In a nutshell

In recent years, an unconditional cash programme for Syrian refugees in Lebanon has reached around 60,000 households annually, while a food value voucher programme has reached around 120,000 households.

The humanitarian aid programmes achieve their objectives of providing temporary relief to the extreme poor: expenditures increase substantially, children go back to school, food security increases and families engage less in livelihood coping strategies.

Despite the large transfer sizes, programme effects do not last beyond the assistance cycle – a finding suggesting that sizeable cash transfers alone might not lead to sustained poverty alleviation.

Cash-based targeted programmes are a common way to assist refugees and internally displaced persons – notably in the Middle East and North African region in conflict-affected areas in or around Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Syria. But despite the scale of international humanitarian aid effort, little is known about the effect of these assistance programmes on the wellbeing of recipients – often due to a lack of data and credible research designs, in addition to the nature of these rapidly changing environments.

In partnership with the UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, and the World Food Programme in Lebanon, we evaluated the household-level welfare effects of two of the largest humanitarian assistance programmes currently in operation.

The multipurpose cash assistance programme provides households with $175/month on an unrestricted debit card, while the food e-card programme provides $27/person/month as a food value voucher for a wide variety of foods at contracted shops around the country. In recent years, the unconditional cash programme has reached around 60,000 households annually, while the food value voucher programme has reached around 120,000 households.

Eligibility for both programmes is assigned based on a proxy means test (PMT) that uniquely ranks households in terms of a predicted level of socio-economic vulnerability – generating a sharp discontinuity in the probability of eligibility where caseloads (that is, budgets) are exhausted. This feature of the allocation system allows us to recover effects of these programmes without confounding programme receipt with household poverty or vulnerability through a comparison of recipients near the eligibility thresholds.

To this end, we use the existing UNHCR administrative database and survey data collected to evaluate the vulnerability of the refugee population in Lebanon. The UNHCR database provides the PMT scores that determine eligibility, as well as data on assistance receipt across programmes.

We use these data in an initial step to detect algorithmically the implicit thresholds in the PMT score, which can change across years due to fluctuations in budget and the potentially eligible population. We then use these thresholds to set the ‘cut-off’ point for a regression discontinuity analysis, and ensure that this recovers a valid discontinuity in assignment probability.

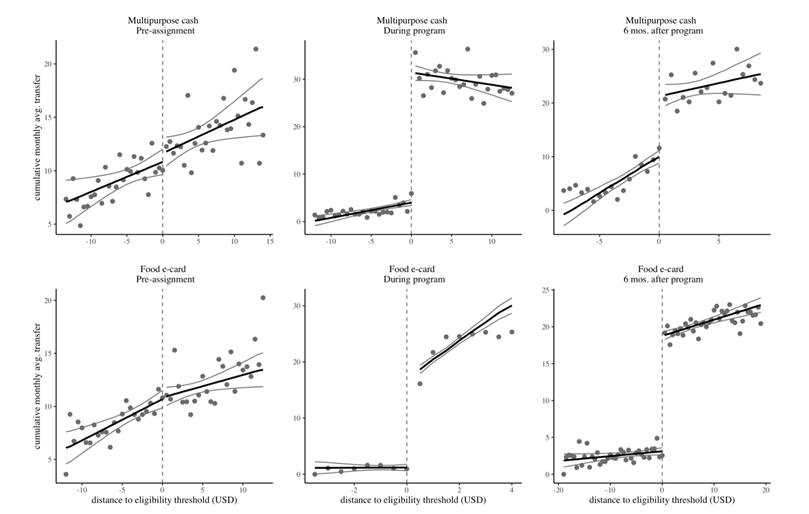

Figure 1: Assistance receipt around threshold

We then use the Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees (VASyR) survey to measure effects on dimensions of wellbeing. The VASyR data provide nationally representative repeat cross-sectional data on the refugee population, and has historically been collected annually in April to May.

We use data from three assistance cycles between 2016 and 2019, which allows us to assess the wellbeing effects both while households are receiving assistance, as well as six months after the programme cycle ends. The unique feature allows us to test an important question as to whether unconditional cash-based assistance programmes to the refugee population can have lasting effects beyond the assistance cycle.

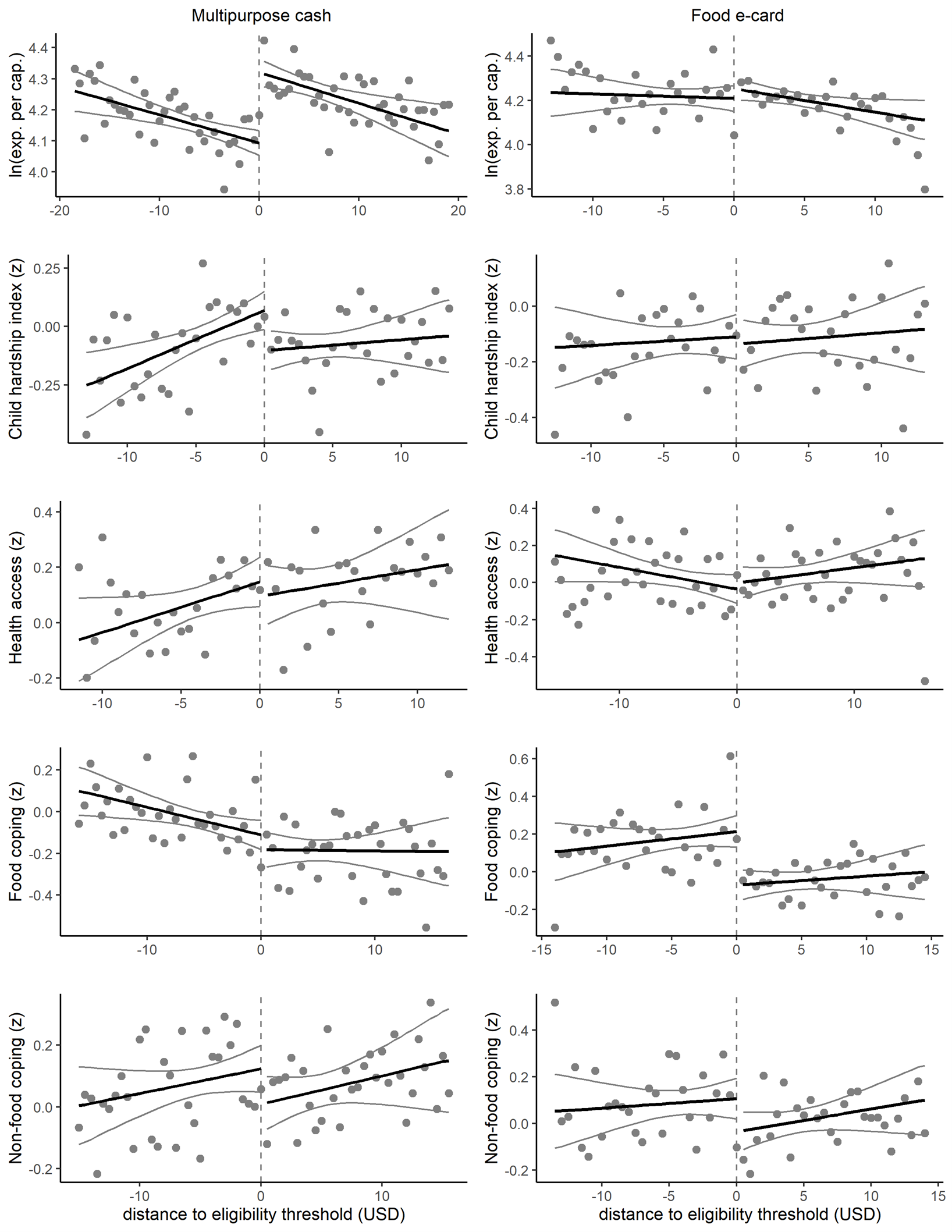

During the assistance period, as shown in Figure 2, expenditures increase substantially, children (notably boys) stop working and go back to school, food security increases and families engage less in livelihood coping strategies. Beneficiaries allocate additional income to essential consumption goods, most notably rent, food and energy. The documented effects are temporary, however, and do not persist even for six months after the programme ends despite the size of the transfers received.

Figure 2: During program effects of assistance receipt

When we further investigate why there is this non-persistence, we find evidence contrary to myopic behaviour: rather than allocating income to temptation goods, households invest in durable goods and human capital. Moreover, both programmes increase savings in cash and durable goods. But these savings appear short-lived, and are spent to buffer consumption in response to liquidity shocks.

We also show that programme benefits for continuing recipients are identical to those who are newly included – providing evidence that effects on expenditure and other outcomes do not compound or accumulate across subsequent assistance cycles. The volatility of income and expenses faced by poor households make sustained savings improbable to begin with, and costly and short-lived when possible.

Our results are consistent with an environment in which sizeable cash transfers alone might not lead to sustained poverty alleviation. The humanitarian aid programmes that we investigate achieve their objectives – to provide temporary relief to the extreme poor, helping to cope with day-to-day vulnerability. But despite the large transfer sizes, programme effects do not last beyond the assistance cycle.

Refugees face unique challenges in any context, but they also share many of the same characteristics of the native poor, including uncertainty and high volatility in income and expenses, migratory transience, exclusion from formal credit, insurance, savings and labour markets, and daily mental and physical stressors.

Our results characterise a potential lower bound of the horizon on which effects of large cash-based interventions can be sustained, particularly when targeted at structurally excluded populations who lack access to supporting institutions and safety nets that protect against fall-backs.