In a nutshell

With multispeed recoveries, a tailored approach is necessary, with policies well calibrated to the stage of the pandemic, the strength of the economic recovery and the structural characteristics of individual countries.

Once the health crisis is over, policy efforts can focus more on building resilient, inclusive and greener economies, both to bolster the recovery and to raise potential output.

Even while all eyes are on the pandemic, it is essential that progress is made on resolving trade and technology tensions. Countries should also cooperate on climate change mitigation, on modernising international corporate taxation and on measures to limit cross-border profit shifting, tax avoidance and evasion.

It is one year into the Covid-19 pandemic and the global community still confronts extreme social and economic strain as the human toll rises and millions remain unemployed. Yet even with high uncertainty about the path of the pandemic, a way out of this health and economic crisis is increasingly visible. Thanks to the ingenuity of the scientific community hundreds of millions of people are being vaccinated and this is expected to power recoveries in many countries later this year.

Economies also continue to adapt to new ways of working despite reduced mobility, leading to a stronger-than-anticipated rebound across regions. Additional fiscal support in large economies, particularly the United States, has further improved the outlook.

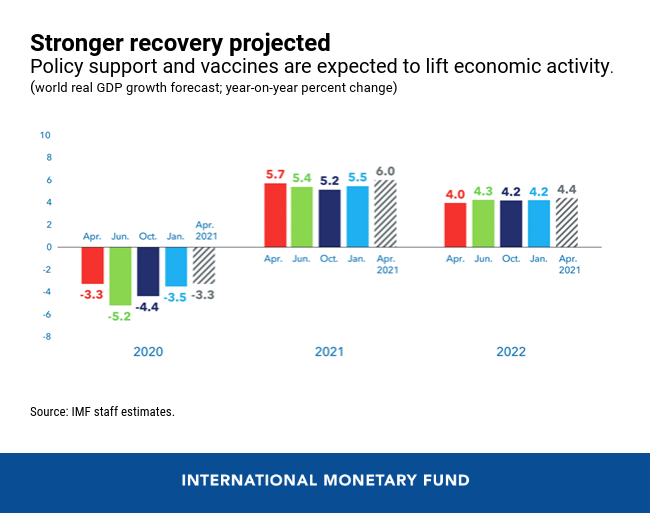

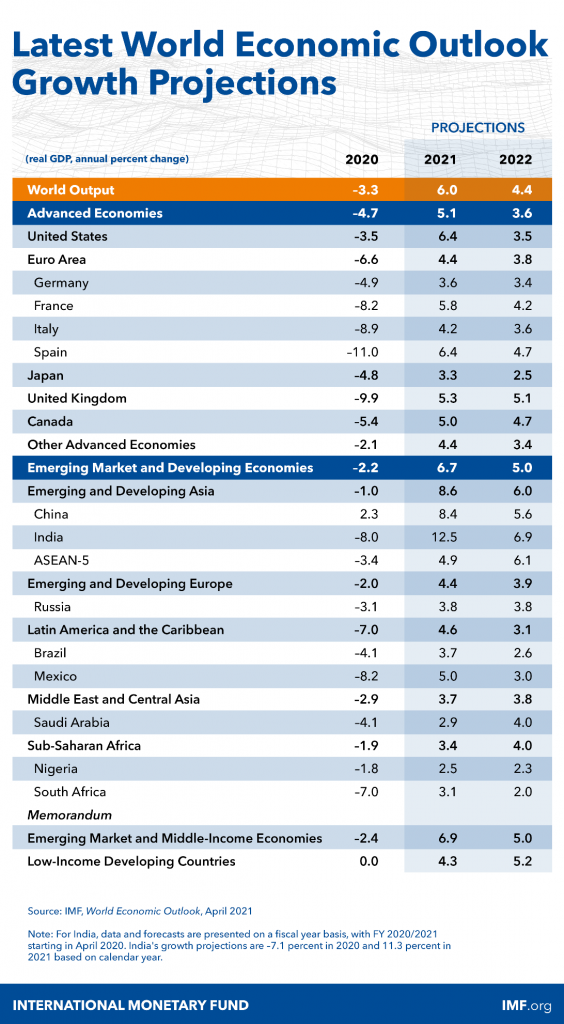

In our latest World Economic Outlook, we are now projecting a stronger recovery for the global economy compared with our January forecast, with growth projected to be 6% in 2021 (0.5 percentage point upgrade) and 4.4% in 2022 (0.2 percentage point upgrade), after an estimated historic contraction of -3.3% in 2020.

Nonetheless, the future presents daunting challenges. The pandemic is yet to be defeated and virus cases are accelerating in many countries. Recoveries are also diverging dangerously across and within countries, as economies with slower vaccine rollout, more limited policy support and more reliance on tourism do less well.

The upgrades in global growth for 2021 and 2022 are mainly due to upgrades for advanced economies, particularly to a sizeable upgrade for the United States (1.3 percentage points) that is expected to grow at 6.4% this year. This makes the United States the only large economy projected to surpass the level of GDP it was forecast to have in 2022 in the absence of this pandemic.

Other advanced economies, including the euro area, will also rebound this year but at a slower pace. Among emerging markets and developing economies, China is projected to grow this year at 8.4%. While China’s economy had already returned to pre-pandemic GDP in 2020, many other countries are not expected to do so until 2023.

Daunting challenges ahead

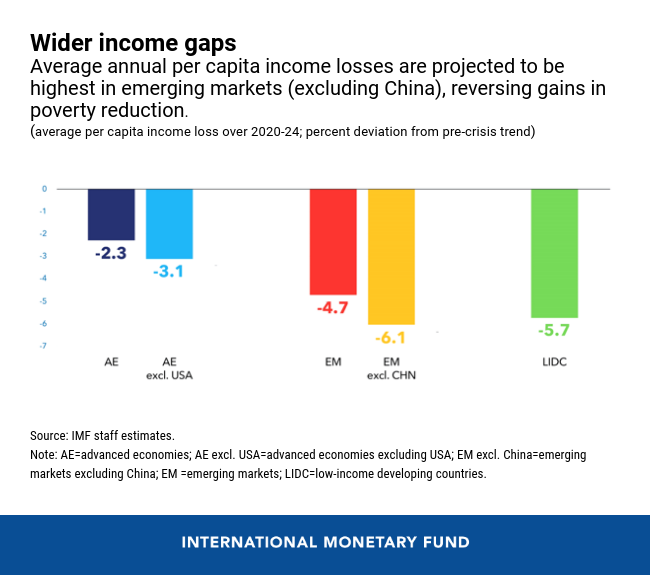

These divergent recovery paths are likely to create wider gaps in living standards across countries compared to pre-pandemic expectations. The average annual loss in per capita GDP over 2020-24, relative to pre-pandemic forecasts, is projected to be 5.7% in low-income countries and 4.7% in emerging markets, while in advanced economies the losses are expected to be smaller at 2.3%. Such losses are reversing gains in poverty reduction, with an additional 95 million people expected to have entered the ranks of the extreme poor in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic projections.

Uneven recoveries are also occurring within countries as young and lower-skilled workers remain more heavily affected. Women have also suffered more, especially in emerging market and developing economies. Because the crisis has accelerated the transformative forces of digitalisation and automation, many of the jobs lost are unlikely to return, requiring worker reallocation across sectors – which often comes with severe earnings penalties.

Swift policy action worldwide, including $16 trillion in fiscal support, prevented far worse outcomes. Our estimates suggest last year’s severe collapse could have been three times worse had it not been for such support.

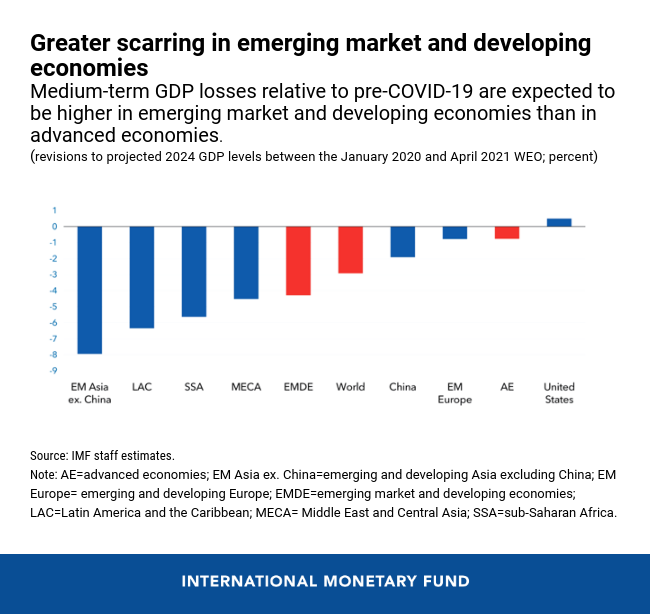

Because a financial crisis was averted, medium-term losses are expected to be smaller than after the 2008 global financial crisis, at around 3%. But unlike after the 2008 crisis, it is emerging markets and low-income countries that are expected to suffer greater scarring given their more limited policy space.

A high degree of uncertainty surrounds our projections. Faster progress with vaccinations can uplift the forecast, while a more prolonged pandemic with virus variants that evade vaccines can lead to a sharp downgrade. Multispeed recoveries could pose financial risks if interest rates in the United States rise further in unexpected ways. This could cause inflated asset valuations to unwind in a disorderly manner, financial conditions to tighten sharply and recovery prospects to deteriorate, especially for some highly leveraged emerging markets and developing economies.

Working together to give people a fair shot

Policy-makers will need to continue supporting their economies while dealing with more limited policy space and higher debt levels than prior to the pandemic. This requires better-targeted measures to leave space for prolonged support if needed. With multispeed recoveries, a tailored approach is necessary, with policies well calibrated to the stage of the pandemic, the strength of the economic recovery and the structural characteristics of individual countries.

Right now, the emphasis should be on escaping the health crisis by prioritising healthcare spending – on vaccinations, treatments and healthcare infrastructure. Fiscal support should be well targeted to affected households and firms. Monetary policy should remain accommodative (where inflation is well behaved), while proactively addressing financial stability risks using macroprudential tools.

As the pandemic is beaten back and labour market conditions normalise, support such as worker retention measures should be gradually scaled back. At that point, more emphasis should be placed on reallocating workers, including through targeted hiring subsidies and reskilling of workers.

As exceptional measures such as moratoria on loan payments are withdrawn, firm insolvencies could rise sharply and put one in ten jobs at risk in many countries. To limit long-term damage, countries should consider converting previous liquidity support (loans) into equity-like support for viable firms, while developing out-of-court restructuring frameworks to expedite eventual bankruptcies. Resources should also be devoted to helping children catch up on lost instructional time during the pandemic.

Once the health crisis is over, policy efforts can focus more on building resilient, inclusive and greener economies, both to bolster the recovery and to raise potential output. The priorities should include green infrastructure investment to help mitigate climate change, digital infrastructure investment to boost productive capacity and strengthening social assistance to arrest rising inequality.

Financing these endeavours will be more difficult for economies with limited fiscal space. In such cases, improving tax capacity, increasing tax progressivity (on incomes, property, and inheritance taxation), deploying carbon pricing and eliminating wasteful expenditures will be essential. All countries should anchor policies in credible medium-term frameworks and adhere to the highest standards of debt transparency to help contain borrowing costs and eventually reduce debt and rebuild buffers for the future.

On the international stage, first and foremost, countries need to work together to ensure universal vaccination. While some countries will get to widespread vaccinations by this summer, most, especially low-income countries will likely have to wait until end-2022. Speeding up vaccinations will require ramping up vaccine production and distribution, avoiding export controls, fully funding the COVAX facility on which many low-income countries rely for doses and ensuring equitable global transfers of excess doses.

Policy-makers should also continue to ensure adequate access to international liquidity. Major central banks should provide clear guidance on future actions with ample time to prepare, to avoid ‘taper-tantrum’ kinds of episodes as occurred in 2013. Low-income countries will benefit from further extending the pause on debt repayments under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative and operationalising the G20 Common Framework for orderly debt restructuring. A new allocation of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights will provide needed liquidity protection in highly uncertain times.

Even while all eyes are on the pandemic, it is essential that progress is made on resolving trade and technology tensions. Countries should also cooperate on climate change mitigation, on modernising international corporate taxation and on measures to limit cross-border profit shifting, tax avoidance and evasion.

Over the past year, we have seen significant innovations in economic policy and massively scaled-up support at the national level, particularly among advanced economies that have been able to afford these initiatives. A similarly ambitious effort is now needed at the multilateral level to secure the recovery and build forward better. Without additional efforts to give all people a fair shot, cross-country gaps in living standards could widen significantly and decades-long progress in global poverty reduction could reverse.

This article first appeared on the IMF blog here.