In a nutshell

Reforms of competition policy are what really matter to ensure a long-run sustainable growth path based on markets with a level playing field at the microeconomic level.

Adoption of competition law is insufficient in itself: what really matters is its implementation – hence, the creation of a competition authority indicates the seriousness of a country about effective implementation of competition policy.

Competition has a positive and statistically significant effect on growth of the trend component of GDP, while its effects on the cyclical component are rather insignificant.

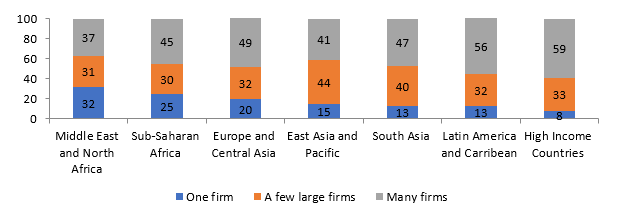

There is a big problem of lack of contestability in markets in the MENA region. As Figure 1 demonstrates, in 2010, the region had the highest share of markets dominated by one firm and the lowest share of markets with many firms.

In the 1990s, many MENA countries relied on structural adjustment programmes. Surprisingly, these programmes implied an orientation towards a market economy structure without an explicit adoption of competition laws.

Competition laws only appeared in the later wave of reforms in the 2000s with the objective of regulating the business environment. Almost all MENA countries have adopted a competition law over the last two decades: the exceptions are Bahrain, Iran, Lebanon, Libya and Palestine.

This raises questions about the extent to which these adjustment programmes help with structural and allocation issues in the beneficiaries’ economies or, instead, focus only on macroeconomic imbalances. We believe that the adoption of competition law is insufficient in itself and what really matters is its implementation. Hence, the creation of a competition authority is one of the indicators that confirm the seriousness of a country about effective implementation of competition policy.

For example, we notice some delays in the creation of a competition authority in comparison with competition law enactment, particularly in the cases of Morocco and Yemen among others. In addition, Djibouti and Iraq enacted a competition law but did not establish a competition authority.

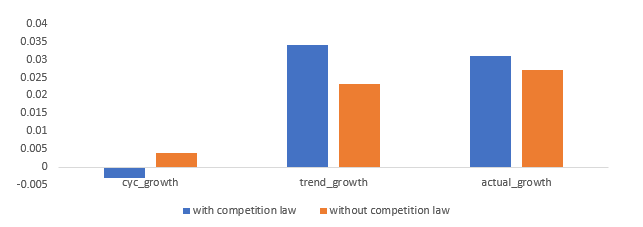

We argue that competition law is an allocation policy that is likely to affect the structure of the economy and hence, its effect will get reflected in the trend component of GDP not its cyclical component. In contrast, other policies, such as fiscal, monetary and tax policies, are more likely to affect the cyclical component of GDP since they are stabilisation policies.

Figure 1: Key market structures by region, 2010 (%)

Source: World Bank (2012)

Figure 2 confirms our assumption: on average over the period from 2007 to 2017, MENA countries with a competition law achieved higher growth of their GDP structural component as well as a higher actual growth compared with those without a competition law.

Figure 2: Cyclical, structural and actual growth in MENA countries (average 2007-2017)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from World Development Indicators, World Bank and MENA countries competition authorities’ websites.

Research assessing the impact of competition policy is scarce in general and, in particular, for the MENA region. We therefore aimed to provide empirical evidence on the impact of competition laws in the MENA region on economic growth in order to stimulate debate on the usefulness of this policy and to provide it with greater legitimacy.

In one study (Youssef and Zaki, 2019a), we first construct our own indices to assess the effectiveness of MENA countries’ competition laws in three categories: enforcement; advocacy; and institutional effectiveness. We extend our assessment of competition rules to all MENA countries in a second study (Youssef and Zaki, 2019b).

Our findings suggest the following: first, the overall assessment of MENA countries’ competition legislation is broadly average. The Maltese and the Algerian legislation are the best performers among the group while the Iraqi and the Yemeni legislation are the weakest. This suggests that there are several potential areas for reform.

Second, most MENA countries revised their laws with some improvements in different aspects. Yet this was not necessarily reflected as an improvement in their overall index. Only the indices for Egypt and Tunisia witnessed the most noticeable improvement in their value following their latest amendment in comparison with earlier drafts.

Third, in terms of the performance of MENA countries’ legislation in the three categories, advocacy seems to be an area of weakness. Moreover, most of these countries’ legislations score better in enforcement against anti-competitive acts compared with institutional effectiveness.

We disentangle the effects of competition laws on growth by distinguishing between the growth of structural and cyclical components of GDP. Our findings show that competition measures exert a positive and statistically significant effect on the growth of the trend component of GDP, while its effects on the cyclical component are rather insignificant.

This result is robust for the two measures of competition we use – the existence of competition law and our own index of overall competition rules – as well as for the three main sub-components of our index: enforcement; advocacy; and institutional effectiveness.

Policy implications

We believe that this discussion of competition policy within the current context of the second wave of reforms in the MENA region is important and timely. After the Arab Spring, several countries in the region once more resorted to international organisations’ reform programmes since their economies were deeply affected by the uprisings.

In particular, the uprisings were a kind of alarm indicating that the region needs to rethink its economic model. For example, even if the MENA countries were to revert back to the pre-uprisings growth levels, this would still be insufficient since it is the quality of growth that matters. But within the context of post-uprisings reform programmes, it seems that structural reforms are still delayed since they are more challenging to implement than stabilisation reforms.

To that effect, structural reforms, including competition policy enforcement, might be sometimes perceived as luxurious reforms compared with pressing social demands and the challenge of macroeconomic imbalances. We argue that these reforms are what really matter to ensure a long-run sustainable growth path based on markets with a level playing field at the microeconomic level.

Further reading

Buccirossi, P, L Ciari, T Duso, G Spagnolo and C Vitale (2013) ‘Competition Policy and Productivity Growth: An Empirical Assessment; Review of Economics and Statistics 95(4): 1324-36.

Carlin, W, S Fries, M Schaffer and P Seabright (2001) ‘Competition and Enterprise Performance in Transition Economies: Evidence from a Cross-country Survey’, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Working Paper No. 63.

Sekkat, K (2009) ‘Does Competition Improve Productivity in Developing Countries?’, Journal of Economic Policy Reform 12(2).

Youssef, J, and C Zaki (2019a) ‘A Decade of Competition Policy in Arab Countries: A De Jure and De Facto Assessment’, ERF Working Paper No. 1301.

Youssef, J, and C Zaki (2019b) ‘Between Stabilization and Allocation in the MENA Region: Are Competition Laws Helping?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1319.