In a nutshell

The average Iranian lost an accumulated sum of approximately US$34,660 over the period 1978-88, an average annual real per capita income loss of US$3,150. But the long-term effects of experiencing war conditions on Iranians’ socio-economic or political preferences have been neglected.

Data from the World Value Survey provide evidence that Iranians who experienced the Iran-Iraq war during the critical years of early adulthood place a high priority on their country having strong defence forces.

The probability of supporting strong defence if an individual was in early adulthood – ‘the impressionable years’ – during the war increases if they have higher levels of confidence in government.

The Iran-Iraq war, which lasted from 1980 to 1988, was associated with a significant economic and human costs, some of which are estimated in studies by Farzanegan (2020 and 2021). What have not previously been empirically tested are the long-term consequences of experiencing war conditions by Iranians on specific socio-economic or political issues. In new research, we examine the impressionable years hypothesis in the context of Iran-Iraq war and its long-term consequences.

As noted by Giuliano and Spilimbergo (2014), the impressionable years are those years that shape individuals’ basic values, attitudes and world views. Krosnick and Alwin (1989) and Newcomb et al (1967) present evidence on significant (political) socialisation between the ages of 18 and 25. Other studies also find evidence of the important role of historical environment during the impressionable years on basic attitudes and world views (see Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2021 for a list of these studies).

The impressionable years hypothesis has been tested in economic research. For example, Giuliano and Spilimbergo (2014) find that ‘individuals who grew up during a recession tend to support more government redistribution and believe that luck is more relevant than effort in determining economic success in life’. They also argue that large macroeconomic shocks experienced during early adulthood shape preferences for redistribution.

Similarly, Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln (2007) show that after German reunification, East Germans (who lived under a communist regime) are more in favour of redistribution and state intervention than West Germans. Ehrmann and Tzamourani (2012) find that inflation memories play an important role in shaping preferences for price stability. In addition, there is a large number of studies that have examined the long-term consequences of conflicts on political attitudes and actions (see Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2021 for a review of these studies).

The role of memories of the war is also mentioned by Iranian politicians as justification for defence programmes. For example, the Iranian foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, defended Iran’s ballistic missile programme in defiance of Western and Israeli criticism in an interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, referring to the memories of the Iran-Iraq war:

[Y]ou know, we go back to a history where our cities were being showered with missiles from Saddam Hussein… and Iran did not have a single missile to work as a deterrence against its citizens.

The impact of war on young people in the impressionable years

One of the main hypotheses examined in our study is as follows:

Individuals who have experienced (directly or indirectly) the Iran-Iraq war (in full or in part) in their early adulthood have a higher preference for stronger national defence forces.

We use data from the World Value Surveys Wave 5 (2005-09). The data were collected from the national population, both sexes, 16 years and over for the period June to August 2005. The survey procedure was based on personal face-to-face interview.

We find a positive association between those in the 18-25 age group in any year of the war and choice of strong defence as the first priority of the country. We also examine whether this is related to their experience and memory of war or is simply an age cohort effect regardless of socio-economic or war and peace conditions – that is, the possibility that those who are in their early adulthood years have specific attitudes toward strong defence.

To address this possibility, we examine our question for two other countries that did not experience conflict or war; namely Sweden and Thailand. If we find a similar positive link between being in early adulthood (18-25 years) and support for strong defence, then this might be related to specific characteristics of this age cohort, regardless of war experience. We show that this is not the case and indeed experience of war conditions during early adulthood matters.

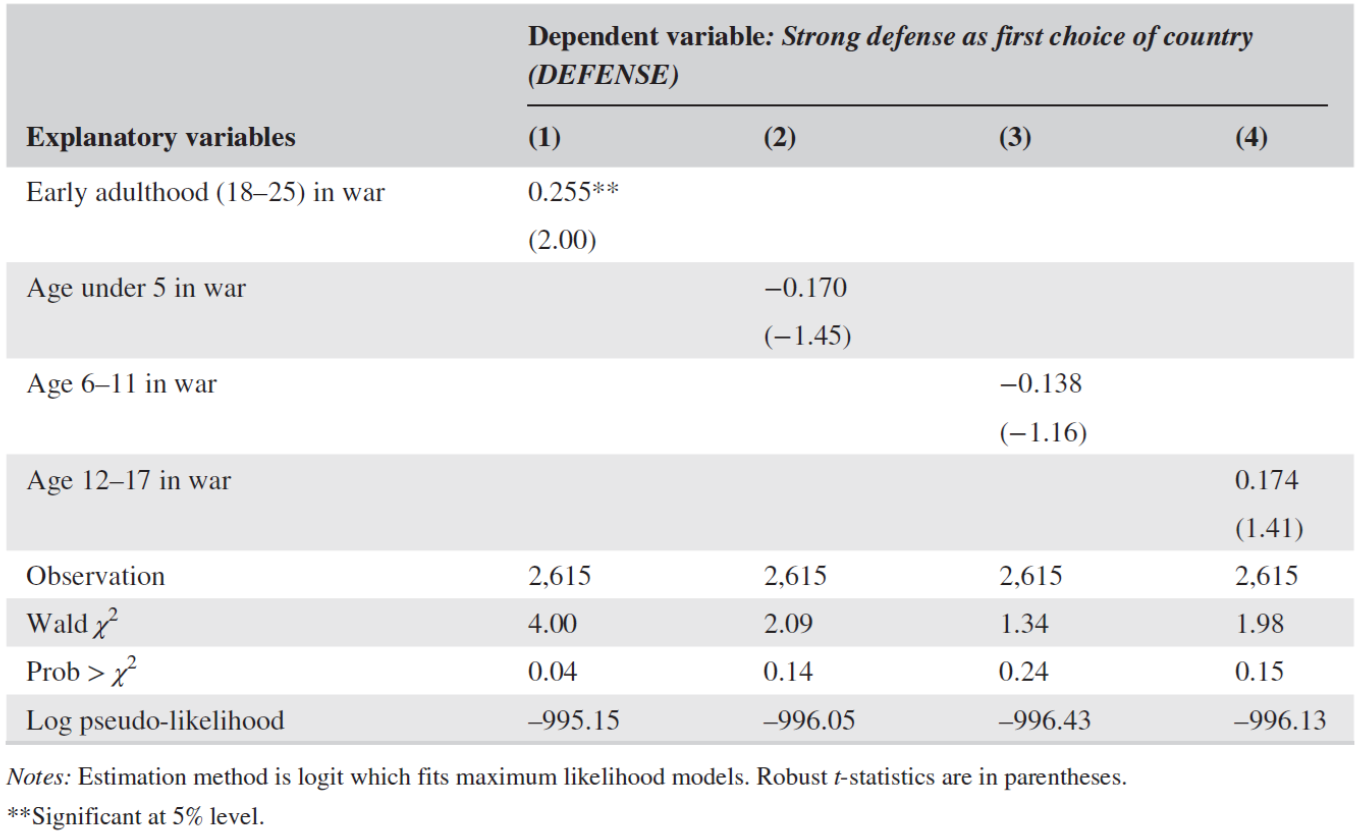

An additional check is to examine the effect of other cohorts (0-5, 6-11, 12-17) who were in these age ranges in any year of the war with Iraq. Can we also see a similar relationship with support of strong defence as in the case of impressionable years for other age cohorts?

This analysis is motivated by findings of Bellucci et al (2020) who argue that exposure to warfare in early life shapes human capital outcomes in later life and has a long-term impact on social preferences. Again, we find that the effect is only significant for impressionable years (18-25 years). Previous research mostly focuses on the negative and long-run impact of wars on child and teenage memories.

Our main results show that experiencing an asymmetric war during early adulthood is related to the formation of attitudes about the importance of strong defence for Iran’s future. The coefficient for ‘early adulthood (18-25 years)’ in Model 1 of Table 1 is positive and statistically significant. Such a positive association is not observed for other age ranges that experienced any year of the war.

To make it clearer, we calculate the marginal coefficient of our explanatory variables on the predicted probability of an individual opting for strong defence in the future. The average marginal coefficients show that being in early adulthood (18-25 years) in any year of the Iran-Iraq war period increases the probability of supporting strong defence (instead of economic growth, democracy or environmental issues) by 3 percentage points.

Table 1. Strong defence, ‘impressionable years’ versus other age cohorts

Source: Farzanegan and Gholipour (2021)

To what extent are our results robust to controlling for other drivers of individuals’ preferences for strong defence as the first choice of the state? We observe that our initial finding of a positive association between experience of the war during the impressionable years and the probability of supporting strong defence as the top priority for the country’s future is robust to the inclusion of other individual socioeconomic and political characteristics of individuals.

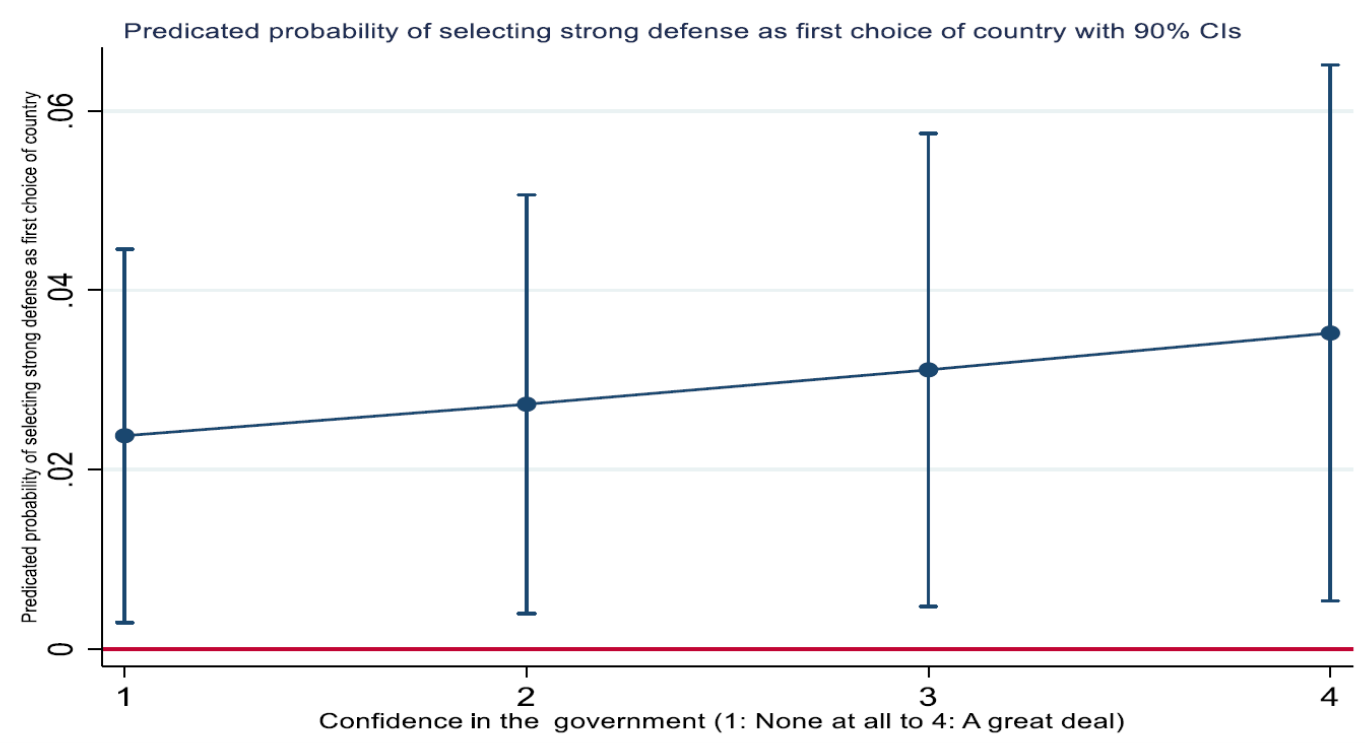

We also find that the probability of supporting strong defence if an individual was in early adulthood during the war increases at higher levels of confidence in government (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Marginal effect of experience of the war with Iraq during the impressionable years at different levels of confidence in government.

Source: Farzanegan and Gholipour (2021).

Conclusion

Our study shows that the Iran-Iraq war shocks experienced during the critical years of early adulthood are related to individuals’ preferences for strong defence as the first choice of the Iranian government.

Our findings are supported using evidence from the Wave 5 (2005-2009) of the World Value Survey, and are robust to the inclusion of a diverse set of control variables and various specifications. This support for strong defence gets stronger at higher levels of confidence in government.

Our study helps to understand the individuals’ socio-economic factors that may shape their support for stronger defence at the country level. It also helps international authorities to have a better understanding of the social drivers of Iranian military programmes.

Further reading

Alesina, A, and N Fuchs-Schündeln (2007) ‘Good-Bye Lenin (or not?): The effect of communism on people’s preferences’, American Economic Review 97: 1507-28.

Bellucci, D, G Fuochi and P Conzo (2020) ‘Childhood exposure to the Second World War and financial risk taking in adult life’, Journal of Economic Psychology 79: 102196.

Ehrmann, M, and P Tzamourani (2012) ‘Memories of high inflation’, European Journal of Political Economy 28: 174-91.

Farzanegan, MR (2020) ‘The economic cost of the Islamic revolution and war for Iran: synthetic counterfactual evidence’, Defence and Peace Economics.

Farzanegan, MR (2021) ‘Years of life lost to revolution and war in Iran’, CESifo Working Paper No. 9063.

Farzanegan, MR, and HF Gholipour (2021) ‘Growing up in the Iran-Iraq War and Preferences for Strong Defense’, Review of Development Economics 1-24.

Giuliano, P, and A Spilimbergo (2014) ‘Growing up in a recession’, Review of Economic Studies 81: 787-817.

Krosnick, JA, and DF Alwin (1989) ‘Aging and susceptibility to attitude change’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 416-25.

Newcomb, TM, KE Koenig, R Flack, and D Warwick (1967) Persistence and change: Bennington College and its students after 25 years, Wiley.