In a nutshell

While the Gulf crisis seems to be cooling, it remains unclear whether signs of re-engagement are going to lead to a full restart in links between Qatar and its blockading neighbours.

The diplomatic crisis has created a new Gulf with no winners; it has further divided the Arab and Muslim world, and forced small states to make tough choices.

Qatar’s response to the blockade shows remarkable resilience and rapid and efficient adaptation, with the crisis accelerating Qatari plans and strengthening the country’s motivation to pay close attention to self-sufficiency.

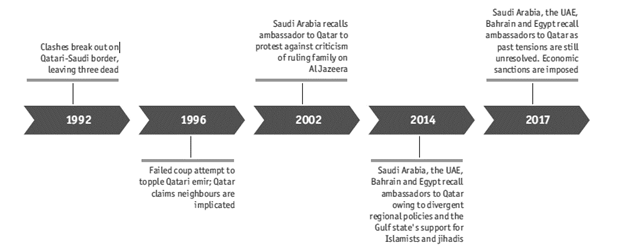

Qatar’s crisis with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf neighbours has decades-long roots (see Figure 1). The anti-Qatar bloc has long considered Qatar as too friendly to Iran, too provocative in its backing of the Al Jazeera media network and too supportive of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Although a variety of issues have been raised against Qatar, the most potent has been a strong feeling of annoyance in the Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) over Qatar’s support for Islamist movements. In addition, there is competition for leadership between Qatar and the UAE as the region’s biggest financial hub.

These developments put pressure on the Gulf region as an enduring political and security alliance, which became tangible in a diplomatic crisis in 2014. The collective decision by Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE to cut diplomatic and economic ties with Qatar on 5 June 2017 is the most recent flare-up in a series of long-running tensions between Qatar and its Gulf neighbours.

The recent crisis will escalate tensions between the protagonists in the region, which is, by its nature, very unstable. The crisis has rattled nerves, sending shockwaves around the world. It may cost the countries involved billions of dollars by slowing trade, investment and economic growth as they struggle with lower oil prices.

Figure 1: The origins and course of the 2017 Gulf crisis

While significant attention has been devoted to analysis of the effects of economic, macroeconomic and financial uncertainty on international business, rather less attention has been paid to the economic implications of geopolitical risks. The vast majority of these studies indicate that the unstable political scene can have a significant impact on stock markets, portfolio allocation and diversification opportunities. Some recent studies indicate that Qatar crisis has a significant impact on stock markets’ dependence and risk spillovers (Al-Maadid, 2019a, 2019b; Charfeddine and Refai, 2019).

The contribution of our research (Bouoiyour and Selmi, 2019) is three-fold:

- First, we compare the conditional volatility process of the stock markets of Qatar and the boycotting countries before and after the blockade.

- Second, we test whether this Gulf crisis has exacerbated the volatility spillovers across the region.

- Third, we assess the direction of spillover effects between various markets in an effort to identify the net transmitters and net receivers of risk spillovers. This should be useful for both portfolio risk managers and designers of policies aimed at safeguarding against increased political uncertainty surrounding the 2017 Gulf crisis.

Our analysis shows that while Qatar has been shaken by this crisis, the other countries are have not been unscathed, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE. All the stock markets become more volatile in response to the blockade, but such volatility does not persist.

Our findings also document that profound political instability over the Qatar crisis has moderately exacerbated stock market volatility transmission across Qatar and the boycotting countries. We then identify which stock market has the most impact in exporting volatilities to the other countries during the boycott of Qatar.

Before the boycott, there are two groups of countries: Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are viewed as volatility transmitters, whereas Bahrain and Egypt are considered to be risk receivers. After the crisis, we keep the same groups of countries, although with changing intensity of volatility spillovers.

Overall, our findings suggest that the boycott did not achieve the expected outcome. The fact that Qatar, Saudi Arabia and UAE responded in the same way (with respect to volatility persistence and the directional risk spillovers) to this crisis can be considered as a sign that Qatar ‘beat’ the boycott. Doha has demonstrated resilience in times of heightened political uncertainty. Despite its economic vulnerability, Qatar has successfully resisted the Saudi embargo.

How was Qatar able to face a blockade imposed on it by four countries with substantial traditional authority?

Qatar has often been aware of its vulnerability and has managed its business with dexterity (multiplying foreign partners, strengthening the management of gas resources and pursuing investment mediation) despite the economy’s reliance on the hydrocarbon sector. Qatar has retained the crown of world’s top exporter of liquefied natural gas in 2017, underpinning Qatari cash flow.

The financial reserves at the disposal of the authorities provide additional support. If needed, the authorities would place a particular emphasis on accelerating structural reforms to ensure that the economy remains internationally competitive and attractive for investment.

The diplomatic tensions have served as a catalyst for improving domestic food production and reducing reliance on other countries. In response to the rift, Qatari authorities brought forward some structural reforms in an attempt to stimulate the business environment. They plan to set up special economic zones, which would help to spur diversification opportunities and encourage foreign direct investment.

Overall, if this blockade showed the resilience of Qatar’s economy, it also underscores the incapacity of the boycotting countries to bring it down.

Why has the anti-Qatar quartet failed in its mission?

Saudi Arabia’s young leadership vowed to design comprehensive and transformative reforms that include a large range of socio-economic reforms. The latter have already started to address some of the country’s longstanding issues including, among others, enabling women to drive and initiating a value added tax. Furthermore, the Saudi leadership has undertaken reforms that are indispensable for economic diversification from the oil sector, such as labour market reform, privatisation and opening the market to foreign investors.

Even though the Saudi reform plans are vital for the future socio-economic stability of the kingdom, Saudi leadership has faced multiple socio-economic challenges in order to implement economic diversification policies. The Saudi authorities have taken initiatives in an attempt to attract foreign investors, such as launching an active privatisation programme and easing requirements for foreign institutional investors.

Nevertheless, such initiatives have not had the desired impact on attracting more inflows of foreign investment a cornerstone of the Saudi vision 2030 plan to diversify the economy away from its reliance on oil revenues. The kingdom’s bid to attract billions of dollars investment to build vast city developments has also been tarnished by Khashoggi affair.

Further reading

Al-Maadid, A, GM Caporale, F Spagnolo and N Spagnolo (2019a) ’Political Tension and Stock Markets in the Arabian Peninsula’, International Journal of Finance and Economics.

Al-Maadid, A, GM Caporale, F Spagnolo and N Spagnolo (2019b) ‘The Impact of Business and Political News on the GCC Stock Markets’, Research in International Business and Finance.

Bouoiyour, Jamal, and Refk Selmi (2019) ‘Arab Geopolitics in Turmoil: Implications of Qatar-Gulf crisis for Business’, ERF Working Paper No. 1337.

Charfeddine, L, and H Al Refai (2019) ‘Political Tensions, Stock Market Dependence and Volatility Spillover: Evidence from the Recent Intra-GCC Crises’, North American Journal of Economics and Finance.

The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect ERF’s stance.