In a nutshell

Small and very small firms in Egypt are more likely to benefit from localisation and diversification compared with large and medium-sized firms.

Service firms benefit more from high levels of diversification, while manufacturing firms gain more from knowledge spillovers and specialisation.

Investing in business cluster development will enhance productivity via economies of agglomeration: for Egypt, one idea would be to develop specialised business clusters based on each governorate’s comparative advantage.

Spatial agglomeration has always been the most important driver of industrial growth in developing countries. The linkage between spatial agglomeration of production and firm productivity has received less attention, particularly in the Egyptian context. Agglomeration brings benefits in two basic ways (Rosenthal and Strange, 2004):

- ‘Localisation economies’, arising from the concentration of firms in the same industry.

- ‘Urbanisation economies’, arising from an increase in city size that enables cross-fertilisation of ideas among diverse economic activities.

Some empirical studies (such as Li et al, 2012) support localisation economies more than urbanisation economies.

There are different arguments about the positive spillover effects of economies of agglomeration. According to the early work of Alfred Marshall, it is better for small and very small firms to cluster together because of the benefits that they obtain from knowledge spillovers, and similarity of cultural and psychological attitudes.

Moreover, agglomeration facilitates the mobility of skilled workers and other specialised inputs for the firms (Krugman, 1991). Finally, the regional system of innovation approach covers broader aspects of innovative relations, including intra-firm as well as extra-firm relations and processes.

On the other hand, agglomeration could be associated with diseconomies of scale. Congestion that occurs from dense firm locations could be severe if infrastructure is a bottleneck to economic activity (Lall et al, 2004).

Among studies that relate several urban agglomeration channels to total factor productivity (TFP), Ellison et al (2010) reveal that all three Marshallian approaches of economies of agglomeration have positive influences, with input-output linkages being extremely important.

This is also supported by the work of Baldwin et al (2010) showing the importance of buyer-supplier networks, labour market matching and local spillovers that enhance productivity within firms. Henderson (2003) finds that local information spillovers have a positive impact on the productivity of high-tech industries but not machinery industries.

Against the background of this body of evidence, we test the association between agglomeration and productivity in the context of Egypt. We combine three different measures of agglomeration:

- Urbanisation or firm diversification, measured by the number of firms in a governorate.

- Localisation and specialisation, measured by the average productivity in the governorate and sector.

- Competition, measured by the number of firms in the same sector operating in the governorate.

We take account of heterogeneity implied by economic activities, firm size and firm location. We analyse a rich dataset of firms in 342 four-digit activities in 27 governorates, adding up to a total of 62,108 firms, to examine the effect of agglomeration on firm productivity.

The Egyptian case is particularly interesting since the industrial sector has been facing several problems affecting its productivity, and the government is currently implementing several structural reforms to improve its competitiveness. Hence, an evidence-based study on the importance of clusters and agglomeration is crucial from a policy perspective.

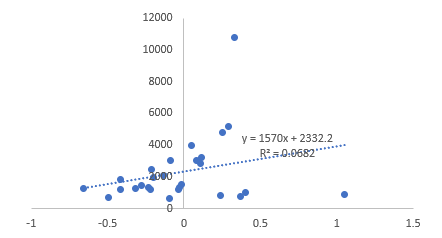

Overall, we find strong evidence for the existence of agglomeration economies in Egypt after controlling for firm age, location, economic activity and legal status (see Figure 1). Similar to other work on Egypt (Howard et al, 2014), we find that productivity spillovers gained from agglomeration economies outweigh the negative effects of congestion due to competition. The latter is probably due to the lack of adequate infrastructure.

Breaking the analysis down by firm size and activity, our findings show first that small and very small (‘micro’) firms are more likely to benefit from localization and diversification compared with large and medium-sized firms. We also find that service firms benefit more from high levels of diversification, while manufacturing firms gain more from knowledge spillovers and specialization.

Figure 1:

Correlation between TFP and cluster size

Source: Constructed by the authors using the Economic Census data.

Note: The cluster size is measured by the number of firms by governorate.

Our study highlights the importance of investing in business cluster development to enhance productivity through economies of agglomeration. One policy recommendation would be to develop specialised business clusters based on each governorate’s comparative advantage.

Furthermore, these clusters should have the appropriate hybrids of different firm sizes. As highlighted in this research, smaller firms tend to have higher TFP, and micro, small and medium-sized firms all benefit from specialisation and diversification spillovers resulting from agglomeration.

Policy implications

From a policy perspective, first, facilitating mobility of factors of production (labour and capital) is integral to promote economies of agglomeration and thereby boost firm productivity. Enhanced transport and access to markets close to business clusters locations is one policy option the government.

Second, further development of existing business clusters is needed. Government efforts should be focused on supporting existing business clusters, expanding the supply chain, and linking them to markets (internal and external). Rigorous efforts are needed to enhance existing clusters, to develop further the supply chain of feeding industries, and to foster specialisation. We recommend establishing specialised industrial zones for promising business clusters with high growth potential.

Third, the government should invest in human capital by providing vocational education and training centres that are related to the business clusters. These human capital centres would be in the proximity of the business clusters. A tripartite arrangement among the ministry of trade and industry, the ministry of higher education and the private sector could be useful in setting vocational education and training programmes for labour working in these industries.

Fourth, enhancing access to finance for firms in these business clusters is important to ensure sustainability and growth. Access to finance is one of the obstacles facing firms in Egypt in general. The government and the banking sector should enhance access to finance for firms in these clusters and develop customised financial product that could help in financing their working capital needs and increasing investments.

Fifth, in terms of infrastructure, the government should ensure that proper infrastructure is well connected to business clusters all over Egypt. Electricity, water, sanitation and waste disposal systems are important factors to attract business and develop clusters.

Finally, on the sectoral side, manufacturing will benefit most from specialisation. Hence, promoting business clusters in manufacturing and creating a value chain could greatly enhance the productivity of the sector and promote forward and backward linkages. On the other hand, services will benefit most from spillovers resulting from diversification.

This work has been financed by an ERF research grant.

Further reading

Baldwin, John, Mark Brown and David Rigby (2010) ‘Agglomeration Economies: Microdata Panel Estimates from Canadian Manufacturing’, Journal of Regional Science 50(5): 915-34.

Ellison, Glenn, Edward Glaeser and William Kerr (2010) ‘What Causes Industry Agglomeration? Evidence from Coagglomeration Patterns’, American Economic Review 100(3): 1195-1213.

Henderson, Vernon (2003) ‘Marshall’s Scale Economies’, Journal of Urban Economics 53(1): 1-28,

Howard, Emma, Carol Newman, John Rand and Finn Tarp (2014) ‘Productivity-enhancing Manufacturing Clusters’, UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 71.

Krugman, Paul (1991) ‘Increasing Returns and Economic Geography’, Journal of Political Economy (99(3), 483-99.

Lall, Somik, Zmarak Shalizi and Uwe Deichmann (2004) ‘Agglomeration Economies and Productivity in Indian Industry’, Journal of Development Economics 73: 643-73.

Li, Dongya, Yi Lu and Mingqin Wu (2012) ‘Industrial Agglomeration and Firm Size: Evidence from China’, Regional Science and Urban Economics 42: 135-43.

Rosenthal, Stuart, and William Strange (2004) ‘Evidence on the Nature and Source of Agglomeration Economies’, in Handbook of Urban and Regional Economies edited by Vernon Henderson and Jacques Thisse, Elsevier-North Holland.