In a nutshell

According to conventional economic analysis, international financial flows stimulate industrialisation because the movement of capital provides efficient capital allocation, reduces the cost of capital, and encourages investment and growth.

New empirical evidence suggests that capital inflows lead to de-industrialisation; this is the case for medium and high-tech manufacturing industry in advanced and emerging economies, and for low-tech manufacturing industry in the Middle East and North Africa.

In emerging market and developing economies, capital flows tend to promote low-tech manufacturing, which suggests that capital inflows tend to reallocate resources from medium and high-tech manufacturing to low-tech manufacturing.

Conventional economic analysis suggests that a country’s openness to international financial flows promotes industrialisation because the movement of capital provides efficient capital allocation, reduces the cost of capital, and encourages investment and growth.

But recent research, including a study by Benigno et al (2015), is much more sceptical about the benefits of financial openness. Incorporation of capital flow management measures, including capital controls, in the suggested policy toolkit of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) can be regarded as a reflection of the shift in thinking.

Indeed, a prominent study by Rodrik (2016) finds that since the 1980s, developing economies have tended to experience declining shares of manufacturing value added in GDP – a phenomenon known as ‘de-industrialisation’. This trend corresponds to the onset of the era of globalisation, which gained momentum during the post-1990s period (Haraguchi et al, 2019).

Rodrik’s results indicate that while trade globalisation promotes manufacturing industry, openness to international financial flows – financial globalisation – leads to de-industrialisation.

This can be explained by the financial ‘Dutch disease’ argument of Corden (1994) and Palma (2005), according to which international capital flows cause exchange rate appreciation, which in turn leads to a contraction in the tradable sector. In this vein, the results of Benigno et al (2015) show that capital inflows tend to allocate resources out of manufacturing.

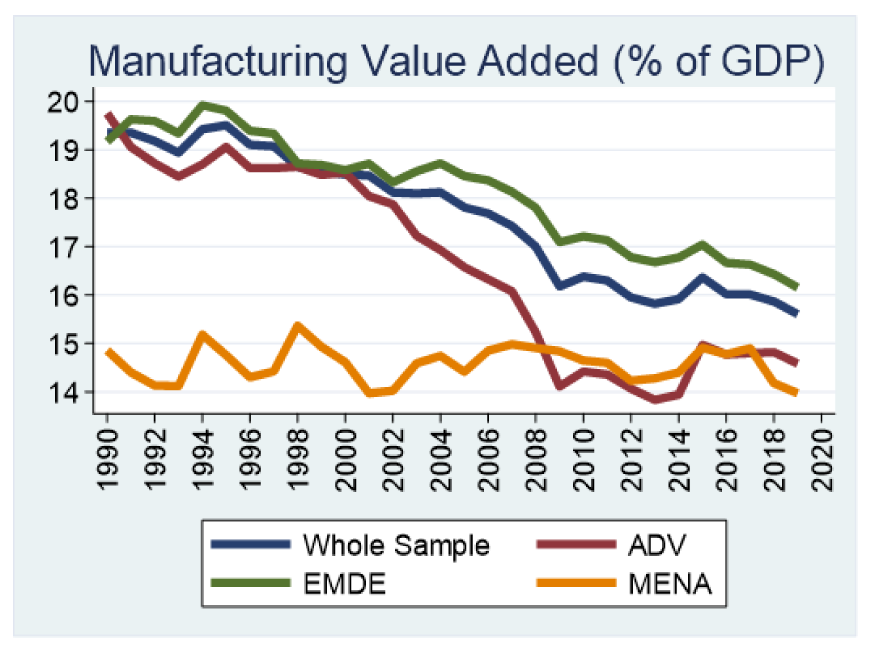

Figure 1: Evolution of manufacturing industry value added (MVA)

My new research looks at the impact of capital inflows on a range of countries over a 30-year period (Taşdemir, 2023).

Figure 1 shows the evolution of average manufacturing value added (as a percentage of GDP) over the period 1990-2019. Considering the heterogeneity of the whole sample of 84 countries, my study disaggregates the set into advanced economies (ADV), emerging market and developing economies (EMDE), and economies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Accordingly, manufacturing value added appears to diminish over the years in advanced and emerging economies. Compared with the 1990s, the gap between emerging and advanced economies tends to increase during the more recent two decades.

In MENA, manufacturing value added seems to be much lower than in advanced and emerging economies. Surprisingly, average manufacturing value added is almost the same in advanced economies and MENA during the most recent decade. Considering the decelerating trend in manufacturing value added implies de-industrialisation, this figure indicates that it is sharper in advanced economies.

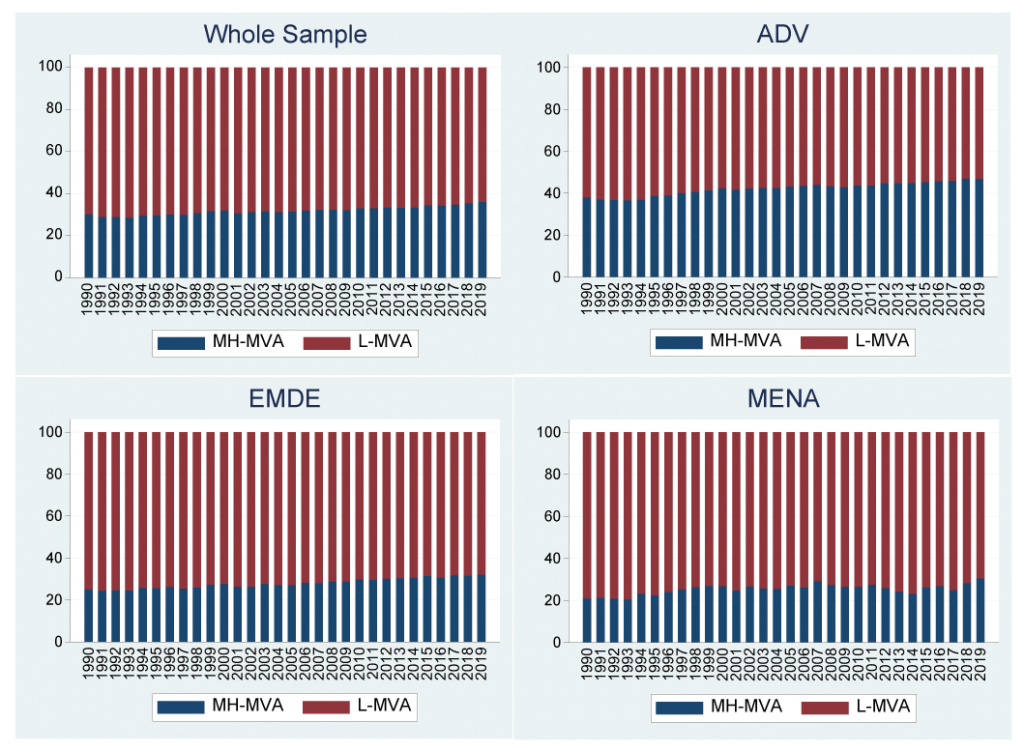

Figure 2: Manufacturing industry across technology intensity levels

The aggregate manufacturing value added exhibits widespread heterogeneity in terms of technology intensity levels. Taking this important point into consideration, my study disaggregates manufacturing value added into medium and high-tech (MH-MVA) and low-tech (L-MVA) manufacturing industries.

Figure 2 represents the shares of MH-MVA and L-MVA in the aggregate manufacturing industry over the years. Accordingly, the share of L-MVA is substantially higher than MH-MVA in the whole sample. This trend is also evident for emerging economies and MENA. The gap between MH-MVA and L-MVA is much lower in advanced economies compared with emerging economies and MENA.

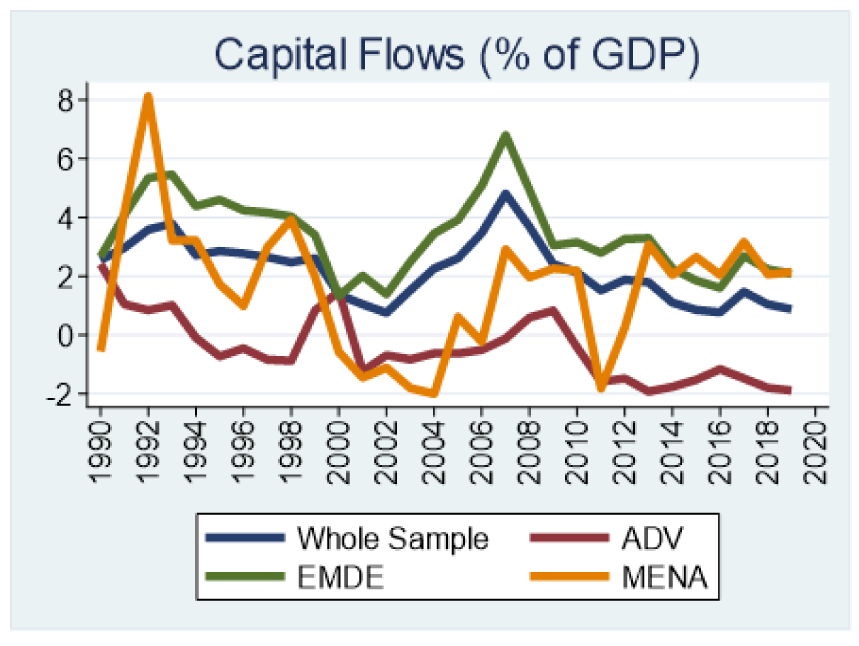

Figure 3: Evolution of capital flows

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of average capital flows, defined as the sum of the current account deficit and the change in reserves. Capital flows tend to increase until 2007 and then begin to decrease in emerging economies. Average capital flows also appear to diminish in advanced economies. In MENA, capital flows initially increase, then decrease up to the first half of the 2000s, and subsequently appear to increase during the rest of the period.

Compared with advanced and emerging economies, capital flows seem to be much more volatile in MENA. The figure also indicates that average capital flows are almost consistently positive in emerging economies and MENA, while they are negative in advanced economies. This may suggest that capital tends to move from advanced economies to emerging economies and MENA.

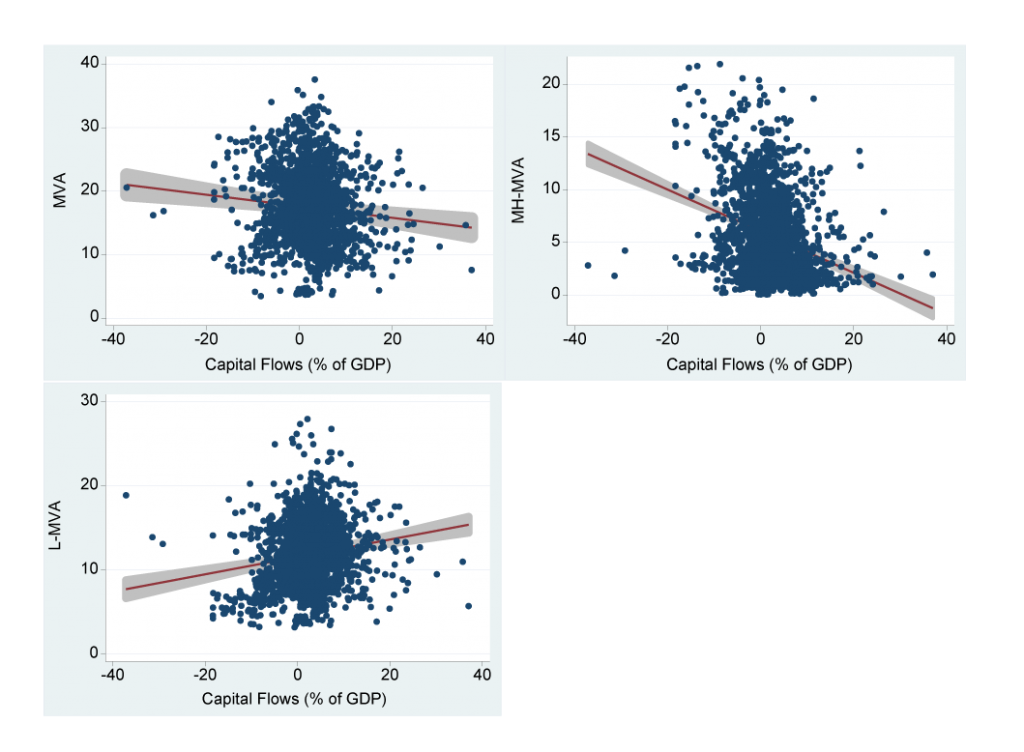

Figure 4: Scatterplot of capital flows with MVA, MH-MVA and L-MVA

Figure 4 shows the scatterplot of capital flows with manufacturing value added, MH-MVA and L-MVA for the whole sample. Accordingly, there is a negative relationship between capital flows and manufacturing value added. This may imply that an increase in capital flows tends to divert resources away from the manufacturing industry. This negative association is also evident for MH-MVA, aligning with the financial Dutch disease argument. But there is a positive relationship between capital flows and L-MVA, consistent with the theoretical benefits of financial openness.

In line with Figure 4, the empirical findings of the research suggest that capital flows lead to lower manufacturing value added in advanced, economies, emerging economies and MENA. This result contradicts the theoretical benefits of financial openness and may imply that capital flows cause financial Dutch disease by diverting resources away from manufacturing value added. Consequently, capital flows induce currency appreciation, which reduces profitability and investment opportunities in the tradable manufacturing sector.

This finding may also imply that capital flows lead to services becoming a more important part of the economy, which is the mirror image of de-industrialisation. The negative relationship between capital flows and manufacturing value added holds true for MH-MVA in advanced and emerging economies, and for L-MVA in MENA. But capital flows promote L-MVA in emerging economies, indicating a shift of resources from MH-MVA to L-MVA in this group.

Given that MH-MVA has higher productivity, de-industrialisation in MH-MVA is expected to increase productivity and income disparities. To mitigate the side effects of financial openness, the economies may consider capital flow management measures including capital controls as suggested by the IMF.

Additionally, sound and credible macroeconomic policies, flexible exchange rate arrangements, and enhanced financial development are expected to minimise the undesirable side effects of capital flows.

Consistent with remarks by Aiginger and Rodrik (2020), policy-makers may prioritise industrialisation in economic and social policies, with collaboration between the public and private sectors. Also, the movement from ‘turbo globalisation’ to ‘responsible globalisation’ along with international cooperation and solutions to problems related to globalisation may increase the success of policies.

The results of the new study imply that it is possible to finance manufacturing investment with capital flows, but it could be risky.

Further reading

Aiginger, K, and D Rodrik (2020) ‘Rebirth of industrial policy and an agenda for the twenty-first century’, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20: 189-207.

Benigno, G, N Converse and L Fornaro (2015) ‘Large capital inflows, sectoral allocation, and economic performance’, Journal of International Money and Finance 55: 60-87.

Corden, WM (1994) Economic Policy, Exchange Rates, and the International System, Oxford University Press.

Haraguchi, N, B Martorano and M Sanfilippo (2019) ‘What factors drive successful industrialization? Evidence and implications for developing countries’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 49: 266-76.

Palma, GJ (2005) ‘Four sources of “de-industrialisation” and a new concept of the “Dutch disease”’, in: Ocampo, J (ed.) Beyond Reforms: Structural Dynamics and Macroeconomic Vulnerability, Stanford University Press and World Bank.

Rodrik, D (2016) ‘Premature deindustrialization’, Journal of Economic Growth 21: 1-33.

Taşdemir, F (2023) ‘Do Capital Flows Cause (De-)Industrialization?’, ERF Working Paper No 1693.