries, the Standby Credit Facility (SCF) and the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF).

Our econometric analysis of the determinants of IMF loans shows that economic and political proximity to the IMF’s major shareholders (the permanent members of the UN Security Council: the United States, France, China and the UK) matter for the likelihood of obtaining a non-concessional IMF loan (SBA and EFF).

The proxies we use for economic and political proximity are based on bilateral trade and vote similarity in the UN General Assembly, respectively. The weighted voting and lending procedures at the Fund can give a room for political dynamics (Thacker, 1999). Hence, major shareholders can have strong influence on IMF decisions, and they can be inclined to provide lending to some countries over others.

As per the outcomes of IMF lending, we find that most of the loans exert either an insignificant or negative effect on the trend component of GDP growth. This confirms that in some cases, most of the loans target stabilising the economy in the short run without changing its structure or improving its long-term steady growth.

Figure 1: IMF lending by type of arrangements, 1992-2020

Source: Compiled by authors based on data from the IMF Monitoring of Fund Arrangements (MONA) Database

We also examine how IMF loans can exert a differential impact on economic growth and other macroeconomic outcomes (stabilisation variables and structural variables) depending on the regime type (autocratic, anocratic or democratic).

Our results suggest that compared with autocratic regimes, democratic regimes improve the effects of IMF loans on economic growth and other outcomes (such as the current account and inflation).

The channels through which a democratic regime affects the implementation of an IMF programme are as follows. In democratic regimes, negotiations of an agreement are generally complicated due to the inclusion of different stakeholders (including lobbies, trade unions and various chambers).

In addition, the more complicated the negotiations, the more accountable the executive power will be once the loan is obtained. Clearly, governments that are more accountable will be obliged to improve macroeconomic outcomes to be re-elected.

Finally, our findings show that structural variables (such as investment and schooling) do not seem to be significantly affected by IMF loans.

Policy implications

We believe that discussion of IMF loan determinants and outcomes is timely and important. The current context of the Covid-19 crisis reinitiates debate on the role of the IMF given that developing countries, including MENA countries, are more vulnerable to the crisis. As such, this latest global crisis requires pragmatic solutions with international coordination in which the IMF is supposed to play a pivotal role along with domestic stakeholders.

Our results highlight the importance of democratic accountability. Indeed, the latter is perceived as a justification for the uses of power (or the use of loans), which leads to good governance of the loans, enables the implementation of checks and balance, and allows the public greater control over the use of public resources (which is what the loan represents). This improves the effect of the loans on macroeconomic outcomes.

Further reading

Barro, RJ, and J-W Lee (2005) ‘IMF Programs: Who is Chosen and What Are the Effects?’, Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 1245-69.

Bird, G, and D Rowlands (2017) ‘The Effect of IMF Programmes on Economic Growth in Low Income Countries: An Empirical Analysis’, Journal of Development Studies 53(12): 2179-96.

Bird, G, and D Rowlands (2001) ‘IMF lending: how is it affected by economic, political and institutional factors?’, Journal of Policy Reform 4(3): 243-70.

Przeworski, A, and JR Vreeland (2000) ‘The effect of IMF programs on economic growth’, Journal of Development Economics 62: 385-421.

Sturm, JE, H Berger and J De Haan (2005) ‘Which Variables Explain Decisions on IMF Credit? An Extreme Bounds Analysis’, Economics and Politics 17(2).

Thacker, SC (1999) ‘The High Politics of IMF Lending’, World Politics 51(1): 38-75.

Youssef, J, and C Zaki (2021, forthcoming) ‘On the Determinants and Outcomes of IMF Loans: A Political Economy Approach’, ERF Working Paper Series.