In a nutshell

Efficiency in the management of health resources in MENA countries is imperative and not a matter of choice.

Health efficiency can be reached despite unfavourable economic conditions: a country can be on the efficiency frontier although desirable output targets are not achieved.

The degree of economic development is not a criterion for healthcare system efficiency: in countries with similar economic status, the efficiency of the systems can be widely different.

Improving health and the organisation of healthcare services is becoming increasingly important at local, national and international levels (Deloitte, 2016; OECD, 2014). Improving outcomes of the healthcare system and containing the costs is a particularly significant issue for the MENA region (World Bank, 2013).

To contribute to these regional and global discussions, we examine the efficiency of MENA healthcare systems in terms of their resource use (input approach) and resource exploitation (output approach). Using ‘data envelopment analysis’ (DEA) for a sample of 18 MENA healthcare systems, we shed light on the key determinants of efficiency to inform evidence-based healthcare policy decisions.

With regard to efficiency issues, technical efficiency refers to the relationship between resource inputs and final health outcomes. A healthcare system is considered to be technically efficient when the maximum possible improvement in outcome is obtained from a set of inputs or through the proportional reduction of its inputs while its output proportions are held constant.

Health efficiency in MENA countries

Our empirical results reveal the importance of measuring efficiency in order to achieve the objectives of healthcare policies, such as an optimal selection (input approach) or optimal exploitation (output approach) of the available resources. Therefore, measuring efficiency can be considered as an important tool for assessing healthcare policies and identifying strengths and weaknesses.

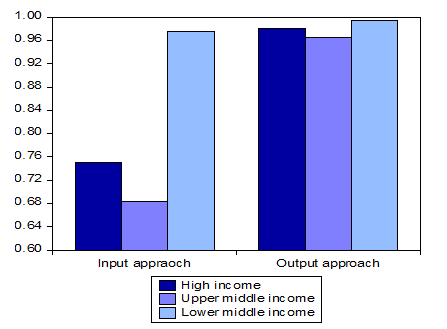

Using the DEA approach, the results show that the input efficiency scores are somewhat different between countries, in contrast with the output efficiency indicators, which appear to be closer.

The DEA results for 2014 indicate that the average efficiency scores for all healthcare systems was 78.7% under the input-oriented approaches, indicating potential savings of 21.3% of total health resources to achieve the current health status of the population if all inefficient countries performed as well as their peers. The generated gains would enhance fiscal space, which could, for example, be reallocated to disease control (Heller, 2005).

The results also show that the health outcome would increase by 2.1% if the funding were appropriately allocated and used. The input efficiency gap between the top 25% healthcare systems and the bottom 25% healthcare systems is substantial (100% versus 56.4% in 2014) while the output efficiency gap is small (100% versus 95.8% in 2014).

The nine efficient countries include all income groups (three high income, two upper-middle-income countries and four lower-middle-income countries). This substantial evidence allows us to consider that achieving optimal levels of efficiency is not associated with belonging to high-income groups (see Figure 1).

The results show that lower-middle-income countries can be a reference for efficiency and best practices in use and exploitation of health resources. Thus, the degree of economic development is not a criterion to measure the efficiency of a healthcare system. It is crucial to note that in countries with similar economic status, the efficiency of healthcare system can be widely different.

Fig. 1 Health efficiency score average by income group (2014)

The analysis suggests that there are considerable efficiency gains yet to be made by some MENA healthcare systems. The DEA results also show that for countries with a low efficiency score and low health outcome, enhancing efficiency is a fundamental issue because large outcome gains can be realised by strengthening the efficiency scheme.

The improvement of efficiency can be achieved by identifying an efficient operating practice, as advocated by Martić et al (2009). The relatively efficient countries have the same rating (100%) although, among them, some are better than others at setting a good example. The findings also show that efficiency is adversely affected by the additive use of resources.

The efficient countries according to the minimisation approach are the same ones according to the maximisation approach, except the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which is an efficient country under the input approach but not under the maximisation approach. This indicates that performance still linked to the success of healthcare policies. The results also show that at any level of health outcome, a country can be technically efficient or inefficient in the use of its health resources.

Analysis of MENA countries’ health production frontier points out that with reference to the input-oriented model, countries on the health production frontier vary slightly from year to year. This illustrates that it is feasible for all countries to reach the efficient frontier through the modification of health resources and providing healthcare services.

This analysis proves that it is not easy for a country to keep its position on the efficiency frontier or to move away from the farthest area. All depend on the health reform progress.

Input and output targets

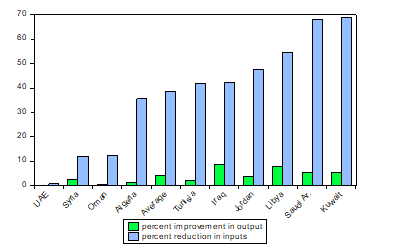

The results for both input and output targets for the two models are shown in Figure 2. Frontier countries are not shown because these countries, by definition, assume the value of 1.

Fig.2 Input and output targets (2014)

In the case of the input model, the input efficiency score is 0.579 for Tunisia. This shows that inputs reduced to 57.9% of their current level while holding life expectancy constant. This would be 42.1% reduction in inputs, while this would be more than 55% in the case of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and, to a lesser extent, Libya. The UAE has to reduce its inputs by only 0.8%.

On average, inefficient countries may reduce their inputs by 38.7%. Retzlaff-Roberts et al (2004) find that the reduction in inputs in OECD countries is 21% on average.

In the case of the output model, the output efficiency score is 0.980 for Tunisia, using a weighted average of Morocco, Lebanon and Bahrain as the frontier composite. This means that Tunisia can potentially increase its life expectancy to 98% without increasing input consumption. This would allow a 2% increase in life expectancy.

The most important and potential improvements concern Iraq and Libya (roughly 8%). For Algeria, Tunisia and Syria, the potential improvement is between 1.3 and 2.7% and only 0.6% for Oman. Retzlaff-Roberts et al (2004) show that the improvement in output is 2.1 years on average for the OECD countries

Determinants of health efficiency

Cross-country analysis of efficiency strongly confirms that healthcare systems have evolved in response to a host of economic, social and institutional backgrounds (Dhaoui, 2019). Indeed, healthcare systems are subject to many issues, especially in relation to financing, inclusiveness, geographical factors or governance.

The results show a negative impact of public health expenditure as a percentage of government expenditure on efficiency. We argue that this relationship should be taken with caution and it would be important to examine it case-by-case.

The results also reveal positive effects of population density, adult literacy, control of corruption and private health expenditure as a percentage of GDP on indicators of efficiency.

Further reading

Deloitte (2016) ‘Global Health Care Outlook: Battling costs while improving care’.

Dhaoui, I (2019) ‘Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in MENA countries: An Analytical and Econometric Approach’.

Heller, P (2005) ‘Who Will Pay? Coping with aging societies, climate change and other long-term fiscal challenges’, IMF.

Martić, MM, MS Novaković and A Baggia (2009) ‘Data Envelopment Analysis: Basic models and their utilization’, Organizacija 42(2): 37-43.

OECD (2014) ‘Geographic Variations in Health Care: What do we know and what can be done to improve health system performance?’, OECD Health Policy Studies.

Retzlaff-Roberts, D, CF Chang and RM Rubin (2004) ‘Technical Efficiency in the Use of Health Care Resources: A comparison of OECD’, Health Policy 69: 55-72.

World Bank (2013) ‘Fairness and Accountability: Engaging in Health Systems in the Middle East and North Africa: World Bank Health Nutrition and Population Sector Strategy for MENA (2013-2018)’.