In a nutshell

The critical juncture in the history of global oil prices was 1949-50 when the point of equalisation shifted from North Europe to the East Coast of the United States.

Given the potential oil reserves in the Persian Gulf, 1950 constituted the breakthrough moment when the Middle East became the central axis of the world petroleum economy.

With the official price at $1.75 per barrel, Middle East producers could beat the competition everywhere.

How did the Middle East become both a new geographical base-point for petroleum transactions and the hub of the global pricing system?

Several giant Middle East oilfields were discovered between 1943 and 1947. Before that, the United States and the Gulf of Mexico region produced the bulk of the oil consumed in the world. Maintaining a global price equilibrium was essential for the US economy, as well as the country’s international power and engagement in war efforts. The disclosure of the region’s potentially large reserves – and low production costs – rendered the global pricing equilibrium more difficult to sustain.

To deal with the price dilemmas they were facing, corporations and governments came up with a pricing method called netback. The idea was to make Middle East oil reach Western markets at the same price as oil produced in the Americas.

Our research shows that the netback pricing method provided the solution for many of these dilemmas. In effect, this estimation method was flexible enough not only to serve as a reference for normative regulatory policies but also as an instrument for different business strategies.

Below we try to convey how two interpretations of the netback pricing formula emerged in the Middle East, endorsed respectively by the Exxon and Gulf Oil companies.

In June 1948, Eugene Holman, then president of the giant New Jersey-based Exxon oil corporation, announced to the press his commitment towards netback prices for Saudi Arabian Light crude, with Caribbean oil as the key reference point (basing point).

To arrive at the netback price, they summed up the price of an equivalent Venezuelan oil (Jusepin crude) with the travel costs to the final destination (in this case from Maracaibo to Southampton), and then subtracted the transport costs from Saudi Arabia to Southampton.

The resulting number was what crude oil should be priced free on board (FOB) at the Saudi Arabian port of Ras Tanura. When it arrived in Southampton it would have the same customs, insurance and freight (CIF) price of Venezuelan crude. That was the Arabian crude netback price prevailing in the British Isles.

With this system, British consumers paid the same price for oil from different geographical sources. Some weeks earlier, the netback pricing methodology had also been suggested by the Marshall Plan’s agency to streamline Middle East oil procurement and supply this essential commodity for the reconstruction of Europe.

Incumbent market leaders, such as Exxon (or Royal Dutch Shell), which had a strong presence not only in the United States but also in other producing regions, including Indonesia, Romania, Austria, Venezuela, Peru, Colombia, Canada and the Middle East (not to mention their former stakes in the Soviet Union and Mexico wiped out by nationalisations), stood to gain considerably from this international pricing system.

Such prices would return extra profits for their low-cost Middle East oil production fields, while defending investments already made in exporting countries with mature oilfields. If they had used competitive cost-plus prices, they would have pushed Arabian oil into competing with their Venezuelan and Texan subsidiaries in Western hemisphere markets, hurting the businesses of core companies while enabling fast growth in the Middle East’s market share.

Holman’s commitment to netback pricing underpinned Exxon’s engagement with global prices. He wanted to escape the crossfire unleashed in the Senate and in Congress against the practices of big oil corporations. The time was ripe for a public rejoinder. In the ensuing months, the Marshall Plan’s authorities concurred with the position that Exxon’s netback pricing formula ‘qualified as a competitive price’ for allocation purposes. The pricing dilemma had therefore been satisfactorily solved.

However, the entire architecture would soon be shattered through its own backdoor, due to the onset of US petroleum imports. When the Persian Gulf surplus became large enough to flow into North America, a second equalisation point surfaced.

As of 1949, all companies stuck to the official Marshall Plan-financed prices of $2.03, $1.97 and $2.76 per barrel for Arabian, Kuwait and Iraq crudes, respectively, then getting exported to Europe. However, they used a different price list for oil heading to the US East Coast, charging $1.43, $1.30 and $1.75 per barrel, respectively, for similar shipments, accounted for as intra-company transactions.

As long as these transactions were not subject to arm’s length bargaining, they could remain undisclosed and under the seal of commercial secrecy. However, keeping such a conspicuous trade flow concealed for a long time proved difficult.

The discovery of shadow prices in crude transactions sent shock waves throughout America. Netback prices now appeared merely as a cover for overcharging the European aid programme while the companies pursued a policy of competitive transfer pricing in corporate business dealings with the United States.

Homeland discontent mounted in many quarters, spearheaded by organisations representing the independent oil companies that accused the assistance programme of using American taxpayer money to subsidise a few private concerns in permitting them to dump surplus oil in American markets.

All such endeavours resulted in greater pressure on the oil majors to close the gap between the intra-company transfer prices and the official financed prices. In February 1949, Paul Hoffman, the Marshall Plan director, informed the companies that the price charged for Middle East crude oil sales to the United Sates had an important bearing on determining the competitive market price, and furthermore requested a global re-examination of this issue.

The reactions were contradictory, with New Jersey Standard-Exxon, Standard of California-Chevron and Texaco blatantly refusing any reduction in the netback price of $2.03 per barrel, while Socony-Mobil agreed to think the issue over.

Retreating from parallel pricing, Gulf Oil then broke with the oligopolistic consent and yielded two price reductions: the first was 15 cents in April 1949; the second was 13 cents in July 1949. With the downward adjustment in official Kuwait crude 31º API oil prices to $1.75 per barrel, all the majors were compelled to follow suit, pushing the marker for Saudi light crude to $1.71 per barrel.

Gulf Oil’s historical deviation in pricing best illustrates the prevalence of corporate self-interests over collusive practices. It stood out as the most deviant firm, at least in potential terms.

In contrast with the other oil multinationals, the company explored the fastest growing oilfields in the Middle East, supplied residual demand for crude and petroleum products in Europe (that is, the available portion of market demand not supplied by other firms already in the market), and met core demand for crude in the United States where it operated a highly integrated business based on its East Texas oilfields.

For these reasons, Gulf Oil would only ever be marginally affected by any possible change in the Marshall Plan pricing policy while still enjoying the freedom to replace European sales with American ones.

Ironically, all the efforts to objectify the pricing policy by grounding decisions on formulas ended up in prices being set by successive calibrations and negotiations. From the viewpoint of the authorities, while the $2.03/barrel ceiling rested on a system of logic (the main trade flows to Europe) and a principle of equity (netback equalisation), the $1.75/barrel Gulf Oil price was simply a ‘token reduction’ imposed by the circumstances.

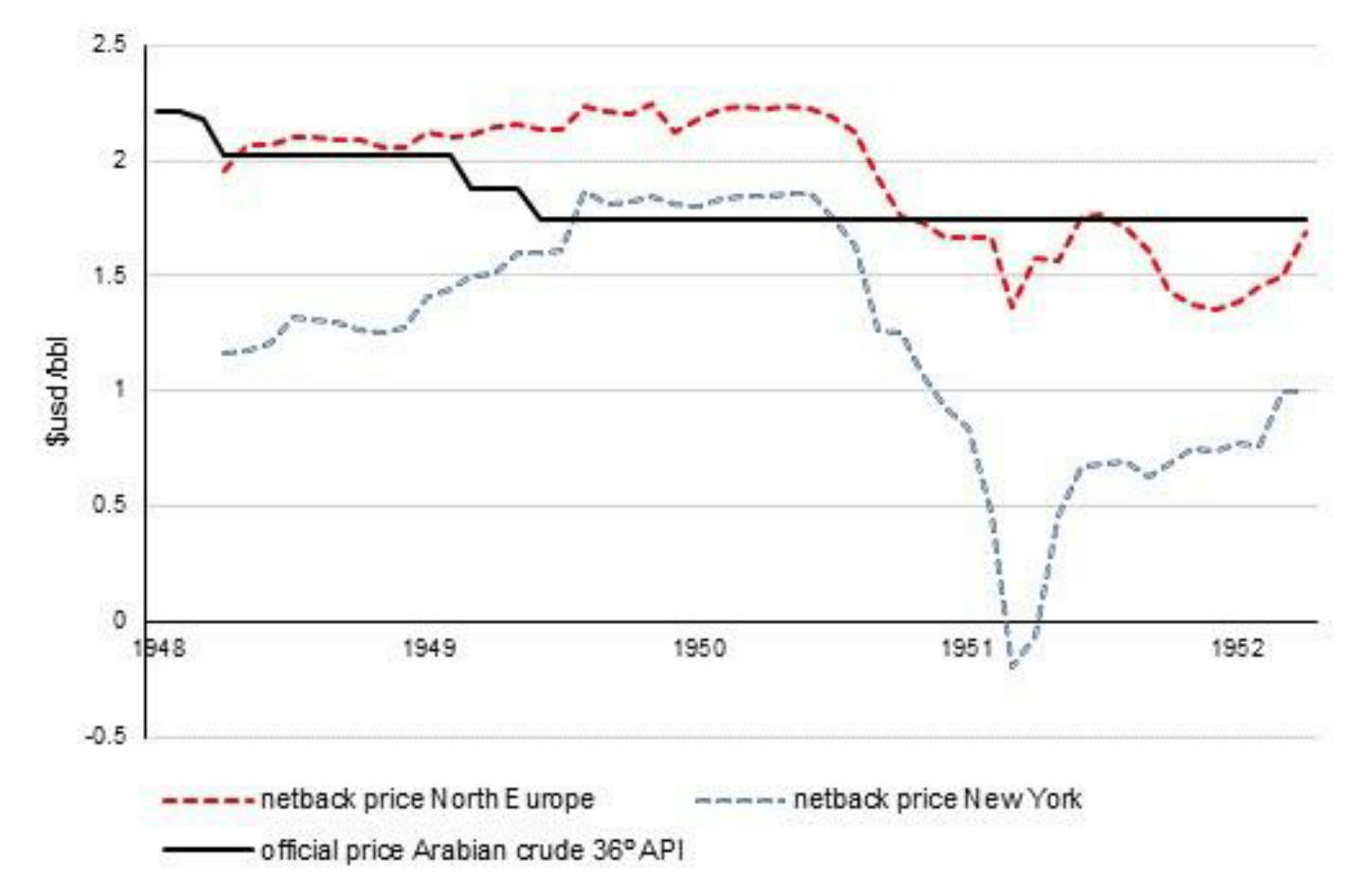

To ascertain whether this new Middle East oil price was a just and arbitrary calibration, we have reconstructed the time series for official Saudi Arabian crude prices and the corresponding netback price with Southampton-England and New York-USA as equalisation points. The result shows that the Gulf Oil ‘token reductions’ in fact almost perfectly matched North America netbacks throughout 1950 (see Figure 1).

The critical juncture of 1949-50 became a turning point in the history of global oil prices because it shifted the point of equalisation from North Europe to the East Coast of the United States. Indeed, given the potential oil reserves in the Persian Gulf, 1950 constituted the breakthrough moment when the Middle East became the central axis of the world petroleum economy.

With the official price at $1.75 per barrel, Middle East producers could beat – or at least equal – the competition everywhere. When prices were aligned by the US netback, a new yardstick ultimately emerged. Moreover, with exports to the US, the tendency for only one FOB price level to be effective for all destinations inevitably followed suit.

A global oil pricing system briefly emerged out of this chain of events, interlinking Middle East production centres in the Eastern hemisphere with the American and Caribbean oilfields in the Western hemisphere. Under stable freight tanker rates, this system ensured the global competitiveness of the Persian Gulf petroleum region.

This column, which was originally published on LSE Business Review, is based on Squabbling Sisters: Multinational Companies and Middle East Oil Prices by Nuno Luís Madureira, Business History Review, 2017 (91) 4: 681-706.

Figure 1:

Time series for official Saudi Arabian crude prices and the corresponding netback price with Southampton and New York as equalisation points

Sources and methods: Madureira, 2017