In a nutshell

The MENA region has fallen behind sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia in terms of statistical capacity; the differences between countries cannot be explained by lack of resources.

National statistics centres in most MENA countries were set up decades ago, so they have had enough time to build capacity; the dearth of adequate, accurate, reliable and timely data has to be explained by unwillingness to share information.

The absence of quality data prevents policy-relevant domestic analysis and assessment by international institutions; loss of public trust in decision-making and policy announcements leaves the way for misinformation, discouraging foreign investors.

The recent World Bank report on how transparency can help the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is long overdue as are the reforms to address the problem (Arezki et al, 2020).

In this column, I first will go through the evidence that supports the report’s main claims about ‘the chronic low-growth syndrome’, the concomitant disappointing and high unemployment, and the unsustainable fiscal deficits and debt.

Second, I will offer an explanation for the puzzling evidence of how, over the years, the MENA region fell behind sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia in terms of statistical capacity and the differences between countries in this regard cannot be explained by lack of resources.

Third, I will elaborate more on why data transparency matters, what should countries do, especially as it relates to the Covid-19 crisis, and how the Bretton Woods institutions – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank – can help.

Rising prices in resource-scarce countries are due mainly to imported inflation

Macroeconomic imbalances have constrained international reserves in resource-scarce countries, forcing exchange rate adjustments. Further, depreciating currencies explain most of the increase in the price of tradables.

Moreover, weaknesses in agriculture and inadequate supply chains lead to pressures on food prices, amid rising demand. In many cases, subsidies have helped rein in price increase, but threaten fiscal sustainability, as they tend be untargeted.

In general, expansionary fiscal and monetary stances have further contributed to inflationary pressures.

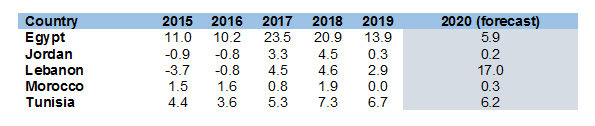

Inflation rates in resource-scarce countries – consumer price index (CPI) change (%)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database

Low inflation in GCC countries is mostly due to the peg to dollar

Given the peg to the dollar in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), imported inflation is aligned to international inflation, minus any appreciation of the dollar. More recently, the appreciating dollar has helped to contain inflationary pressures.

Large government subsidies, in many cases, keep prices of food and energy in check. Against the backdrop of lower oil price and slower economic activity inflationary pressures have eased. Prices of non-tradables remain subdued or even declining in case of excess supply, particularly for housing.

Recent monetary easing in the GCC countries is determined by the orientation of the Fed’s policies, which started last year, but accelerated more recently to counter the effects of Covid-19. Thus far, there is no noticeable inflationary impact against the backdrop of lingering slowdown in economic activity.

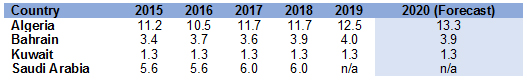

Inflation rates in resource-rich countries – CPI change (%)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database

Sluggish growth is due to weak fundamentals in non-oil countries

Structural impediments have hampered growth prospects despite expansionary policies in resource-scarce countries. Protection measures in key sectors, pervasive intervention by the state and loss of investor confidence have resulted in protracted low growth in many non-oil countries. This was further compounded by weak competition due to lack of effective modern competitiveness laws.

Further problems are evident in the ineffective bureaucracy in investment and export promotion agencies, which resulted in underdeveloped high value added activities such as high-tech exports and specialised services. In general, uncertainty and instability in some countries deter domestic and foreign investors in non-oil countries.

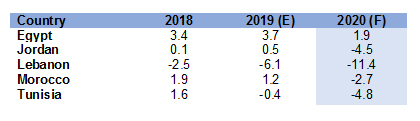

Real GDP per capita growth (%)

Source: World Bank. E: Estimate. (F): Forecast

Low non-hydrocarbon growth in resource-rich countries has limited diversification prospects

Growth in oil-rich countries has been constrained recently by hydrocarbon activities that are dependent on available resources and commitments to OPEC quotas. For a long history, ample oil revenues have provided countries little incentives for diversification, resulting in ‘after-oil’ strategies being still lagging.

While the business environment and competitiveness are, in general, better than in non-resource rich countries, challenges remain in education, productivity and institutions, and inadequate human capital.

Real GDP per capital growth (%)

Source: World Bank. E: Estimate. (F): Forecast

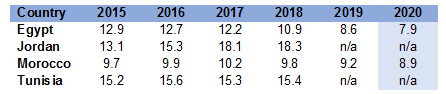

High and chronic unemployment in resource-scarce countries

Sluggish growth, weak private sector activity, low productivity and skills gap limit job opportunities in resource-scarce countries. High unemployment among youth and mostly university graduates is due to mismatch between education and job market requirements. Skill shortages are common in many sectors, testament to inadequate public education and vocational training schemes.

Unemployment rates – percentage of total labour force

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Unemployment in some resource-rich countries contrasts with job opportunities available to expatriates

Limited job opportunities for nationals in the private sector in some GCC countries are due to lack of diversification, skill mismatch, and the limited role of the private sector.

Further, constraints on the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) limit their role as an engine of job creation.

Moreover, education systems have resulted in a mismatch between public school curricula and the requirements of the private sector employment. The local population generally prefers public sector jobs (as they are less demanding and more generous).

Unemployment rates in resource-rich countries – percentage of total labour force

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

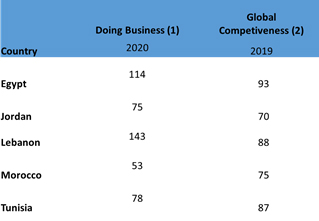

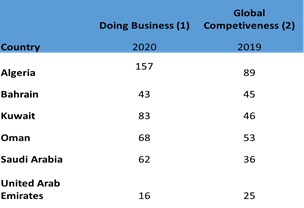

In general, non-resource-rich countries and Algeria rank low in global competitiveness, which defeats their export-oriented strategies

High and unsustainable fiscal deficits in non-resource rich countries limit the fiscal space and spill over to external imbalances

Large and chronic fiscal deficits in resource-scarce countries are due to the dominant role of the state in the provision of public services like education and health. Further, the government has committed to untargeted price subsidies of food and energy and subsidies to state-owned enterprises.

Attempts at fiscal consolidation have failed due to hesitant reforms and strong opposition from interest groups benefiting from the status quo. Moreover, the absence/underdevelopment of local debt markets leaves no choice but to borrow from the banking sector, and/or issue debt in international markets to finance the widening fiscal deficit.

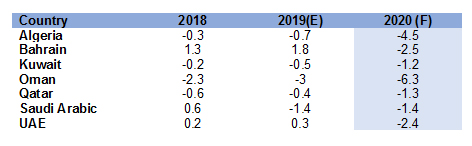

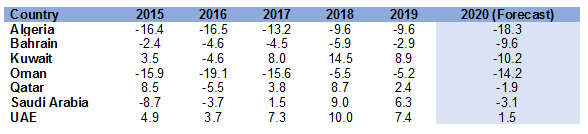

Fiscal deficit – percentage of GDP

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Despite oil revenues, fiscal deficits have become more common among resource-rich countries

The persistent decline in the oil price has been a wake-up call given the high share of oil revenues in the budget of many resource-rich countries. Expansionary fiscal policies have been the drivers of economic growth, due to developmental needs, social pressures for subsidies, and limited role of the private sector.

Governments’ easy access to debt and ample oil revenues encouraged fiscal dominance. Moreover, the absence/underdevelopment of local debt markets leaves no choice but to issue debt in international markets or borrow from banks.

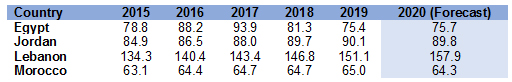

Fiscal deficit in resource-rich countries – percentage of GDP

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Unsustainable current account deficits in resource-scarce countries

The external current account deficit is related to the fiscal deficit (the so-called twin deficits). The trade deficit in resource-scarce countries is due to limited high value added exports and high dependency on imports for energy, food, equipment, etc. Variable exports of agricultural and food products constrain diversification of the export structure and limit the value added component of exports. Fluctuations in commodity prices increase vulnerabilities of exports with global growth and the spillovers to the domestic economy.

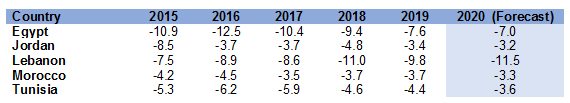

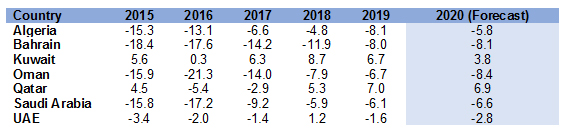

The current account of the balance of payments – percentage of GDP

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

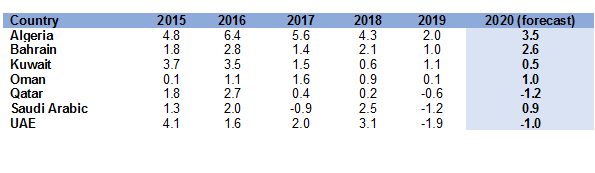

External deficits in Algeria, Bahrain and Oman add to the macroeconomic fragilities in these countries

In resource-rich countries, the current account deficit is linked to the fiscal deficit and large imports, coupled with fluctuations in hydrocarbon prices. Some countries can afford a double-digit deficit as it can borrow against stream of future oil and gas income.

The current account surplus was an opportunity to use foreign currency receipts to finance development and diversify economies away from high dependency on hydrocarbon resources. More recently, with the decline in the oil price, many resource-rich countries are projected to have a current account deficit and lose international reserves.

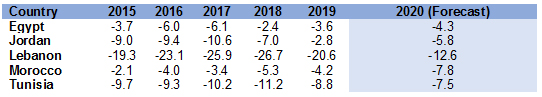

Current account balance in resource-rich countries – percentage of GDP

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Looming crisis for MENA? Rising debt fuelled by non-sustainable fiscal deficits and capital outflows

Research has established that when ‘gross external debt reaches 60% of GDP, a country’s annual growth declines by 2%’ as the debt service obligations tend to choke off resources away from growth. Hence, net public debt is considered ‘a crucial metric to assess sustainability’.

In many MENA countries, the ratios point to high and unsustainable public debt. While the current situation of negative interest rates may ease the burden of debt overhang, many countries have faced rising external debt to be paid in appreciating dollar while their natural resources of foreign income have dwindled.

The exception may be resource-rich countries, which have better access to the international market given their low public debt ratio (net public debt to GDP: 13.7% in Saudi Arabia, 40.7% in Algeria and 44.9% in Oman in 2020).

General government net debt – percentage of GDP

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Lack of data transparency and why it matters for growth and competitiveness

In terms of statistical capacity, there are large discrepancies between countries; and the region as a whole is falling behind East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The World Bank Statistical Capacity Index shows huge discrepancies between countries, with considerable lag for some countries like Tunisia, Lebanon and Morocco compared with Egypt.

Disparity across countries in the region and the fact that the MENA region is behind other regions cannot be explained by lack of resources. The evidence signifies lack of interest in data dissemination and transparency may be the reasons behind the observed data opacity. Even in resource-rich countries, investment in data capacity has been lagging against anti-transparency sentiments.

Statistical Capacity Score (Overall Average), 2018

Source: World Bank

Statistical capacity-building is not an issue

National statistics centres in most countries were set up decades ago, so they have had enough time to build capacity. But the dearth of adequate, accurate, reliable and timely data has to be explained by unwillingness to share information (in many instances, available results from censuses and surveys took long time to be published).

Labour data may be embarrassing to disseminate as it will show high and rising unemployment: Out of 16 MENA countries, only 4 use ILO definition for employment, for most other countries the definition is unspecified. Public debt data may be problematic with creditors and international investors, constraining access to international markets. Some population data may also be resisted (such as data on expatriates in some GCC countries).

Transparency matters for data-based research and decision-making

The absence of quality data prevents policy-relevant domestic analysis and assessment by international institutions. Weak research capacity in MENA, aggravated by data opacity, leaves no choice but to resort to ad hoc uninformed decisions that may constrain policies. Loss of public trust in decision-making and policy announcements (even if true) leaves the way for rumours and misinformation, discouraging foreign investors.

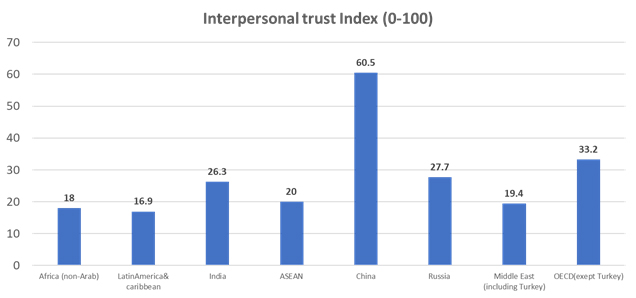

Interpersonal trust is very weak in MENA compared with India and China

Source: Kuran (2016)

Lack of trust can have important implications on development

It can plausibly be argued that much of the backwardness in the world can be explained by the lack of mutual confidence, which is aggravated in the absence of quality data on a regular basis. Lack of trust inhibits impersonal market forces, leaving personal connections as the only thing that matters for businesses securing a government licence or public procurements, as an example. The generalised economic inefficiencies hinder Middle East development.

Covid-19 repercussions: an opportunity to reform

Non-resource-rich MENA countries were among the first to apply for IMF/World Bank emergency funding in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and its severe implications on available funding. In the context of these programmes, countries will be attentive to requests in terms of data transparency.

Many reforms are dependent on data availability. For example, data disclosure to reduce leakages are crucial elements to design successful targeted transfers. This kind of data disclosure can serve as a basis for targeted transfers to replace the hugely inefficient food subsidies, as an example.

Such reforms and policy measures can trigger a long overdue reform of micro and macro statistics overhaul, including collection, processing and timely publication of economic, social and sectoral data, using internationally accepted definitions and methodology.

To address youth unemployment, investing in data capacity would help to introduce professional training programmes for information sharing with substantial contribution from the government, as an example, which can be expanded indefinitely to capitalise on the comparative advantages of the talented youth.

MENA countries need to get serious about long overdue far-reaching data transparency and data-based analysis reforms

The way forward should lay the foundations for upgraded national statistics centres with better resources to implement key strategic initiatives. The goal is to invest in data collection using internationally accepted definitions and methodology, especially for unemployment, government budgets and debt.

In addition, capacity-building should include the conduct of micro data surveys on job market and firm level activity, for example, the World Bank Enterprise Surveys. Data availability will encourage policy relevant data based economic research towards the development of independent and well-resourced national economic research centres/think tanks, including partnership with internationally renowned economic think tanks for training and joint research projects.

What can international institutions do?

As international organisations are likely to become strategic partners in the region to avail necessary funding and steer the course of necessary reforms after the pandemic, data quality and transparency should be given a premium. The IMF/World Bank should include data transparency as part of regular consultations with member countries (for example, IMF Article IV Consultation and access to special financing, etc.).

Technical assistance missions should sponsor quality data collection and surveys with national statistics centres and regional networks like ERF and the Arab Monetary Fund. The goal is to publish the results when ready to give incentives to other member countries to do the same. Of priority is to give more focus and incentives for member countries to graduate from enhanced general data systems to the more advanced specialised data systems.

The payoff for data availability and quality has been proven in terms of market access and cost of credit, as it was shown that the spread on new bond issues declined by 75 basis points following subscription in specialised data systems (IMF, 2005). In parallel, data transparency should be integrated as part of the IMF/World Bank conditionality for programme countries.

In the wake of Covid-19, orderly sovereign debt restructuring would be most facilitated for MENA countries who apply for it and tie it to data transparency and quality as it would help foster investors’ confidence and boost international reputation. Covid-19 provides an opportunity to integrate short-term challenges into the long-term reform agenda so that MENA countries can graduate from the current crisis to a better and sustainable path of growth and prosperity.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

IMF(2005) ‘Does SDDS Subscription Reduce Borrowing Costs for Emerging Economies?’, IMF Staff Papers 52(3): 1-6.

Kuran, Timur (2016) ‘Trust, Cooperation and Development: Historical Roots’, lecture at Duke University.