In a nutshell

Data transparency is crucial for formulating optimal policies, expanding the frontier of knowledge and building trust with civil society – particularly in a time of global pandemic.

Data capacity and accessibility in the Middle East and North Africa fell between 2005 and 2018; in 2018, the region had the lowest score measured by the World Bank’s statistical capacity indicator.

The fall in statistical capacity may have resulted in a loss of GDP per capita in the region of 7-14%.

The global Covid-19 pandemic has necessitated revisiting longstanding debates on recurring challenges in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The vulnerabilities in the social contract are once again exposed.

To confront this epidemic, citizens and their governments need to draw on depleting reservoirs of trust, which can only be replenished through greater transparency. A radical call for openness and transparency may be the only way to revive the relationship between governments and their citizens that has been on the rocks for quite some time.

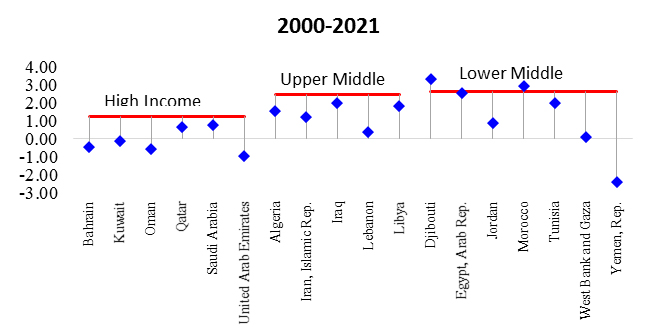

The recurring challenges in the region have manifested themselves in the form of chronic low growth that has been persistent for decades. MENA countries have been underperforming relative to their peers across the world. When per capita growth for each country since the beginning of the twenty-first century into the forecast horizon is compared to the typical (median) economy with similar levels of development, most MENA economies fall short (see Figure 1).

Growing faster than the typical economy is a mediocre benchmark at best – and yet is one that the MENA region fails to achieve. A rough calculation suggests that if all MENA economies met this benchmark, the region would be, on average, at least 20% richer than it is today.

Could lack of data capacity and transparency be partially responsible for low growth? This hypothesis is explored in our recent report (Arezki et al, 2020).

Advanced economies have modern and well-coordinated data collection systems that are accessible to the research community. Many economies in the MENA region have either lagged in their capacity to generate data or they have prevented the research community, the independent media and civil society from accessing the data. While concerns over privacy are real, little attention has been paid to the costs of opaque data systems that hamper external knowledge generation.

Figure 1: Chronic low growth in the MENA region

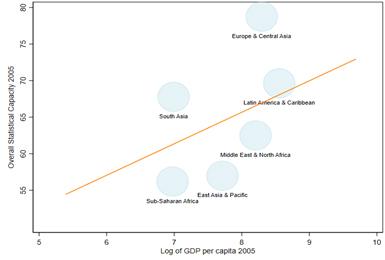

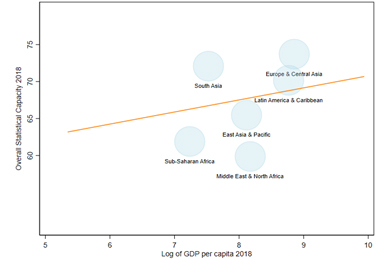

The state of data transparency and reliability in MENA is wanting. Since 2005, MENA was the sole region to document a decline in ‘statistical capacity’, a term that includes aspects of data transparency as well as reliability. By 2018, the MENA score was the lowest of all regions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The fall in statistical capacity in the MENA region

Note: The overall statistical capacity (SCI) measure captures availability and periodicity of micro data (micro and administrative), adherence to international standards in terms of methodology, and periodicity and timeliness of socio-economic macro indicators. The fitted line between overall statistical capacity and the level of development is based on 149 mostly developing economies. The circles represent the regional averages.

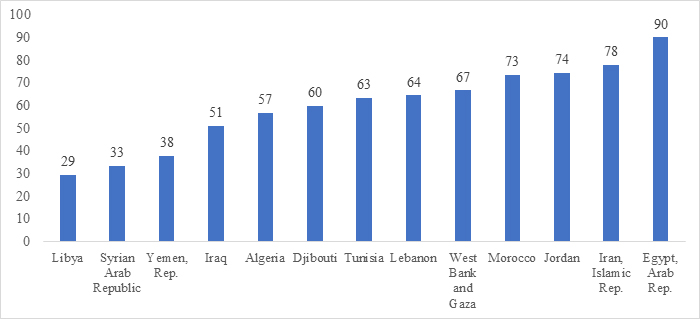

There are considerable differences in data transparency and reliability among the countries in the MENA region (see Figure 3). Egypt is the best performer, followed by Iran and Jordan. Data transparency and reliability has been steadily increasing since 2005 in these economies.

At the other end are Libya, Syria and Yemen. All three economies are overwhelmed by conflict and their data systems have drastically deteriorated since 2005. Nonetheless, even in the seemingly high performers, deterioration in freedom of expression has probably become an impediment to harnessing the upside from the production of reliable data.

Figure 3: Statistical capacity score in the MENA region in 2018

There are three plausible ways in which data capacity and transparency can help economies grow.

First, credible and timely data serve as the basis for policy formulation and reforms. Policies can only be as good as the empirical evidence on which they are based. At a fundamental level, data are about records.

Take the example of a business. A manager has the primary goal of raising profits. To achieve this, performance must be benchmarked historically and compared to that of competitors. Collateral must be evaluated and leveraged to obtain financing to pursue new ventures. Risk and reward must be balanced. Investors need to be enticed. Data are essential to achieve these goals.

Second, data that are accessible to the broader civil society can generate better policies and reforms as hypotheses are tested, debated and disputed so that only the best ideas survive.

Third, when data are of questionable quality or unavailable, the gap between perceptions and reality may grow. The credibility of governments is likely to fall, and thus even when governments adopt good reforms, the public may be sceptical. The result may be economies that are more prone to social upheaval.

Preliminary evidence suggests that there may be a positive correlation between statistical capacity and subsequent economic growth during the period 2005-18, for a sample of 146 economies. The findings stand even after taking account of several important predictors of growth. The decline in the statistical capacity index experienced in the MENA region between 2005 and 2018 may have resulted in a loss of GDP per capita of between 7% and 14%, depending on the econometric model employed.

These findings are preliminary, and several caveats apply. Future research may put these findings in more solid empirical footing.

Bridging MENA’s data transparency gap requires a multi-pronged approach. The pandemic has put this issue at the forefront. Where governments lack the capacity to generate data, investments are needed to build that capacity. Where governments are unwilling to share data, agreements need to be developed in concert with a clear agenda that highlights the crucial role of data in generating good policies and social harmony.

The immediate goal is to bring the data transparency challenge to the table. Future initiatives will dig deeper into these issues, acknowledging country-specific contexts.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly El-Mallakh, Nelly, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam, Ha Nguyen and Marwane Zouaidi (2020) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Das, Jishnu, Do Quy-Toan Do, Karen Shaines and Sowmya Srikant (2013) ‘U.S. and Them: The Geography of Academic Research’, Journal of Development Economics 105: 112-130.

Islam, Roumeen (2006) ‘Does More Transparency Go along with Better Governance?’, Economics and Politics 18(2): 121-67.

Kubota, Megumi and Albert Zeufack (2020) ‘Assessing the Returns on Investment in Data Openness and Transparency’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9139.

Register to attend our upcoming live webinar on Long-term growth and data transparency on May 13, 2020 at 4:00 pm Cairo Local Time.