In a nutshell

Regardless of how it is measured, the Arab region is the only one in the world where money metric poverty was on the rise before Covid-19.

The pandemic only amplifies an existing trend of rising poverty caused by strategic choices made by Arab countries during the past four decades.

Covid-19 provides (yet another) wake-up call for Arab countries to rethink their social contracts and economic development strategies.

On 1 April, a policy brief from the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) used country-level GDP growth projections as of mid-March to estimate that an additional 8.3 million people would fall into poverty by 2021 in Arab countries, excluding the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries (ESCWA, 2020).

A more recent ESCWA technical study (Abu-Ismail, 2020) provides the technical details for this estimation, but also reassesses the poverty impact in 14 non-GCC low- and middle-income Arab countries using (significantly lower) growth forecasts released by the United Nations (UN) on 14 April. These are the main assumptions, results and policy conclusions:

Assumptions

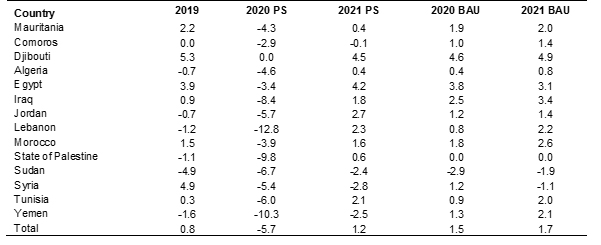

As in all other regions, growth forecasts are dim. According to the most recent estimates by the UN World Economic Forecasting Model (WEFM), GDP per capita in these 14 Arab countries is projected to decline by 5.7% in 2020 before rebounding to a modest 1.2% in 2021. While it is harder to justify from available data, there is also an expectation that the Covid-19 will lead to a slight deterioration in the distribution of income.

Key results

Compared with the pre-Covid-19 ‘business as usual’ growth scenario, this massive negative growth shock, as well as a presumably slight negative distributional shock, is expected to leave an additional 16 million people in poverty using national poverty lines and an additional nine million people in extreme poverty (measured here as earning below the $1.9 per day poverty line).

Policy conclusions

These results, daunting as they may be, are not unexpected given what we know about the root causes and drivers of poverty, inequality and vulnerability in the region. The current pandemic only accentuates the impact of existing structural deficiencies embedded in ‘rentier’ economic and governance systems that have shaped poverty and inequality outcomes in this region for the past four decades. It is not their fundamental cause.

In fact, regardless of how it is measured, the Arab region is the only one where money metric poverty was on the rise before Covid-19. One telling indicator is the number of poor using nationally defined poverty lines, which jumped from 66 million in 2010 (22.8% of the population of the 14 countries in 2010) to 101 million in 2019 (30%).

The difference between the baseline number of poor in the 1 April policy brief of 93 million poor and the 101 million reported here is due to adopting the PPP (purchasing power parity) equivalent of the value of the most recent national poverty lines even in conflict affected countries for better cross-country comparability. For Syria and Yemen, this implies using pre-conflict poverty lines of $3.5 and $2.7 per day, respectively, which significantly inflates the poverty rates compared with the $1.9 poverty line, which was applied in ESCWA (2020).

The silver lining is that this pandemic provides (yet another) wake-up call for Arab countries to rethink their social contracts and economic development strategies.

High vulnerability to poverty and large growth shock in 2020: brace for impact

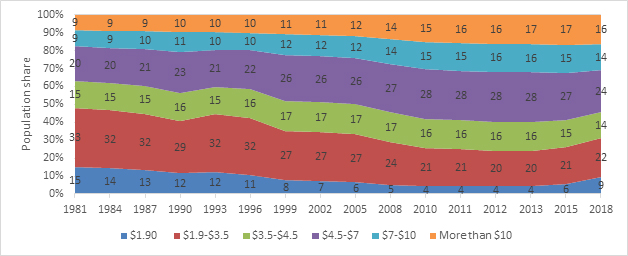

A large share of the population in Arab countries earns between $1.9 per day, which is a common measure of extreme poverty, and $3.5 per day, which is closer to the value of national poverty lines (22% in 2018). An equally large share of the population lies just above the latter (14% of the population in 2018 earning between $3.5 and $4.5 per day, as in Figure 1).

The implication is that even minor shocks to the income of these vulnerable households will have a relatively higher impact on extreme poverty compared with other developing regions. This is also reflected in the higher poverty elasticities for Arab countries at these poverty lines.

Figure 1: Distribution of population (%) across expenditure groups (expenditure per capita per day in US$, 2011 PPP) in 14 Arab countries, 1981-2018

Source: Aggregated results for 14 countries included in Table 1 based on World Bank PovcalNet, accessed 9 June 2020.

Table 1 summarises the growth story. In the pre-Covid-19 or ‘business as usual’ scenario, GDP per capita in the 14 Arab countries was expected to grow by 1.5% and by 1.7% in 2020 and 2021, respectively. While not significant in comparison with fast-growing Asian economies, this growth rate may have led to some modest poverty reduction. But with a projected scenario indicating a decline of 5.7% in their GDP per capita in 2020, all the 14 countries are now plunged into negative growth territory and four economies are expected to continue contracting in 2021.

Table 1: GDP per capita growth in 2019 and in the projected (PS) and ‘business as usual’ (BAU) scenarios, 2020-2021

Source: Authors estimates based on UN forecasts (released on 14 April 2020) using the World Economic Forecasting Model (WEFM)

Limitations

Given the high vulnerability to poverty, a growth shock of this magnitude is likely to produce a negative impact on the region’s headcount poverty rates and number of poor. The question is: how strong will this impact be? But before answering this question, a few remarks on the limitations of the methodology to bear in mind when interpreting the results.

As a recent World Bank column on The Forum noted (Aziz et al, 2020) the frequency and quality of household income and expenditure surveys in the region are notoriously poor, and their unit record data are not always accessible for many countries. This forces any exercise to impute poverty measures based on grouped data from surveys that are sometimes over a decade old (as in the case of Syria).

In addition to data constraints, assumptions about the choice of poverty line and the expected growth and distribution outcomes at the household level, which are needed to undertake projections, may entail a great deal of arbitrariness and speculation.

On the first of these limitations, research on poverty and inequality measurement is ripe with evidence to support the conclusion that poverty measurement approaches remain without universal acceptability. In an ideal world, household surveys would be designed the same way across countries and over time to allow for a consistent and comparable poverty measure.

In the real world, household surveys and poverty definitions are designed at the national level, and poverty lines can be set at the national, regional or global levels for heterogeneous reasons and using heterogeneous approaches. To accommodate these different objectives and perspectives, the headcount poverty results in ESCWA (2020) are presented at both national and international poverty lines.

Still, as emphasised in Abu-Ismail (2020), the results from the national poverty lines are the most relevant to evaluate the impact of the current pandemic since they provide a more meaningful lens through which both policy-makers and the lay person can view and relate to the incidence of money metric poverty. Moreover, as they are nationally owned and defined targets, policy-makers are held accountable to their results.

A second major limitation relates to the high uncertainty in growth forecasts that are being continuously revised. But even if one accepts the validity of these growth rates at the national level, there remains much speculation in assuming a commensurate impact on households. This is perhaps the most controversial hypothesis of the entire exercise given that there has been a large and growing divergence between growth outcomes at the national level and at the household level in many middle-income Arab countries over the past two decades.

A third limitation is that no one really has an idea how the Covid-19 crisis will affect inequality. Although the Covid-19 crisis is expected to affect all income groups, the lower earning group may be more directly and significantly subjected to income losses as they have a larger share of their heads employed in informal service sector activities that are strongly affected by the current recession. Low earning households are also less able to rely on their savings and wealth to smooth consumption during the current crisis relative to higher income households.

Thus, Abu-Ismail (2020) conservatively assumes that the current crisis will lead to a mild increase in the population-weighted Gini: from 32.9 % in 2018 to reach 34.9% in 2021 for the 14 countries under this assessment with an acknowledgement that this may only reflect the best-case scenario in the actual change in income distribution.

Of course, as noted in a recent report on rethinking inequality in Arab countries (ESCWA, UN and ERF, 2019), the actual Gini of Arab countries when factoring in the missing top earners may be much higher.

Regardless of how it is measured, money metric poverty is a major challenge

The results here are reported using national and international poverty lines. For the former, headcount poverty ratios were computed based on the most recent value (in 2011 PPP) and for the latter, the $1.9 and $3.5 poverty lines were adopted as poverty yardsticks. The former is used in monitoring Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 (it is also a reasonable proxy for extreme poverty) and the latter is the population-weighted average value of the national poverty lines for the 14 Arab countries in the study.

There are three main results.

First, regardless of the choice of poverty line, poverty was on the rise in the Arab region even before Covid-19. The population-weighted average for the 14 non-GCC countries based on growth performance is 29.2% in 2019, which is equivalent to 101.4 million people. In 2010 the regional headcount poverty ratio using these same lines was significantly less, at 22.8%, or 66.4 million people.

Likewise, the regional headcount poverty ratio for the $1.9 poverty line more than doubled from 2010 to 2019, which is far more than the increase using the $3.5 (which rose from 25.3% to 30.9%) or national poverty lines (which rose from 22.8% to 29.4%). These results are easy to interpret given the impact of conflicts in Syria and Yemen.

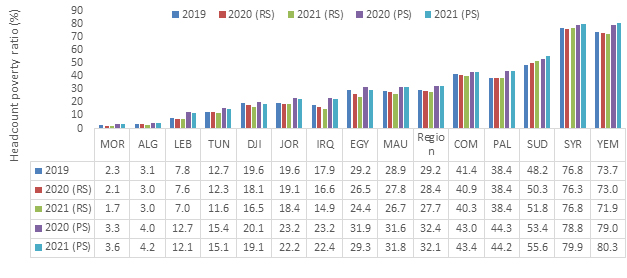

Figure 2: Headcount poverty projections in 2019 and for the reference (RS) and projected (PS) growth scenarios using national poverty lines, 2020-2021

Source: Abu-Ismail (2020)

Second, the impact on headcount poverty is expected to be significant in 2020, but it stabilises in 2021. The regional headcount poverty ratio in the projected growth scenario (PS) rises to 32.4% in 2020, but then falls slightly to 32.1% in 2021 (Figure 2).

This realisation of this scenario brings the total number of poor in the 14 countries to 116 million in 2021, the bulk of whom (over 80%), reside in four countries: Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Sudan. Under the reference (or ‘business as usual’ pre-Covid-19) growth scenario (RS), which assumes growth process would lead to higher household income and consequently to poverty reduction, the regional headcount poverty ratio is lower, at 27.7% (or 100 million poor people).

The poverty impact, which is the difference between both these scenarios, is equivalent to a 4.4% rise in the headcount poverty ratio by 2021, equivalent to an additional 16 million people. The result based on the $3.5 PPP poverty line (which is the population-weighted average of the national poverty lines for the 14 countries) is quite similar with an estimated additional poor population of 15.7 million.

Third, the region is not on track to meet the SDG target indicator 1.1, which aims to reduce the $1.9 headcount poverty ratio by half by 2030. The study not only shows the region is off-track on this indicator from 2010 to 2019, but also that the pandemic is expected to have a stronger relative impact on Arab countries compared with the impact from national poverty lines. Accordingly, the projected regional headcount ratio reaches 11.7% in 2021, equivalent to 42.2 million people, which is 9.1 million higher than in the ‘business as usual’ reference scenario.

Concluding remarks

Long before the current crisis and even before 2010, the region had witnessed many serious development challenges, in particular related to the lack of sustainability in and over-reliance on natural resource rents, poor productivity growth and high youth unemployment. Concurrently, occupation, conflicts and political instability have also led to widespread human suffering, which has risen since 2010, with strong negative impacts on the region’s vulnerable and middle-class population.

In this context, poverty headcount trends witnessed from 2010 till 2019, daunting as they may be, are not surprising. The pandemic only amplifies an existing trend of rising poverty caused by strategic choices made by Arab countries during the past four decades.

As argued by ESCWA and ERF (2019), these choices related to the orientation of their economic policies and nature of their systems of governance have produced enduring structural effects. The main result of the exercise: that 16 million additional persons are expected to fall in poverty by 2021, is but one of the many manifestations of these structural deficits.

Be that as it may, any results regarding poverty in the region should be considered with caution given the many limitations related to data, growth assumptions and choice of poverty measurement methodology.

One important concluding remark to emphasise in this regard is that the whole purpose of this projection exercise is to get a reasonable estimate of the order of magnitude of the potential poverty impact rather than a precise forecast. A precise forecast would not be possible without conducting further and more detailed microsimulation analysis of national household surveys (that is neither available nor accessible in many of the 14 countries).

Finally, there is always hope. Even with the region’s poor now approaching one-third of its population, there are still many feasible mitigating policy options. In fact, as argued in another recent study (Abu-Ismail and Hlasny, 2020), with its current wealth levels, the region should raise the bar higher and aim for poverty eradication. This of course is practically impossible as a target to achieve, but Arab countries, especially the middle-income ones, have the means to get close if there is political will, sensible social and economic policies, strong institutions and fair governance practices.

Further reading

Abu-Ismail, Khalid (2020) ‘Impact of Covid-19 on Money Metric Poverty in Arab Countries’, ESCWA.

Abu-Ismail, Khalid, and Vladimir Hlasny (2020) ‘Wealth inequality and the cost of poverty reduction in Arab countries: the case for a solidarity wealth tax’, ESCWA.

ESCWA (2020) ‘Mitigating the impact of Covid-19 on poverty and food security in the Arab region’, E/ESCWA/CL3.SEP/2020/Policy Brief.2

ESCWA, UN and ERF (2019) ‘Rethinking Inequality in Arab Countries’, Report E/ESCWA/EDID/2019/2.

Atamanov, Aziz, and World Bank colleagues (2020) ‘Measuring monetary poverty in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: Data gaps and different options to address them,’ The Forum ERF.