In a nutshell

The insights of 14th century historian Ibn Khaldun remind us that when wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few through unfair means, the resulting instability can weaken the very foundations of a nation.

The evidence of extreme inequality in Arab countries, particularly Lebanon, underscores the need for policies that do more than just reduce poverty: they must also address the unchecked power and influence of the wealthiest to foster a more equitable and stable society.

Policy-makers must urgently address the extractive governance structures that enable a few to prosper while the majority struggle; without reforms that tackle both ends of the spectrum, poverty and plutonomy, social unrest and further instability are likely to deepen.

Inequality in the Arab world is not just a question of poverty or extreme affluence: it’s about both. In the field of applied welfare economics, two subfields traditionally operate in isolation, each offering crucial insights but only into part of the problem.

Poverty analysis focuses on the lower end of the income distribution, highlighting the need to address the most severe forms of deprivation and exclusion. From a social injustice standpoint, this approach is essential because it points to systemic barriers that trap the poorest in cycles of disadvantage, making targeted interventions critical for restoring fairness and dignity.

At the other extreme, plutonomy analysis (a term introduced by Makdissi and Yazbeck, 2015), focuses on the top of the distribution from a measurement perspective. It examines how wealth concentration among a small elite affects the overall distribution of resources.

This builds on the seminal work of Piketty (2003), which emphasises the importance of studying income and wealth concentration at the top. The outsized influence that these elites wield, not just in markets but also in politics and social norms, makes the top of the distribution crucial for understanding the broader implications of inequality.

Although these individuals’ names are available, this is irrelevant from an economist’s perspective. From an epistemological standpoint, I treat this information as anonymous, looking at a distribution with an anonymity perspective as if I was standing behind what John Rawls called the veil of ignorance.

If a system allows an individual to achieve such wealth and this person has the opportunity to do it, why should they refrain from doing it? If the institutions of a country permit such wealth accumulation, the focus should be on reforming those institutions, especially if the resulting socio-economic system is considered socially unjust.

What happens when we combine these two perspectives? Here, I take what I call a censored bipolarisation approach, comparing Arab countries through both the poverty and plutonomy lenses. By doing so, we capture the extreme polarisation between the poor, who suffer from exclusion and deprivation, and the ultra-wealthy, who wield immense power over economic and political systems. This stark polarisation undermines social cohesion and threatens stability by creating fertile ground for social unrest and resentment.

In his Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun warned that the unjust extraction of wealth by ruling elites and oppressive taxation could erode the economic base of society, leading to its eventual decline. His insights remind us that when wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few through unfair means, the resulting instability can weaken the very foundations of a nation.

The data challenge in the Arab world

One of the main difficulties in building a regional picture of inequality, poverty and wellbeing in the Arab world is the critical issue of data deprivation. As Atamanov et al (2020) points out, the availability of household data in the region is significantly below expectations, given the levels of development.

To address this gap, I turn to alternative sources of information, following Makdissi et al (2024). I combine data on income sufficiency from the Arab Barometer with information on fortunes from the Forbes Billionaires List.

Mapping poverty and plutonomy

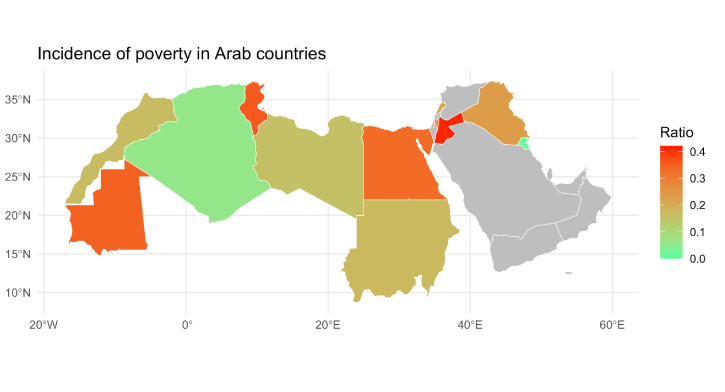

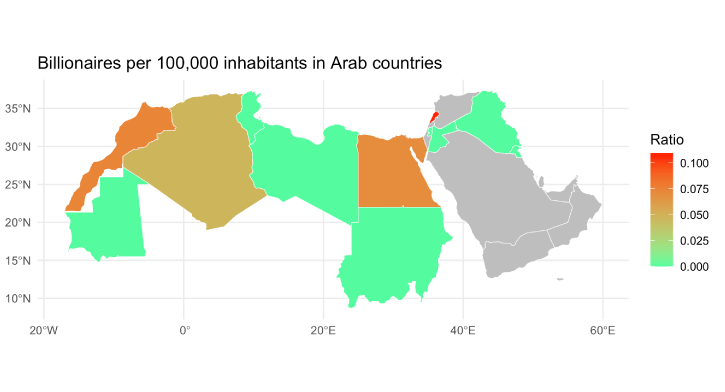

Figures 1 and 2 present maps of the region. Figure 1 displays the incidence of poverty, while Figure 2 shows the number of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants. Although these figures are informative in isolation, combining these perspectives offers a more complete picture of extreme inequality in the region.

Introducing the extreme bipolarisation index

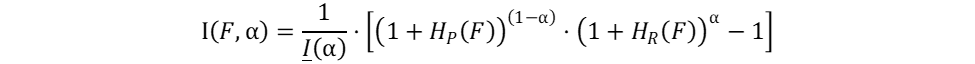

To capture the dynamics of both ends of the income spectrum, I propose an extreme bipolarisation index, defined as:

where F represents the cumulative distribution of income, Hp(F) the usual poverty headcount, and HR(F), the number of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants.

I introduce an index ![]() representing aversion to plutonomy. When

representing aversion to plutonomy. When ![]() there is no aversion to plutonomy and the index is equal to the incidence of poverty. When

there is no aversion to plutonomy and the index is equal to the incidence of poverty. When ![]() , there is no aversion to poverty and the index is equal to the ratio of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants. In this context, when we are between 0 and 1, an increase in

, there is no aversion to poverty and the index is equal to the ratio of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants. In this context, when we are between 0 and 1, an increase in ![]() represents an increase in aversion to plutonomy.

represents an increase in aversion to plutonomy.

Finally, ![]() is a normalisation parameter that ensures that the index takes values between 0 and 1. We picked the ratio of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants to make sure no country on the planet actually has a ratio exceeding 1. If we had chosen the ratio per 10,000, some extreme cases, not from the Arab world, would have a ratio higher than 1.

is a normalisation parameter that ensures that the index takes values between 0 and 1. We picked the ratio of billionaires per 100,000 inhabitants to make sure no country on the planet actually has a ratio exceeding 1. If we had chosen the ratio per 10,000, some extreme cases, not from the Arab world, would have a ratio higher than 1.

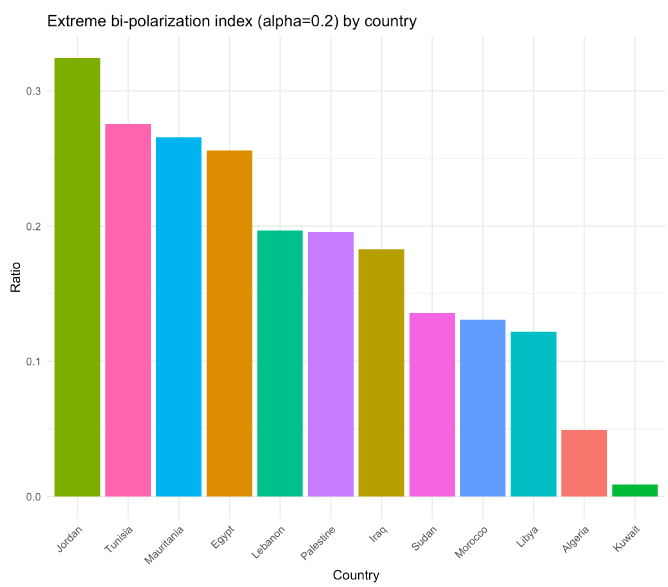

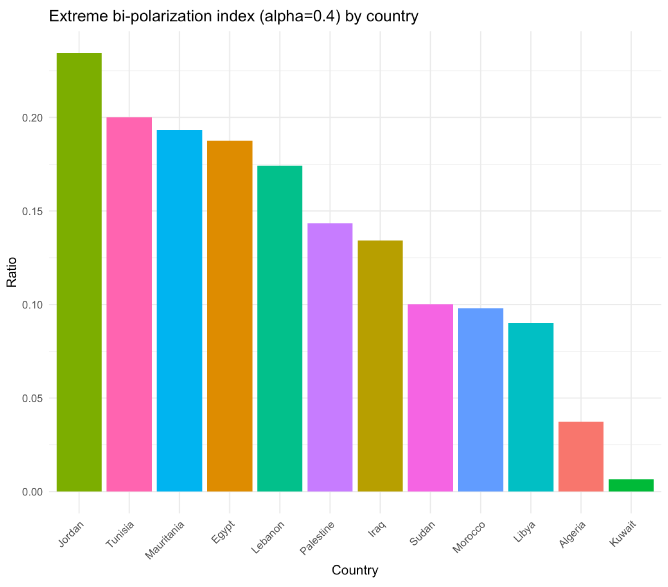

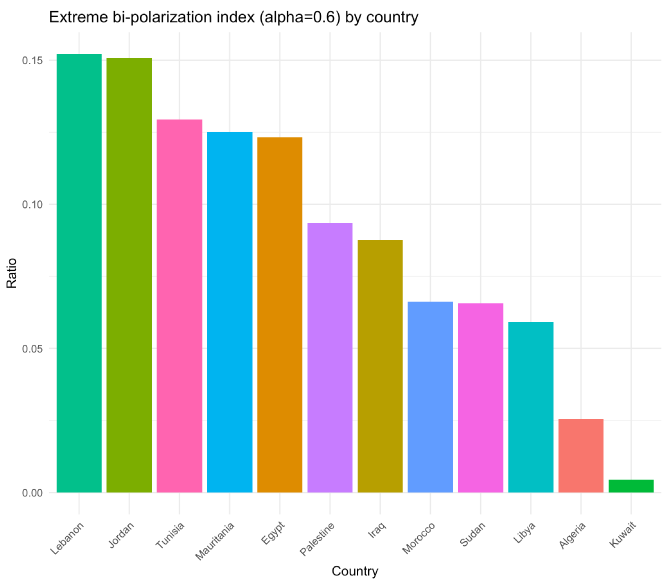

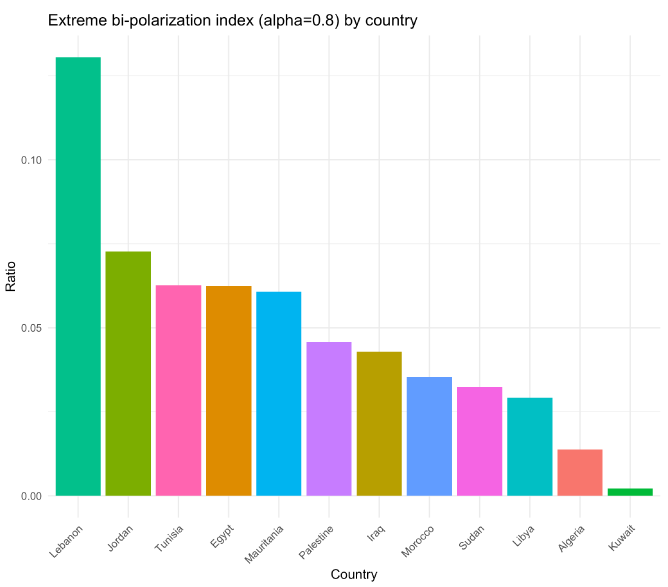

Figures 3 to 6 present the values of the extreme bipolarisation index at different levels of ![]() , demonstrating how shifting the balance between aversion to poverty and plutonomy changes the ranking of countries.

, demonstrating how shifting the balance between aversion to poverty and plutonomy changes the ranking of countries.

Lebanon: a case of extreme polarisation

The results are striking. Lebanon emerges as a dramatic outlier. Initially, with a low aversion to plutonomy (![]() ), Lebanon ranks fifth among the Arab countries in terms of the extreme bipolarisation index. As the aversion to plutonomy increases to

), Lebanon ranks fifth among the Arab countries in terms of the extreme bipolarisation index. As the aversion to plutonomy increases to ![]() , Lebanon’s ranking remains in fifth place, although the gap between Lebanon and Egypt (ranked fourth) narrows.

, Lebanon’s ranking remains in fifth place, although the gap between Lebanon and Egypt (ranked fourth) narrows.

Only when alpha reaches 0.6 do we observe notable shifts. Egypt surpasses Mauritania, and Morocco surpasses Sudan, reflecting increased sensitivity to the plutonomy that is more present in these countries. But Lebanon makes the most significant leap, rising to the top of the rankings and positioning itself above all other Arab countries. This signals Lebanon’s extreme bipolarisation, particularly when more weight is placed on plutonomy.

Between ![]() and

and ![]() , the rankings of all countries stabilise, yet the gap between Lebanon and the rest becomes stark. Lebanon’s bar on the chart is now substantially higher than the others, underscoring the country’s extreme concentration of wealth relative to poverty.

, the rankings of all countries stabilise, yet the gap between Lebanon and the rest becomes stark. Lebanon’s bar on the chart is now substantially higher than the others, underscoring the country’s extreme concentration of wealth relative to poverty.

The sharp rise for Lebanon is consistent with the findings of Assouad (2023), who argues that it is one of the most unequal countries in the world, due in part to its sectarian governance system. This system enables the ruling elite to extract large rents at the expense of the broader population, further exacerbating inequality. As Makdissi et al (2024) note, the structure is upheld by the wasta system, where ex-militia leaders offer public employment to their political supporters, reinforcing a cycle of extreme rent extraction.

Lebanon’s deep-rooted economic crisis has drastically increased poverty levels, with three in five Lebanese now living in poverty. The World Bank (2021) has highlighted that Lebanon’s financial crisis ranks among the three most severe globally since the mid-19th century.

Despite this, a small wealthy elite continues to live lavishly, as described in a recent article by Georges Malbrunot in Le Figaro, which details the extravagant lifestyles of the Lebanese wealthy few, who spend $800 on tequila in Faqra and live comfortably, far removed from the economic collapse affecting the majority of the population (Malbrunot, 2024).

Conclusion: Lebanon’s alarming polarisation

Lebanon’s dramatic rise in the extreme bipolarisation index as aversion to plutonomy increases highlights a worrying trend of inequality and social injustice. The combination of widespread poverty and extreme wealth concentration poses a significant threat to the country’s stability.

Policy-makers must urgently address the systemic factors driving this divide, particularly the extractive governance structures that enable a few to prosper while the majority struggle. Without reforms that tackle both ends of the spectrum, poverty and plutonomy, social unrest and further instability are likely to deepen.

While Lebanon represents the most extreme case, the movement of countries like Egypt and Morocco as aversion to plutonomy increases suggests that polarisation between the poor and the wealthy is a widespread issue in the region. But the picture remains incomplete due to the lack of detailed data.

Our analysis sets the extreme wealth line at $1 billion, but we observe significant fluctuations with countries like Kuwait moving in and out of the billionaires list. This indicates that extreme wealth accumulation at the level of hundreds of millions is likely to be a common phenomenon across all the countries in our study, yet remains underrepresented in our data.

This variability and the absence of finer wealth breakdowns suggest that the full scope of wealth concentration and its impacts might be even more pronounced than our current data show. Comprehensive and detailed data is essential to get a full understanding of the region’s dynamics of extreme wealth and polarisation.

In conclusion, the censored bipolarisation approach provides valuable insights into the extreme inequality in Arab countries, particularly Lebanon. It underscores the need for policies that do more than just reduce poverty; they must also address the unchecked power and influence of the wealthiest to foster a more equitable and stable society.

Further reading

Assouad, L (2023) ‘Rethinking the Lebanese economic miracle: The extreme concentration of income and wealth in Lebanon, 2005-2014’, Journal of Development Economics 161: 103003.

Atamanov, A, SA Tandon, GC Lopez-Acevedo and MA Vergara Bahena (2020) ‘Measuring monetary poverty in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: Data gaps and different options to address them’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 9259.

Makdissi, P, W Marrouch and M Yazbeck (2024) ‘Monitoring poverty in a data deprived environment: The case of Lebanon’, forthcoming in Review of Income and Wealth.

Makdissi, P, and M Yazbeck (2015) ‘On the measurement of plutonomy’, Social Choice and Welfare 44: 703-17.

Malbrunot, G (2024) ‘Tequila à 800 dollars et «fresh money»: à 150 km des bombardements, Faqra, l’entre-soi de la jet set libanaise’, Le Figaro, 31 August.

Piketty, T (2003) ‘Income Inequality in France, 1901-1998’, Journal of Political Economy 111: 1004-42.

World Bank (2021) Lebanon Economic Monitor, Spring 2021: Lebanon sinking (to the top 3).

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.