In a nutshell

Achieving structural transformation in MENA countries requires easing the movement of capital and workers from traditionally strong sectors, such as construction and public services, to higher value-added industries.

In particular, labour and business regulations should not hamper the ability to close down inefficient businesses and start new ones.

Higher infrastructure investment could also stimulate workers to move to higher-productivity industries as wages in these sectors increase.

The nature of economic growth is as important as its level in improving the median household’s standard of living and lifting a country out of the middle-income trap. This kind of transition towards a modern economy – in which advanced sectors start employing the lion’s share of the labour force and acting as drivers of overall productivity – has been labelled ‘structural change’.

Its role in the development of South-East Asian countries has been recognised as a major driver of their success in improving labour productivity and lifting people out of poverty. In contrast, countries in the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean region have remained stuck in the middle-income trap, even as overall economic performance improved.

The relatively low improvement in labour productivity in Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia during their high-growth decade in the 2000s remains a puzzle. It could explain the stagnation felt by many in those countries, which eventually led to the Arab Spring.

This paradox – in which economic growth is associated with political and social unrest – needs to be understood to redress the deep frustrations currently expressed by a significant segment of the population of the Middle East.

Growing without changing

A key insight from our research into the process of ‘growth without change’ comes from decomposing the sources of growth. It is important to distinguish structural change from growth arising from better technologies and production processes within each sector, which can lead to higher returns to capital. The former is the phenomenon whereby labour moves from low-productivity sectors (such as agriculture or personal services) to more advanced industries, including manufacturing and services.

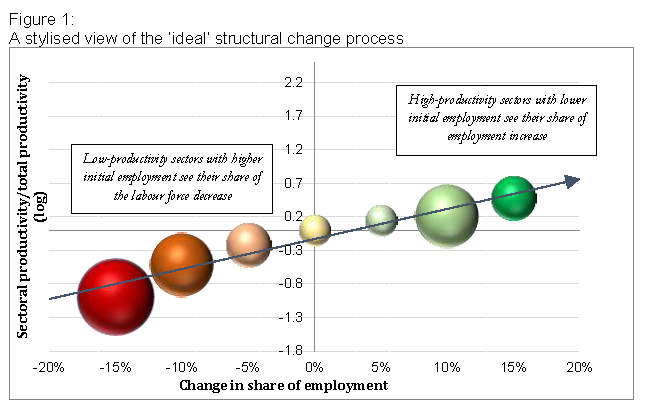

When structural change happens, even if productivity within each sector remains constant, average productivity in the economy improves since the labour force is used in more efficient sectors. This requires movements of labour to be positively correlated with relative productivity in each sector so that the most productive industries gain a bigger employment share at the expense of less productive activities.

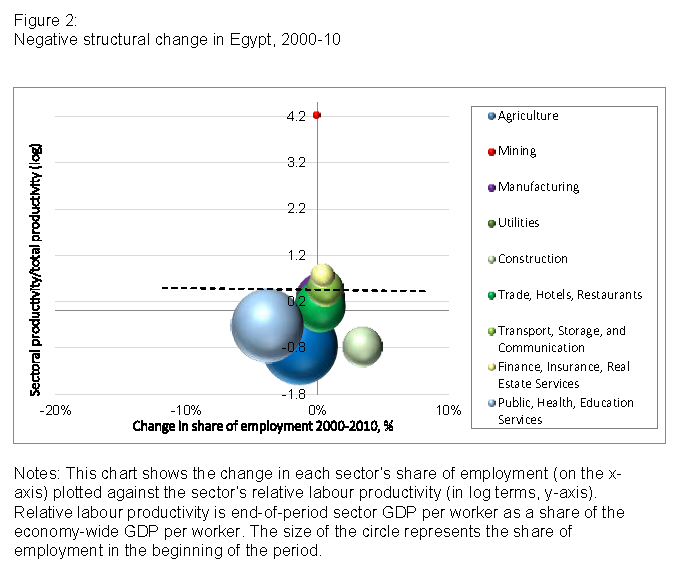

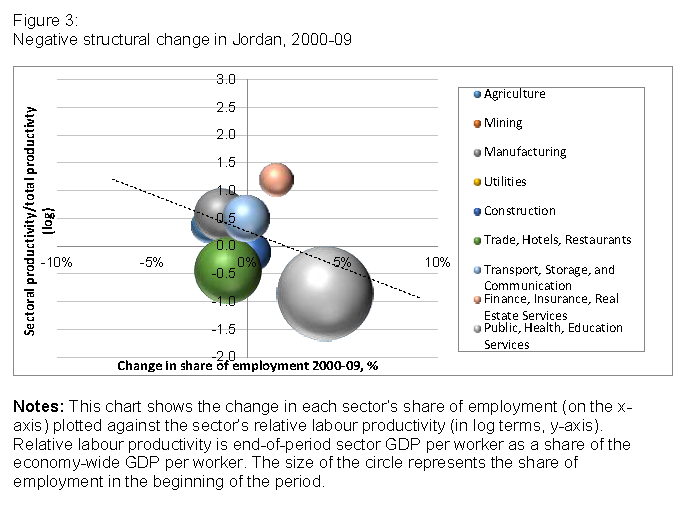

The ‘ideal’ process of structural change is illustrated in Figure 1 below. But as Figures 2 and 3 show, the exact opposite happened in Egypt and Jordan, with labour flowing from productive sectors to less efficient ones, notably public and social services.

Comparing the experience of MENA countries with other emerging economies, a key finding of our research is that the former did not undergo structural change, even during the decade of relatively good economic performance of the 2000s.

We decompose the roughly 20% growth in output per person employed in Egypt over the period from 2000 to 2010 into positive growth within sectors (keeping labour shares across sectors constant), and growth due to a shift of labour across sectors. A lack of structural change actually slowed down productivity growth by a cumulative -7.5% over the decade, as labour flowed from high-productivity sectors, such as mining, to lower value-added sectors, notably construction and public services.

In the same way, negative structural change in Jordan reduced the pace of productivity growth by a cumulative 2% over the decade, as labour flowed into the low-productivity public and social services sector, and the share of the highly-productive manufacturing sector in employment actually decreased.

What drives structural change?

A key question remains: what drives structural transformation? Analysing a database covering 27 countries over two decades, we examine labour reallocation across nine sectors of the economy and the extent to which it was linked to relative labour productivity.

We show that countries that experienced increased openness to trade were more likely to undergo structural transformation, as inefficiencies were corrected by foreign competition and advanced sectors benefitted from integration into global value chains. Similarly, higher credit to the private sector was likely to foster the development of more advanced sectors and the reallocation of labour towards these industries.

Countries that had a large initial untapped labour force in agriculture also experienced higher levels of structural change by transferring this rural population towards urban, industrial sectors. A 1% higher initial share of employment in agriculture was associated with a 0.4% increase in cumulative productivity growth related to structural change.

In contrast, initial specialisation in raw material exports led to a ‘Dutch disease’ phenomenon, slowing down structural change. A 1% higher share of primary commodities in exports led to a 0.2% decrease in cumulative structural change.

This analysis suggests that MENA countries did have the means and conditions to ignite structural change on a similar scale to that seen in, say, Thailand or Turkey. Their opening to trade in the 2000s and the relatively large initial share of employment in low-productivity sectors offered key enabling initial conditions for structural change.

But their inability to do so, particularly in Egypt and Jordan, relates to inefficiencies in the allocation of resources in the economy, and it is closely related to their population’s frustration with the economy as it currently operates.

Lessons learned

The failure to ignite structural change lies in deeper impediments, peculiar to these countries’ business climate, regulations, and economic and social organisation. Such hindrances to the efficient reallocation of the labour force can arise both within sectors, and from a more macroeconomic perspective. They suggest the need for policy reforms to remove constraints on the modernisation of MENA economies.

Achieving structural transformation in these countries requires easing the movement of capital and workers from traditionally strong sectors that provide too few ‘jobs’ – such as construction and public services – to higher value-added industries. In particular, labour and business regulations should not hamper the ability to close down inefficient businesses and start new ones.

Higher infrastructure investment could also stimulate workers to move to higher-productivity industries as wages in these sectors increase. The focus of public spending on current expenditures rather than infrastructure investment could have hindered geographical mobility and the movement of workers towards clusters of high value-added industries.

In Egypt and Jordan, in particular, the low and declining share of public investment (respectively 22% and 23% of total investment in 2010) can partly explain the lack of basic infrastructure that can support labour mobility out of rural areas and into clusters of high-productivity economic activities.

Last but not least, it will be important to continue removing the artificial support for low value-added industries (such as construction, agriculture and public services) provided through longstanding subsidies, and rising public sector employment.

Ultimately, a level-playing field across sectors must be established to enable a rapid and more efficient reallocation of labour towards the most productive industries in the region, and to provide well-paid jobs to an ever-growing working age population.

Further reading

Morsy, Hanan, Antoine Levy and Clara Sanchez (2015) ‘Growing without Changing: A Tale of Egypt’s Weak Productivity Growth’, ERF Working Paper No. 940.