In a nutshell

For MENA countries, international financial integration has both positive and negative effects, with potential risks that may outweigh the benefits if not managed properly.

Regional financial integration offers a more promising path for fostering financial development and governance; by focusing on regional ties and adopting cautious policies on international financial integration, MENA economies can chart a path to sustained growth and stability.

Good governance is key to maximising the benefits of financial integration: MENA countries should focus on improving the rule of law, reducing corruption and enhancing political stability to create a favourable environment for both international and regional financial flows.

Conventional economic theory suggests that international movement of capital provides many benefits including better risk-sharing, more efficient capital allocation and higher growth. The crisis in many emerging market and developing economies during the 1990s and early 2000s have led to reassessment of the theoretical benefits of financial openness.

A more recent report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts a slowdown in the growth prospects for both advanced economies and emerging market and developing economies (World Economic Outlook, 2023). Under the pro-cyclicality of capital flows suggested by Kaminsky et al (2004), this projection may imply slowdowns in both financial flows and international financial integration.

These outcomes may prevent countries from reaping the beneficial effects of international financial integration. In this context, regional financial integration has emerged as a complementary subset to international financial integration.

Frey and Volz (2013) define regional financial integration as ‘the process of opening up capital accounts among countries of geographical proximity, including a liberalisation of cross border activities of financial institutions within the integrating area’. Research on this topic, which includes Garcia-Herrero and Wooldridge (2007), Park and Lee (2011) and Eyraud et al (2017), suggests that regional financial integration promotes good practices in financial systems and diminishes their sensitivity to external shocks and asymmetric information.

In a new study, we consider gross stocks of bilateral financial flows data prepared by Pagano et al (2020) to construct a quantity-based measure of regional financial integration in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) economies (Özmen and Taşdemir, 2024). In a similar vein to international financial integration, we define regional financial integration as the sum of gross stocks of financial assets and liabilities (as a percentage of GDP) between the MENA economies.

International financial integration

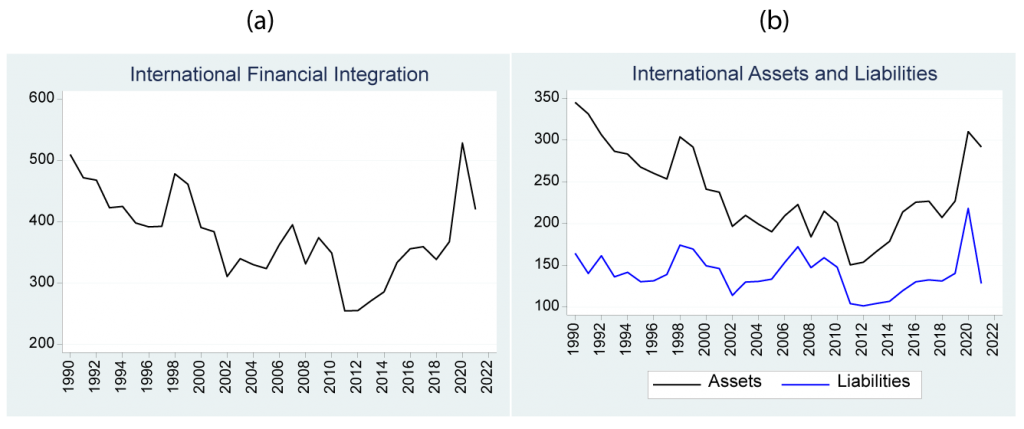

Figure 1.a shows the evolution of mean international financial integration (the sum of gross stocks of assets and liabilities, as a percentage of GDP) during the period from 1990 to 2021. Accordingly, international financial integration tends to diminish during the first two decades and then it increases during the rest of the period.

In Figure 1.b, international financial integration is broken down into asset and liability flows. Throughout the period, asset flows consistently exceeded liabilities . This indicates that MENA countries are net exporters of capital, possibly reflecting a flight to safety by local investors.

Figure 1: International financial integration in MENA

Regional financial integration: a complementary approach

Figure 2 shows the network diagram of financial flows within MENA. The direction and thickness of arrows denote, respectively, the movement of capital from the reporter to destination country and the size of financial flows between the reporter and destination country.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) appear to have more financial asset transactions with each other than non-GCC MENA economies. Bilateral flows between Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey stand out, indicating their roles as regional financial hubs.

Figure 2: Regional financial asset transactions in MENA

Financial development: the effects of international and regional financial integration

A remarkable study by Kose et al (2009) suggests that the beneficial effects of financial integration often operate through indirect channels, such as financial development and governance, ultimately resulting in total factor productivity growth and macroeconomic stability.

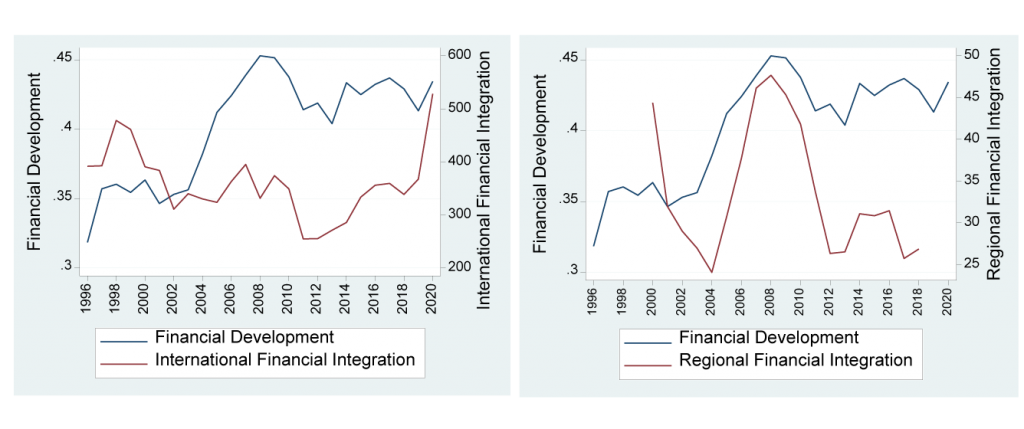

Figure 3 shows the evolution of international and regional financial integration along with financial development. It seems that financial development tends to move together not only with international financial integration but also with regional financial integration. But our empirical findings suggest that while ‘too much’ international financial integration mitigates domestic financial development, high levels of regional financial integration promote it.

Figure 3: Financial development and international and regional financial integration in MENA

Governance: the effects of international and regional financial integration

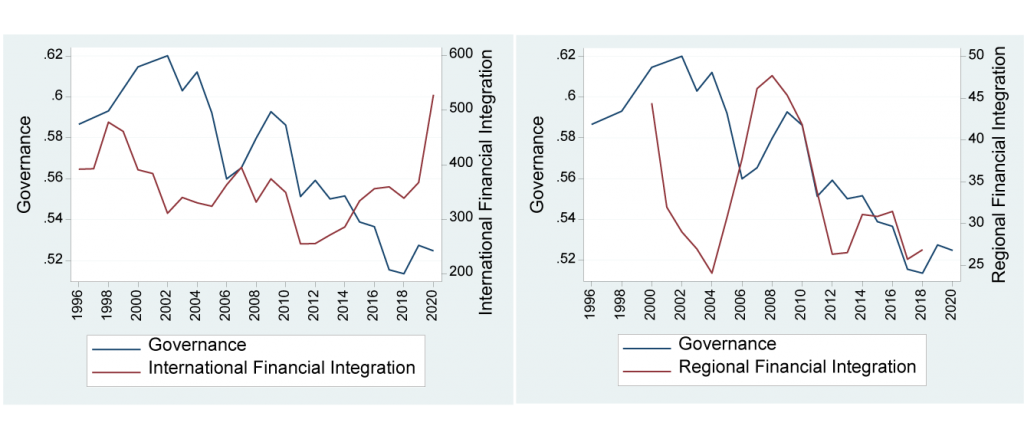

Figure 4 highlights the relationship between governance and both international and regional financial integration in MENA. While governance initially improves with international financial integration, the trend reverses after 2015, raising concerns about the long-term impact of international financial integration on institutional stability.

In contrast, regional financial integration is positively associated with governance, as regional financial ties promote better institutional development. This is particularly important in a region where governance indicators – such as the rule of law, political stability and control of corruption – remain relatively weak.

Our empirical findings suggest that high levels of both international and regional financial integration lead to a better institutional environment by reducing corruption, the increasing rule of law, and promoting government effectiveness and political stability.

Figure 4: Governance and international and regional financial integration in MENA

Conclusion

The debate over financial integration in MENA is far from settled. International financial integration has both positive and negative effects, with potential risks that may outweigh the benefits if not managed properly.

In contrast, regional financial integration offers a more stable and promising path for fostering financial development and governance. By focusing on regional ties and adopting cautious policies towards international financial integration, MENA economies can chart a path to sustained growth and stability.

Policy recommendations

MENA countries should place greater emphasis on regional financial integration, which fosters financial stability and development. By strengthening regional ties, countries can insulate themselves from global financial shocks while building more resilient financial markets.

While international financial integration can bring benefits, MENA economies should focus on macroprudential regulations to mitigate the risks of capital flight and to ensure that domestic financial systems may absorb foreign capital inflows without destabilising effects.

Good governance is a key pillar for maximising the benefits of financial integration. MENA countries should focus on improving rule of law, reducing corruption, and enhancing political stability to create a favourable environment for both international and regional financial flows.

Developing stock and bond markets will be essential for efficiently allocating capital and reducing the reliance on banks, which are often state-owned and inefficient. Encouraging private sector participation and foreign direct investment can help deepen financial markets.

Although GCC countries dominate regional financial flows, broader inclusion of non-GCC MENA economies could lead to stronger regional integration. Expanding regional financial integration across the region will promote shared interests, economic growth and political stability.

Further reading

Eyraud, L, D Singh and BW Sutton (2017) ‘Benefits of global and regional financial integration in Latin America’, IMF Working Paper No. 2017/001.

Frey, L, and U Volz, U (2013) ‘Regional financial integration in Sub‐Saharan Africa – An empirical examination of its effects on financial market development’, South African Journal of Economics 81(1): 79-117.

García-Herrero, A, and P Wooldridge (2007) ‘Global and regional financial integration: Progress in emerging markets’, BIS Quarterly Review 57.

International Monetary Fund (2023) World Economic Outlook 2023.

Kaminsky, GL, CM Reinhart and CA Végh (2004) ‘When it rains, it pours: Procyclical capital flows and macroeconomic policies’, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 19: 11-53.

Kose, MA, E Prasad, K Rogoff and SJ Wei (2009) ‘Financial globalization: A reappraisal’ IMF Staff Papers 56(1): 8-62.

Özmen, E, and F Taşdemir (2024) ‘Structural Domestic Conditions, Regional and International Financial Integrations: Evidence from MENA’, ERF Working Paper No. 1728.

Pagano, A, M Nardo, N Ndacyayisenga and S Zeugner (2020) ‘FINFLOWS: A database for bilateral financial investment stocks and flows’, European Commission, Joint Research Centre.

Park, CY, and JW Lee (2011) ‘Financial integration in emerging Asia: Challenges and prospects’, Asian Economic Policy Review 6(2): 176-98.