In a nutshell

There do not seem to have been political cycles in local government budgets in Turkey since the AKP came to power in the early 2000s.

There is evidence of notable economic differences across regions based on their political affiliations, including state-owned banks lending more in politically competitive provinces during local election years if the provinces are already allied with the AKP.

There may be more subtle ways than the opportunistic use of public budgets for the government to improve its chances of re-election, including credit, tax treatment and judicial processes.

Voters’ approval of political candidates tends to fluctuate in line with local and national economic outcomes. If voters place more weight on recent developments than distant periods, then incumbent politicians may have strong incentives to manipulate policy around election times to improve their chances of re-election. Such electioneering – or ‘opportunistic political cycles’ – may result in periods of economic expansion and contraction that follow electoral cycles.

In a chapter in a recent ERF book, we delve into the issue of election cycles in the context of the recent political history of our native Turkey (Bircan and Saka, 2019a). In particular, we focus on a period that has been characterised by the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) coming to power in 2002.

Since then, the AKP has retained a majority of the seats in the Turkish parliament through successive general elections. Yet it has faced increasingly tougher competition in local elections, owing in part to the Turkish electorate’s tendency to judge mayoral candidates not only based on their party affiliation but also on their relative economic performance in office.

We conjecture that this aspect of Turkish politics has given incentives to the ruling party to put an increasingly larger emphasis on winning local elections. Hence, in our analysis, we focus on the existence of local (instead of general) election cycles by using the heterogeneity in terms of political affiliation and competition across the full set of Turkish provincial municipalities. We first focus on the possibility of cycles in local government budget figures.

Even though there is some historical evidence that there were fiscal cycles in Turkey before the 2000s (Asutay, 2004), the use of the government budget in such an opportunistic way may have been restricted during the AKP’s term due to two main reasons:

- First, the fiscal discipline imposed following the twin crises of 2001 and the accompanying stand-by agreements with the International Monetary Fund limited the resources for the government to engage in politically motivated spending.

- Second, the AKP has used its better fiscal performance (relative to previous governments) as one of the most important selling points to its voters who had been tired of the soaring public debt and resulting financial crises of the past.

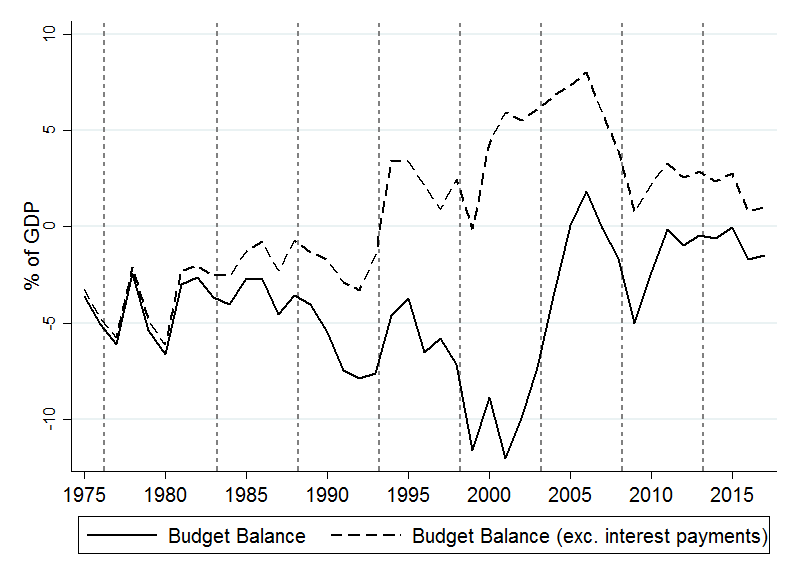

Figure 1 illustrates this point that fiscal discipline returned to Turkey only after the early 2000s, coinciding with the AKP coming to power.

Figure 1: Gross public sector budget balance in Turkey since mid-1970s

Source: Bircan and Saka (2019a); Turkish Ministry of Development.

Notes: This figure illustrates the evolution of the budget balance (as a percentage of GDP) of the Turkish public sector, with and without interest expenditures, between 1975 and 2017. The public sector balance is comprised of the consolidated budget, state economic enterprises, local authorities, revolving funds, social security institutions and extra-budgetary funds. Horizontal axis denotes year-ends. Dashed vertical lines correspond to local elections.

In line with the view that the economic governance of the country no longer supported the opportunistic use of public budgets, we fail to find an identifiable trend in differences in local government spending across Turkish municipalities of different political affiliations.

Following Akhmedov and Zhuravskaya (2004), we additionally test for different types of budgetary expenditures such as capital investments, purchasing of goods and services, and the employment cost of public workers. If politicians are motivated to adjust public spending to gain popularity with voters, then we would expect them to increase public sector employment and boost local economic activity prior to elections.

But we do not detect any politically motivated trends in spending on these local budget items in our econometric exercises. There do not seem to have been political cycles in local government budgets in Turkey during this recent period.

Given the limited space for fiscal manoeuvring and the increasing importance of the Turkish banking industry in spurring growth since early 2000s, there is reason to believe that election cycles may have instead taken a financial form. In this spirit, we went on to test for the existence of lending cycles in Turkish state-owned banks by analysing the credit volumes broken down by province and aggregated by bank type (state vs. private) over 15 years between 2003 and 2017 (Bircan and Saka, 2019b).

We find that state banks, compared with private banks, lend more in politically competitive provinces during local election years, but only if the province is already allied with the AKP prior to the election. In the opposition regions, such rewarding behaviour takes the form of punishment in the sense that state banks decrease their lending relative to private banks in the politically contested areas prior to the local elections.

We also detect that this behaviour is more prevalent in corporate credit rather than in consumer credit, pinpointing local job creation and credit-induced growth as the ultimate targets for the government. This can have sizable aggregate outcomes, as we also document that the credit constraints most affect provinces and industries with high initial efficiency.

Lastly, in our book chapter, we analyse a firm-level survey recently undertaken in a representative sample of Turkish provinces and show the preferential effects on firms of being located in the AKP’s strongholds rather than in the opposition side.

Such advantage seems to exist not only in terms of objectively measured credit market conditions, but also in terms of firms’ perceptions of how they get treated across various government policies, such as tax audits and judicial processes. Although it is impossible to infer causality from such simple comparisons across provinces, it assures us that there are notable economic differences across regions based on their political affiliations.

Overall, we believe that the current state of research on election cycles should take account of the nature of the economic governance in developing countries, which may imply more subtle ways for the government to improve its chances of re-election. Credit, tax treatment and judicial processes could be only a few of many such potential mechanisms.

Further reading

Akhmedov, A, and E Zhuravskaya (2004) ‘Opportunistic political cycles: Test in a young democracy setting’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(4): 1301-38.

Asutay, M (2004) ‘Searching for opportunistic political business cycles in Turkey’, unpublished draft.

Bircan, C, and O Saka (2019a) ‘Elections and economic cycles: What can we learn from the recent Turkish experience?’, in Crony Capitalism in the Middle East edited by I Atiyas, I Diwan and A Malik, Oxford University Press.

Bircan, C, and O Saka (2019b) ‘Lending cycles and real outcomes: Costs of political misalignment’, EBRD Working Paper No. 225.