In a nutshell

The MENA region could be the hardest hit by what is arguably a perfect storm: the coronavirus spreading to the region and oil prices collapsing – in a region already raked by social discontent and massive street protests.

It is likely that lower oil prices will directly hurt oil exporters (whose income will decline) and indirectly hurt importers (who will see reduced foreign direct investment, remittances and grants from the exporters).

The battle against the coronavirus and its economic consequences will be complicated by empty government coffers: the region will need much international support to help it navigate an extremely rough patch.

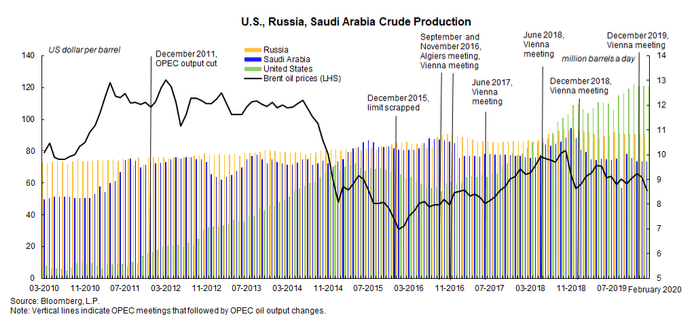

In November 2014, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) decided to maintain output despite a perceived global glut of oil. The result was a steep decline in price.

Two years later, in November 2016, OPEC took a different route and committed to a six-month, 1.2 million barrel-a-day (mbd) reduction in crude oil output. The result was a small price increase and some price stability. But the respite was to be temporary, because the price increase stimulated other oil production that could come online quickly, primarily from shale in the United States (see Figure 1).

On 5 March, OPEC proposed a 1.5 mbd production cut for the second quarter of 2020, of which 1 mbd would come from OPEC countries and 0.5 mbd from non-OPEC but aligned producers (most prominently Russia). The following day, Russia rejected the proposal, prompting Saudi Arabia – the world’s largest oil exporter – to boost production to 12.3 mbd, reaching its full capacity. Saudi Arabia also announced unprecedented discounts of almost 20% in key markets.

Figure 1: The rise of shale and the OPEC put

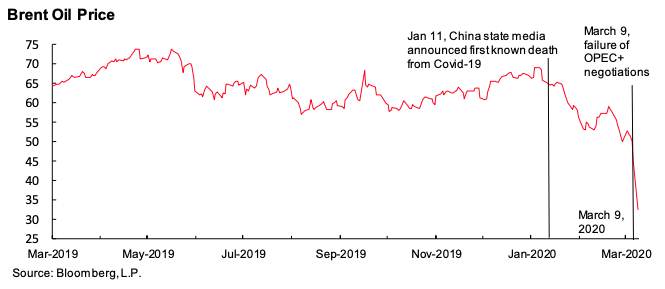

The result was a more than 30% plunge in prices, to as low as $31.1 per barrel on 8 March (see Figure 2). The upward pointing futures curve suggests the market still expects oil prices to recover slowly – and to reach $50 per barrel by the end of 2024. That said, as we assess the stance of the different protagonists in this month’s oil war and the response of shale production, it seems clear that the futures curve is likely to shift.

COVID-19 and uncertainty about oil demand

Following the discovery of the new virus and infections in China at the beginning of 2020, oil prices had declined by about $20 a barrel until the end of last week – in anticipation of reduced oil demand as widespread COVID-19 infections depressed output (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The 2020 oil collapse

Indeed, as authorities in China shuttered production facilities as part of their efforts to contain the spread of the virus, oil demand from China dropped significantly. The Oil Market Report from the International Energy Agency underscores the importance of China’s role in oil consumption (IEA, 2020). China accounts for 14% of global oil demand and for more than 80% of global growth in demand in 2019.

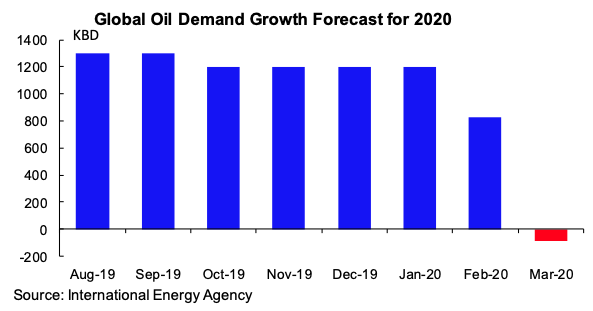

The newly released report forecasts that in 2020, global oil demand growth will fall for the first time since 2009. The 0.09 mbd demand decline in March is 1.1 mbd lower than the forecast made in February, which already was well below the forecast made in January (see Figure 3). The IEA expects global demand for oil to fall by 2.5 million barrels per day year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020.

Figure 3: Erosion of demand prospects

Indeed, because of China’s increasingly important role in the global economy, any setbacks to its economy are expected to hurt the rest of the world significantly. The global fear and uncertainty regarding the spread of virus is likely to hurt investment decisions in China and other countries, further weighing on demand prospects and lowering oil prices.

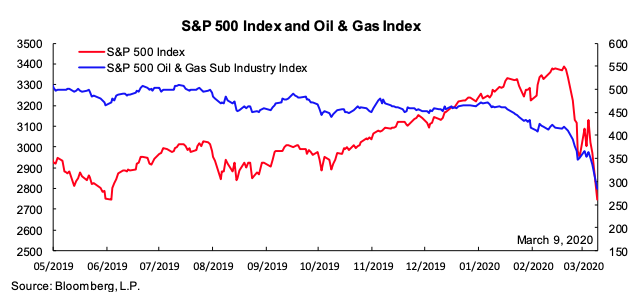

Figure 4: Financial markets roiled

The collapse in oil prices roiled financial markets already nervous about the spread of the novel coronavirus. Equities in the United States and the rest of world lost about 7% (see Figure 4). Shares in US shale companies were hardest hit, with some shale stocks losing 30-50% of their value. But a decline in oil stocks overall signals the market perceptions of a persistent drop, and that the oil price war will affect higher-cost production the most.

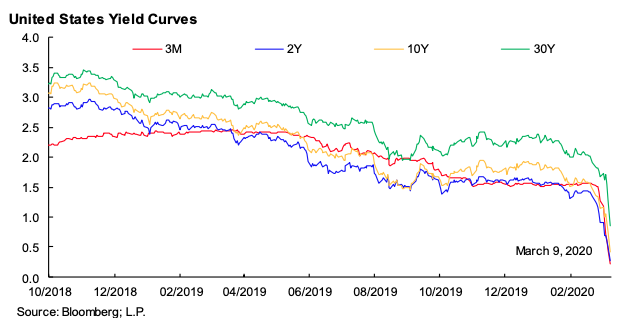

Moreover, US government bond yields moved to historical lows (see Figure 5), while the VIX – a measure of market volatility – hit its highest levels since the financial crisis more than a decade ago. These moves suggest that investors have a heightened fear of recession and have intensified a search for safety.

Figure 5: Flattening yield curve

Economic and social effects

As the world struggles with the fear of recession, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) could be the hardest hit by what is arguably a perfect storm: the coronavirus spreading to the region and oil prices collapsing. This in a region already raked by social discontent and massive street protests.

As of 11 March, Iran had reported over 8,000 infections and at least 291 deaths. The rapid rise in infections there is likely to disrupt the country’s production and trade. As the virus spread, the Iranian authorities closed schools and cancelled art and film events, and neighbouring countries closed their land borders with Iran.

Other MENA countries have also reported infections. As of 11 March, the United Arab Emirates had reported 74 cases, Iraq 71, Bahrain 110 and Kuwait 69. Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and West Bank and Gaza, all have also reported COVID-19 infections.

The ability to contain the virus depends on the strength of the public health systems of the MENA countries. The World Health Organization ranks most MENA countries relatively high among the world’s 191 health systems (Tandon et al, 2000) – with a few exceptions, such as Yemen (ranked 146th) and Djibouti (ranked 170th).

But some MENA countries might face difficulties containing the virus. For example, wars in Syria and Yemen will almost certainly impede the proper functioning of the health systems in both countries.

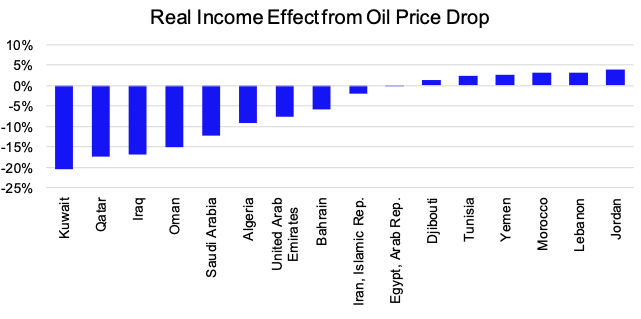

As a rule, lower oil prices are good for oil-importing countries and bad for oil exporters. A simple way to get a sense of the size of the real income effect is to multiply the difference between production and consumption (net oil export) as a share of GDP by the percentage point increase in the oil price (see Figure 6).

For example, based on a hypothetical assumption that oil prices were to stay 48% below the 2019 level, Kuwait – where net oil exports account for 43% of GDP – would experience a decline in real income of about 20% of GDP. For the same increase in price, Morocco would experience an increase in real income equivalent to 3% of GDP.

Figure 6: Back-of-the-envelope effect from the oil collapse

But in MENA, it is likely that lower oil prices will directly hurt oil exporters (whose income will decline) and indirectly hurt importers (who will see reduced foreign direct investment, remittances and grants from the exporters). Some countries, such as those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, still have buffers and should use them. Other oil-exporting countries, such as Algeria and Iran, are exhausting their buffers and will have to rely on flexible exchange rates to manage the current situation and conduct much-needed reforms in private-sector development and broader economic transformation.

But in MENA, it is likely that lower oil prices will directly hurt oil exporters (whose income will decline) and indirectly hurt importers (who will see reduced foreign direct investment, remittances and grants from the exporters). Some countries, such as those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, still have buffers and should use them. Other oil-exporting countries, such as Algeria and Iran, are exhausting their buffers and will have to rely on flexible exchange rates to manage the current situation and conduct much-needed reforms in private-sector development and broader economic transformation.

Among oil net importers such as Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt, a recession will contribute to already high levels of public debt.

The battle against the spread of the novel coronavirus and its economic consequences will be complicated by empty government coffers. The region will need much international support to help it to navigate an extremely rough patch.

Further reading

IEA – International Energy Agency (2020) Oil Market Report – March 2020.

Tandon A, CJ Murray, JA Lauer and D Evans (2000) ‘Measuring overall health system performance for 191 countries’, World Health Organization, Geneva.

This column was first published at Vox.