In a nutshell

Bets on the ability of OPEC+ producers – members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries plus Russia and nine others – to push oil prices much higher are unwarranted.

The history of OPEC’s attempts and failures to maintain the price of oil higher than warranted by demand and supply for any length of time offers a sobering lesson for governments of the Middle East.

As a larger and less homogenous group, OPEC+ will have a harder time in keeping its members to agreements about production cuts because it will not be able to make exit from the group costly.

The Covid-19 pandemic that engulfed much of the globe last spring wreaked havoc in the world oil market, reducing demand for oil by 10 million barrels per day (mbd), the largest drop in demand ever. By April 2020, oil prices were down by two-thirds, to less than $20 per barrel, while some futures markets briefly recorded a negative price.

The price collapse has naturally cost Middle Eastern economies billions of dollars every day. Both the oil-rich economies as well as those that receive remittances, investment, grants and contracts from them are suffering. To cope, the region’s governments have been downsizing and restructuring while they also fight the pandemic.

Even in the richest countries with large sovereign funds – Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – governments are cutting back on generous cash transfers and subsidies, and cancelling or putting on hold their ambitious, high profile projects, many of which face financing difficulties.

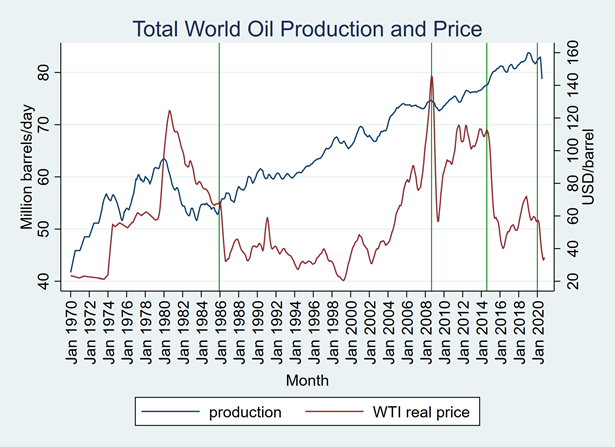

They are unwilling to run down their sovereign funds to maintain consumption standards in case the oil price recovery takes longer than a year or two. The last time a price collapse ended a decade-long oil boom was in 1986, after which oil prices did not recover until the early 2000s (see Figure 1). By the end of the decade, GDP per capita in Saudi Arabia and the UAE were half their values in 1980. A more judicious approach to downsizing may prevent a repeat experience, but it requires a reliable forecast of future prices.

Figure 1: The world price and production of oil

Note: Six-month moving averages of world output and the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price, deflated by the US Consumer Price Index.

Sources: US Energy Information Administration.

Forecasts of future prices focus on two divergent factors: how long will it take for demand for oil to recover; and how effective will be the agreement among the so-called OPEC+ producers (members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries plus Russia and nine others) in keeping supply at bay. True, the OPEC+ agreement in March 2020 did remove enough oil from the market to raise prices to above $40 per barrel, but, if economics and history are any guide, bets on the ability of the new group to push prices much higher are unwarranted.

This is because all voluntary collusive production agreements succumb to cheating sooner or later, and the record of such agreements in the past confirms this. A brief review of the history of OPEC’s attempts and failures to maintain the price of oil higher than warranted by demand and supply for any length of time offers a sobering lesson for governments of the region not to base their economic plans on OPEC+ doing what OPEC has not been able to do in the past.

The clearest lesson is from the 1986 price collapse. After nearly a decade of high prices, in the early 1980s, a global recession and substitution away from oil caused a gap of a few million barrels per day between demand and supply. The informal agreements that OPEC had operated with since its successful price hike of December 1973 proved inadequate to maintain the price. So, in 1982, Saudi Arabia, which had previously opposed the idea of production quotas, agreed to them in the hope of halting the loss of its market share.

Before 1982, they had seemed unnecessary because, as Cremer and Salehi-Isfahani (1989 and 1991) have argued, high prices had removed the incentive to sell more oil at the high price. With no excess supply, there was no need for collusive action.

But as Saudi Arabia would soon discover, quotas are necessary for setting limits for members’ production levels and for the group to maintain production discipline, but they are not sufficient. They do not stop cheating when prices are on a downward trajectory and there is no penalty for flouting their assigned quotas.

Saudi exports continued to slide, reaching one-third of their normal level in 1986. In an abrupt move, Saudi Arabia announced a price formula (called the ‘netback’) that set Saudi oil as the cheapest on the market, abandoning its role as the swing producer. Prices collapsed quickly and did not recover for a decade and a half.

Throughout the 1990s, OPEC stood by as the oil price fluctuated in the $40-50 range (in today’s dollars). In the fall of 1990, the price briefly rose to $70 following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. After the crisis was over a few months later, member countries expanded output in response to the higher price, forcing it back down. Since the price increase was widely considered to be temporary, it was difficult to prevent members from taking advantage of it. By 1998, prices had reached historic lows. It would take a strong and sustained increase in the global demand for oil, mainly from East Asia, to start the oil boom of the 2000s.

The big question for oil exporters is this. Now that the second oil boom is over, will the market be in the doldrums for one or more decades, or will OPEC+ succeed where its predecessor has failed?

Economic logic and historical experience say no. As a larger and less homogenous group, OPEC+ will have a harder time in keeping its members to agreements about production cuts because it will not be able to make exit from the group costly. To discourage future splits, the European Union had to make Brexit costly for the UK. Last June, Mexico, a signatory to the March 2020 agreement, announced that it would not abide by the group’s extended production cuts, effectively leaving the group with no penalty.

This suggests that for economic planners in oil-rich countries betting on global demand recovery is safer than on OPEC+.

With several vaccines on the way, the outlook for oil demand recovery is positive. The IEA (International Energy Agency) predicts that in 2021 half of the lost demand due to the pandemic – about 5.8 mbd – will be recovered.

But while demand may recover to some extent, prices may not because, as history shows, moderate price increases encourage more supply, bringing them back down.

The current agreement has maintained prices around the current level ($40-50 range), but it is not enough to raise them to levels that would end budgetary pressures in oil-rich countries. The so-called fiscal break-even price for Saudi Arabia for 2020 is estimated at around $78.

If collusive agreements are unlikely to bring back glory to the world oil market, spending plans in oil-exporting countries should focus on ways to reduce their break-even prices closer to $50. Such plans would not only allow for the possibility of a longer recovery time from the Covid-19 shock, but also for sluggish demand in the foreseeable future due to global environmental concerns.

Further reading

Crémer, J, and D Salehi-Isfahani (1989) ‘The rise and fall of oil prices: a competitive view’, Annales d’Economie et de Statistique (1989): 427-54.

Crémer, J, and D Salehi-Isfahani (1991) ‘Models of the oil market’, Fundamentals of Pure and Applied Economics 44, Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Press.