In a nutshell

Negotiators of the African continental free trade area have reached agreement on regime-wide rules of origin that will be simpler overall than those currently in place in the regional economic communities of Africa.

Hurdles remain on 18% of the 5,387 tariff lines with product-specific rules, which are in the foodstuffs, textiles and apparel, and automobile sectors.

On average, those sectors have more restrictive product-specific rules and their preferential margins are, on average twice the average in sectors where product-specific rules have been agreed.

To become fully operational in terms of reducing tariff barriers, AfCFTA signatories must submit their tariff concessions to the African Union. As of early 2021, 41 out of 54 signatory countries had submitted their offers. Signatories must also harmonise rules of origin (ROOs) across Africa’s preferential trade agreements (PTAs) to arrive at a common set of continental ROOs.

ROOs can be understood as ‘Made in Africa’ criteria that are tailored to the specifics of each product. They are necessary to ensure that only bona fide African products benefit from tariff concessions under AfCFTA.

While a ‘Made in Africa’ label may seem trivial for raw products, such as cocoa beans, tea or green coffee, which are grown locally in one country, they become increasingly complex for multi-stage products such as machinery, electronics, apparel and autos, which rely on multinational supply chains. The exact product-specific rules (PSRs) such as value-added percentage criteria, are subject to intense negotiations between the 54 signatories of the AfCFTA.

The benefits accruing from harmonisation of pan-continental ROOs can be illustrated in the following example. Under the AfCFTA, an exporter of men’s shirts (HS 6205) from Kenya to Nigeria (a member of ECOWAS, the Economic Community of West African States) will be subject to the same origin requirement as if it exports that same shirt to South Africa (a member of SADC, the South Africa Development Cooperation). In other words, countries in ECOWAS and SADC will have to apply the same origin requirement for Kenyan shirts.

In a recent study, we review progress and remaining hurdles, as the deadline to reach an agreement on tariffs and ROOs is currently set at 30 June 2021. ROOs come in two categories: regime-wide rules (RWRs), of which there are approximately 30 different ones for each PTA; and PSRs.

Across nearly all 500 PTAs globally, ROOs are often complex and filled with minutiae. They are a headache for negotiators, customs officials and exporters alike. For the AfCFTA, agreement was reached on RWRs in early 2018, but for different PSRs only for about 82%. PSRs are defined at the most detailed common product level defined by customs (around 5,300 HS6-level products) at the level of each regional economic community (REC).

We report on progress at harmonisation for the following multiple-membership PTAs engaged in negotiations: Agadir, the Arab League, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), ECOWAS and SADC. Negotiators have to compare over 850 different PSRs across the continent.

Importantly, negotiations will be complete only once 100% of the HS6 tariff codes are covered. Complications arise if a PSR is not defined for a specific HS6 code. Then a tariff reduction under the AfCFTA cannot apply because it is not clear whether the product is ‘originating’ or not, and thus whether it is eligible or not for preferential treatment.

In the absence of completely agreed PSRs, the full ambition of the ‘non-sensitive’ product list (90%) might not be realised. A temporary (interim) solution could be to rely on Article 5 in Annex 2 of the Agreement laying out the ‘wholly obtained’ criterion. However, this would be unrealistically stringent for many products on the current outstanding list (see Table 3 in the paper), such as autos and motorcycles.

Harmonisation has resulted in simpler RWRs

To evaluate if harmonisation has resulted in simpler (that is, more transparent and more flexible) RWRs, we classify each of the 16 requirements on process and the 14 requirements on certification into two categories (here): provisions providing transparency (rules on packaging, and on non-qualifying operations provide transparency on process) and provisions providing flexibility (see below provisions on certification).

All negotiating PTAs share the same set of provisions on process, but not on certification. Differences over flexibility are greater than over transparency, probably a reflection of the greater difficulty in reaching agreement on flexibility than on transparency.

Harmonisation has resulted in simpler RWRs. But further simplification would have been achieved if provisions, present in some PTAs, such as those listed below would have been adopted:

- Provision for duty-drawback.

- Provision for self-certification.

- Third-party invoicing, arguably an important missed opportunity.

- Allow for non-direct transport without burdensome documentation.

- Allowing some outward processing as a relaxation of the principle of territoriality.

Remaining hurdles

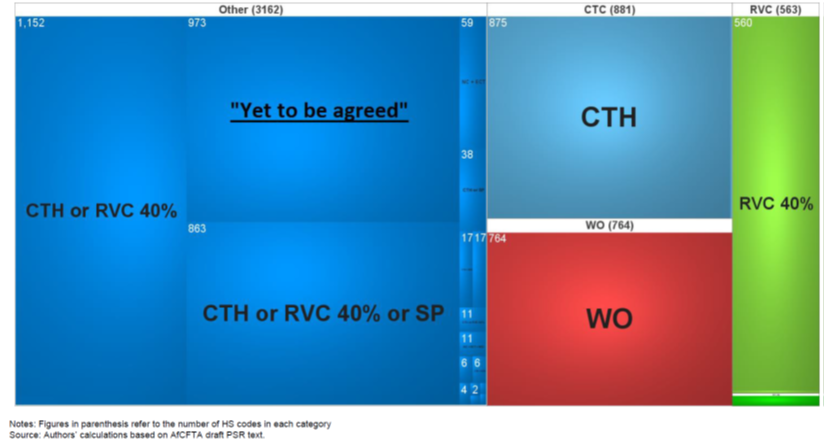

As of early 2021, negotiators have apparently reached agreement on PSRs for 82% of tariff lines: all sectors except foodstuffs, textiles and apparel, and automobiles. The figure classifies the 5,387 HS6 products under negotiation into PSR categories where agreement has been reached and those still under negotiation.

Figure 1 shows that agreement has been reached with single criteria PSR for 41% of HS6 codes (WO, RVC 40%, CTH). Agreement on another 37% has been reached for a mixed (alternative) criterion (CTH or RVC 40%, and CTH or RVC 40% or SP). (Definition of acronyms in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of PSR in AfCFTA across HS6 codes: agreed and to be agreed

Notes: WO (wholly obtained); CTH (Change of tariff heading); RVC (regional value content); SP (specific processing)

Presumably, sectors where negotiations are stuck correspond to those where interests diverge most across RECs, that is, where preferential margins (approximated by the most favoured nation tariff) are high, at least in some RECs. Comparisons between the two groups of PSRs gives the following patterns:

- Agreement has not been reached for 973 out of 5,387 HS6 products.

- Average preferential margin for PSRs under negotiation, stand at 21%, about twice the average for products where agreement has been reached.

- Regulatory distance (in the sense of different PSRs by REC at the HS6 level) is less among PSRs where agreement has been reached.

- R-index values, an indicator of the complexity and restrictiveness of PSRs (an ordinal observation-based in which a higher value indicates a more restrictive PSR – for example an RVC of 60% is more restrictive than an RVC of 40%) are higher among PSRs where agreement has not been reached.

Towards simpler business-friendly ROOs for AfCFTA

Africa is a still a region with high tariffs across-the-board, so tariff liberalisation among African countries can have substantial effects in promoting intra-regional trade, among others, through expansion of regional value chains.

Firms’ access to zero AfCFTA tariff rates in practice will hinge on agreed ROOs. ITC surveys of firms’ experiences with rules of origin consistently highlight this type of non-tariff measure as among the most burdensome and annoying, especially for manufacturing sector. Therefore, the design of ROOs matters.

The success of the AfCFTA will depend on widespread acceptance and application by businesses of the agreed ROOs, accompanied by correct enforcement and encouragement by government authorities. Design will continue to matter even if certificates of origin (COOs) are delivered electronically since preparation and validation will still be needed, one way or another.

Our detailed forensic inspection of these rules and preliminary analysis of the restrictiveness of the agreed PSRs point in the direction of rules close to those prevailing in SADC and an overall high PSR restrictiveness.

But PSRs are heterogeneous across products. Some sectors such as agrifood, rubber and wood products are quite restrictive, with ‘wholly obtained’ (WO) criteria dominating. Other sectors, such as chemicals, machinery and vehicles, give flexibility through the choice of alternative rules between a change of tariff classification (CTC) and a regional value content (RVC) criterion.

These criteria are applied extensively across the board in ECOWAS and COMESA, which are relatively liberal free trade agreements. These choices represent an ‘improvement’ in terms of simplicity and transparency over those prevailing in SADC.

But the high overall PSR restrictiveness of the AfCFTA is partially mitigated by a high trade-facilitating score for RWRs. For example, by virtue of diagonal cumulation, companies are allowed to source originating intermediate inputs from all across Africa. This should help achieve the required PSR threshold.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study that assesses systematically the landscape of PSRs for 82% of products where tentative agreement has been reached across the AfCFTA membership. While negotiations on the remaining PSRs and tariffs are still in progress, we have used three novel metrics (wording similarity, regulatory proximity and an index of restrictiveness for PSRs) to monitor progress at harmonisation.

As with all trade reforms that involve a transfer of rents (and associated costs), the AfCFTA negotiations show that agreement is difficult to reach when high rent transfers are at stake. From an economic perspective, the challenge is to agree on ROOs that are business-friendly rather than business-owned in the sense of penalising small firms by their complexity. Other suggestions include a waiver of proof of origin on MFN tariffs below 2%, and on shipments (both personal and commercial, for example, e-commerce) below a threshold, say $500.

Significantly, the two indices used to describe heterogeneity across PSRs also display expected differences. Regulatory similarity is higher among those PSRs where an agreement has been reached.

In addition, R-index values, indicators of the complexity of PSRs, are higher among PSRs where agreement has eluded negotiators. These average values between the two groups are also indirect evidence of the usefulness of these two indicators to summarise the complexity of ROOs across PTAs. If PSRs negotiated for those sectors turn out to be too restrictive, it will be a barrier, rather than a boon, for the development of regional value chains across Africa.