In a nutshell

Coronavirus containment measures (CCMs) have generally been effective in reducing the rate of contagion and thereby deaths; but their effectiveness of depends largely on the timeliness with which they were introduced and the type of measures adopted.

Restrictions on activities (closing school and workplaces, etc.) seem to be more effective than restrictions on personal liberties (lockdowns, bans on meetings, etc.); closing schools and workplaces have a particularly strong containment effect.

Countries with better healthcare systems and more democratic regimes tended to delay adoption of CCMs restricting individual liberties but adopted restrictions on activities in a timely fashion; while delays led to higher contagion rates, they did not necessarily lead to a higher number of fatalities.

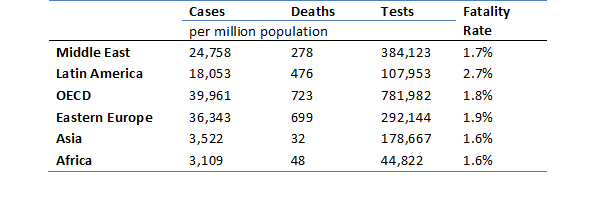

The pandemic has delivered a big hit to health and economic progress across the world – and the Middle East has not been an exception. Yet, as of mid-January 2021, the region had generally fared reasonably better than elsewhere in comparative terms. On average, the Middle East has seen around one-half of the cases (per million inhabitants) observed in the OECD or Western Europe, although significantly more than in Latin America. Asian and African data suffer from severe misreporting and cannot be directly compared.

More importantly, fatalities per million inhabitants and per case have been significantly lower on average in Middle Eastern economies. Testing, which is one key tool for controlling the disease, has been more widespread than in other emerging regions.

Of course, it should be acknowledged that these positive figures conceal significant heterogeneity among Middle Eastern countries and that country averages are influenced by the comparatively better stance of Gulf economies. Nevertheless, heterogeneity is also significant in other regions.

Table 1. Covid-19 cases, deaths, tests and fatality rate in 160 countries (unweighted averages)

Source: Worldometer webpage, accessed January 12, 2021.

Notes: fatality rate= deaths/cases. Data include 16 Middle East countries; 25 economies from Latin America; 30 OECD countries; 25 East European economies; 23 Asian countries and 41 African economies.

As the world grapples with the ‘second wave’ of a pandemic that has already claimed more than 1.5 million lives and affected over 90 million people globally, countries are being forced to renew lockdowns and social distancing measures. But how effective are these measures in containing the spread of Covid-19 – and how quickly should they be adopted?

In a recent study (Blanco et al, 2020), we use daily data from the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker database covering 158 countries over the period from January to August 2020 to address these questions empirically. We assess three dimensions of coronavirus containment measures (CCMs):

- We first identify the main factors that triggered the adoption of government CCMs.

- We then study the timing with which these measures have been adopted and discern which countries came early or late in responding to the Covid-19 outbreak.

- Finally, we assess the effectiveness of eight different CCMs in flattening the Covid-19 epidemiological curve and reducing contagion and fatality rates, controlling for other exogenous variables.

Assessing the effectiveness of CCMs requires addressing three issues. First, the number of cases and casualties tend to display high persistence, thereby necessitating the use of dynamic models. Second, countries are highly idiosyncratic in the unobservable features of their health systems and the characteristics of the population, indicating the existence of individual country effects. Third, reverse causation and endogeneity are very likely, since governments may decide to implement CCMs as a result of the evolution of the disease. We use dynamic panel data models with consistent instrumental variables estimators to address these issues rigorously.

Our econometric analysis suggests that, on average, CCMs have been effective in reducing the rate of contagion and thereby deaths. But the effectiveness of CCMs depends largely on the timeliness with which they were introduced and the type of measures adopted. Naturally, the effects in each country depend also on the compliance of the population with CCMs, as well as the measures being appropriately enforced by the authorities.

Our results also reveal differences in effectiveness across the variety of CCMs. Restrictions on activities (closing school and workplaces, etc.) seem to be more effective than restrictions on personal liberties (lockdowns, bans on meetings, etc.). In particular, closing schools and workplaces have a strong containment effect.

Adopting these CCMs would have reduced daily cases by around six to eight percentage points 14 days after their implementation. Interrupting public transport seems to have had no effect whatsoever on daily cases. Restrictions on personal liberties such as stay-at-home orders or banning meetings and public events would have reduced the rate of daily cases by five percentage points.

Our research shows that countries with better healthcare systems and more democratic regimes tended to delay the adoption of CCMs that restrict individual liberties but adopted restrictions on activities in a timely fashion. The delays led to higher contagion rates, yet not necessarily to a higher number of fatalities.

Importantly, our results also detect demonstration effects, as the early adoption of coronavirus containment measures in Western Europe led other countries to accelerate their adoption. Finally, our results show that while CCMs have been effective in reducing death rates, the capacity of health systems, in particular the ratio of Covid-19 cases to doctors and nurses, plays a critical role in reducing fatalities.

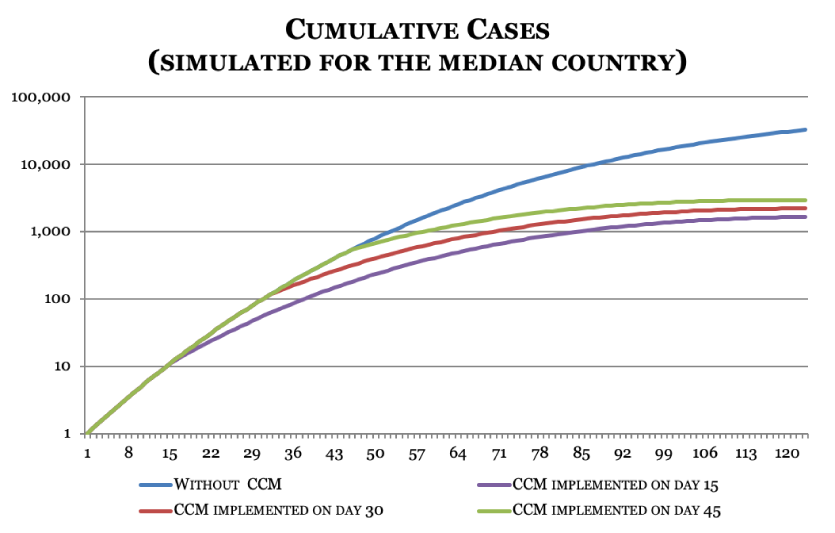

The reduction in contagion rates has a significant cumulative effect since the spreading of the disease directly depends on the prevalence of active cases in the population. Figure 1 shows, in a highly stylised fashion, the value of enacting the containment measure as well as the importance of the timing of adoption.

We use our econometric models to track the evolution of the disease. Without any containment policy, the number of cases reaches over 30,000 120 days after the outbreak of the first case of the disease. If CCMs are implemented early, the number of cases barely reaches 1,600. The median delay in the adoption of CCMs was around one month after the outbreak, in which case countries would have seen around 2,200 cases after four months. Late adopters would see around 3,000 cases.

Two forces are at play. On one hand, the CCM lowers the rate of growth of cases. On the other hand, the lower the number of cases, the smaller is the base for spreading the disease and the weaker is the dynamic effect embedded in the model. Both mechanisms reinforce each other and explain the significant differences in the number of cases when CCMs are implemented vis-à-vis the laissez-faire case.

Figure 1

Further reading

Blanco, Fernando, Drilona Emrullahu and Raimundo Soto (2020) ‘Do Coronavirus Containment Measures Work? Worldwide Evidence’, Policy Research Working Paper No. 9490, December, World Bank.