In a nutshell

The rate of childhood stunting in Egypt is high relative to countries in the MENA region with similar levels of economic development.

The number of Egyptian children who are stunted is changing over time due to changes in the rates of malnutrition and illness; but stunting is not only a result of biological factors, but also of economic, behavioural and cultural factors.

Better policies targeted at reducing illness and improving nutrition by increasing mothers’ employment, access to healthcare and sanitation are potential means to reduce childhood stunting in Egypt.

Childhood stunting is a serious health problem in Egypt. In 2014, one in five Egyptian children under the age of five were stunted, meaning that they were short for their age. That amounts to 2.1 million individuals, the largest number of stunted children in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

The stunting rate in Egypt is higher than in other low- to middle-income countries and is similar to that of low-income countries. For example, Egypt and Jordan have similar Gross National Incomes, but the average stunting rate in Egypt in the period 2005-2016 was almost three times that of Jordan: 22.3% in Egypt and 7.8% in Jordan (United Nations Children’s Fund et al, 2016).

Understanding the determinants of stunting in Egypt, which has unusually high stunting rates relative to its economic development and is changing drastically over time, merits investigation, particularly given the very high health and economic costs associated with stunting. Stunting, also known as linear growth retardation, is a long-term outcome of malnutrition, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), malnutrition is one the largest threats to public health (WHO, 2018a).

Globally, malnutrition accounts for almost 45% of child mortality and almost three million children under the age of five die per year as a result of malnutrition (WHO, 2018b; Global Panel, 2016). Stunted children who survive suffer from cognitive/psychological problems. An observed reduction of 2-3% of GDP demonstrates the combined economic, health and social costs associated with childhood stunting in Egypt (Onis and Branca, 2016; USAID, 2017).

Trends in stunting in Egypt

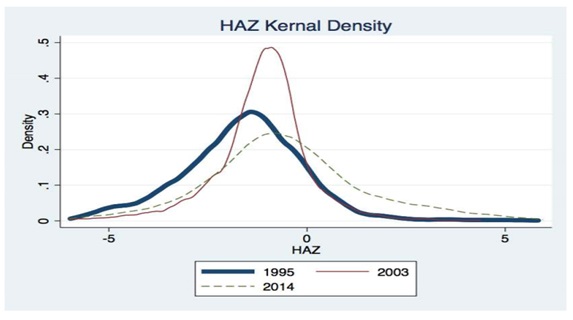

Over the last two decades, the height-for-age Z score (HAZ) distribution and stunting rates in Egypt have changed markedly. The HAZ is a standardised measure of children’s height. A child is stunted if their HAZ is under two standard deviations below the WHO median. A HAZ of 0 implies that the child has the WHO median height of children.

Figure 1 depicts the HAZ density for Egyptian children aged 2-4 in the years 1995, 2003 and 2014. The figure shows that the stunting rate was highest in 1995, reaching 35.6%. By 2003, the stunting rate has been reduced by almost half, reaching 16.7%. Surprisingly, that decline did not persist and the stunting rate increased to 20.5% in 2014.

The factors that led to changes in the HAZ distribution and stunting rates in Egypt over time remain unknown. My research (Hashad, 2019) uses data from Egypt’s Demographic and Health Survey for the years 1995, 2003 and 2014 to identify factors that are correlated with the change in the height of children aged 2-4. I try to identify the determinants of children’s nutritional status in Egypt over time in order to provide policy advice.

Pathogenesis of stunting

Despite the high global prevalence of stunting, the pathogenesis underlying stunting is surprisingly poorly understood (Prendergast and Humphrey, 2014). According to the WHO, stunting is a long-term, cumulative outcome that occurs due to chronic or recurrent undernutrition, chronic illness, psycho-social deprivation and poor maternal health (WHO, 2018b).

Stunting is attributed to medical (proximate) and socio-economic (distal) factors. There are three proximate factors that determine a child’s height: maternal height (genetics), illness and nutrition.

Besides these three proximate factors, there are other distal factors that contribute to stunting as they are correlated with the main factors. These distal factors include access to healthcare, place of residence, socio-economic status and education among mothers (WHO, 2018).

Based on this conceptualisation of stunting and the factors that affect height, my analysis relies on characteristics that have both a medical (proximate) and socio-economic (distal) impact on stunting. These include children’s characteristics, mothers’ characteristics, households’ socio-economic status (SES) and access to healthcare. Children’s characteristics include gender, age and where they reside.

To account for maternal factors, my research uses data on mothers’ height and weight. Measures of households’ SES include mothers’ employment status, mothers’ education, household wealth and sanitation. The last category of characteristics is access to healthcare and is a measure of whether mothers have ante-natal care during pregnancy by visiting a doctor or nurse (or no ante-natal care), and the number of ante-natal visits.

Results

Descriptive statistics show that there have been significant changes in mothers’ characteristics during the period of study. Compared with 1995, there was a significant decline in the fraction of underweight women and a significant increase in the fraction of women who are overweight and obese. Being underweight is a proxy for malnutrition, hence the decline in the fraction of underweight women implies that there is an improvement in mothers’ nutrition over time.

There has been minimal change in mothers’ height. There has been a significant decline in children with diseases, improved mothers’ nutritional status, more ante-natal care, improvement in water and toilet facilities, and an increase in the number of people who live in urban areas.

More in-depth analysis shows that the HAZ distribution and stunting rates can be attributed to changes in nutrition and illness. The reasoning is that the proximate causes of stunting are mothers’ height, illness and malnutrition.

The data show that the distribution of mothers’ height is not changing over time, hence I rule that out as the factor associated with the change in stunting over time. Due to data limitations, illness and malnutrition are not accounted for. Hence, illness and malnutrition are unobservables that are correlated with both HAZ and the distal factors of household wealth, employment, education, access to healthcare, region and sanitation.

This indicates that changes in the distal causes of stunting led to the change in the HAZ distribution through changes in illness and malnutrition. Therefore, the changes in illness and malnutrition over time could be potential factors driving the change in stunting. In addition, I look at socio-economic inequalities in health, and find that stunting is higher among families of lower SES.

Policy recommendations

Luckily, stunting is reversible. A stunted child can catch up, which means that for a given time period, the child can grow at a faster-than-expected rate for their age, which enables him or her to overcome their previous accumulated height deficit.

Previous research suggests that among children older than two years, there is catch-up (IFPRI, 2015). Catch-up occurs if the environment in which a child lives improves through health-related interventions or better nutrition. But if a stunted child remains in the same living conditions when he or she was stunted, there will be little or no chance of catching up (IFPRI, 2015).

To improve the environment in which children live to reduce stunting rates in Egypt, policies should be targeted towards increasing household income by increasing mothers’ employment and education. In addition, improving sanitation and access to healthcare can reduce illness and malnutrition and, consequently, stunting.

This is consistent with evidence that the improvement in socio-economic conditions of poor rural households improved children’s health status, and that economic growth in Egypt is an effective tool to lower child malnutrition and improve health. (Gummerson, 2011; Sharaf and Rashad, 2016). It is also suggests that allocation of wealth and resources across different households could lead to huge differences in HAZ and stunting rates.

Finally, stunting is a major threat to public health, affecting 2.1 million Egyptian children in 2014. There is no ‘one size fits all’ policy that will eradicate the problem as stunting is not only a result of biological factors, but also of economic, behavioural and cultural factors. Better policies targeted at reducing illness and improving nutrition by increasing mothers’ employment, access to healthcare and sanitation are potential means to reduce childhood stunting in Egypt.

Further reading

Global Panel: United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization and World Bank (2016) ‘UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates’.

Gummerson, Elizabeth (2011) ‘Moving on Up? Migration, Urbanization and the Dissolution of the Urban Health Advantage in South Africa’, Elsevier.

Hashad, Reem (2019) ‘Changes in Height-for-Age of Egyptian Children 1995 to 2014’, ERF Working Paper No. 1357.

IFPRI (2015) ‘Once stunted always stunted? What’s up with catch-up growth?’

Onis, Mercedes, and Francesco Branca (2016) ‘Childhood stunting: a global perspective,’ Maternal and Child Nutrition.

Prendergast, Andrew, and Jean Humphrey (2014) ‘The stunting syndrome in developing countries’, Pediatrics and International Child Health.

Sharaf, Fathy and Ahmed Rashad (2016) ‘Economic Growth and Child Malnutrition in Egypt: New Evidence from National Demographic and Health Survey’, Social Indicators Research.

USAID (2017) ‘The 1000 day window of opportunity: Technical guidance brief’.

WHO (2018a) ‘Egypt – Nutrition’.

WHO (2018b) ‘Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition. The Z-score or standard deviation classification system’.