In a nutshell

For some time now, researchers have argued that the public sector in Arab countries is too large. But this is only correct if we use the labor force (which is relatively small in Arab countries due to their low female participation rates) as a benchmark. By using an alternative metric that accounts for the role of public employment in servicing the total population and adjusting for the quality of these services, the stylized fact is reversed.

Given the importance of delivering quality public services in the context of wider economic development, it is important that policy-makers in the Arab world focus on quality, rather than simply slimming down the size of the sector. In isolation, reducing the public sector labour share will not foster the conditions for economic development in the region.

Arab countries need modern and more effective public sectors. This is particularly relevant for the poorer and conflict-afflicted countries. Rather than worrying about the size of the public sector labour force, policy-makers should keep focus on ensuring these services deliver at high quality and for all.

For some time now, researchers have argued that the public sector in most Arab countries is too large. They use public sector employment as a share of the total labour force as an indicator, but this measure is flawed in two ways. First, the public sector serves all residents, so a more relevant metric is its size relative to the entire population. Second, Arab countries have low female labour force participation rates, which means that the total labour force is smaller than in other countries. This drives up the share of public employment.

Beyond quantity, there is also the question of quality. The public employment size indicator should be adjusted for quality, especially if the question is about whether a country’s public sector is capable of enacting complex long-term structural transformation or responding to the needs of reconstruction in conflict affected countries. In this case, the ratio of public employment to total population is insufficient, unless it is adjusted by a measure reflecting the nature of public service delivery.

For these reasons, researchers and policy-makers should adopt a proposed Effective Public Employment Index (EPEI). This is the population share of public employment discounted by the government effectiveness index. The EPEI thus captures both the quantitative and qualitative aspect of public employment and is thus more relevant to understand the challenges of public employment in the Arab countries.

Most Arab countries have smaller and less effective public sectors

The size of the public sector can be explained by many factors, including: income levels; the structure of the economy; governance systems; conflict and political stability; labour market conditions; demographics; education levels; and social protection systems. The most popular benchmarks, however, are the labour force and income levels.

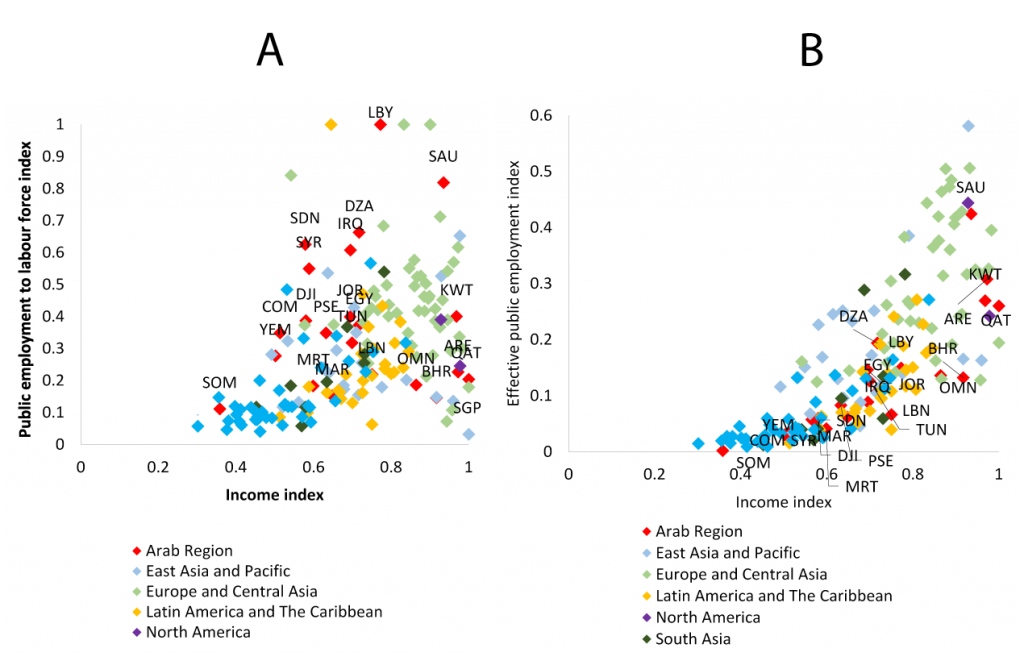

A typical argument is that Arab countries have higher share of public employment to the labour force relative to countries at comparable per-capita income levels. This can be seen in Figure 1A, which plots the income index against the public employment as a share of the labour force (normalised) for 179 countries. This figure shows that most of the Arab countries are located above the regression line, with many of them appearing as distinct outliers. This means that they have much higher public employment as a share of the labour force relative to incomes. But the picture changes dramatically with the EPEI metric. In this case, nearly all Arab countries shift below the regression line (Figure 1B), reversing the finding.

Figure 1: Income per capita and public sector employment as share of labor force (A) and Effective Public Employment Index (EPEI) (B)

Source: Author’s calculations based on public employment data from ILOSTAT and income index data from UNDP.

Notes: Public employment was taken from iMMAP for Syria , the World Bank for Libya and Independent Arabia and ilBoursa for Tunisia. Missing public employment values for other countries were retrieved from World Bank Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI). Public sector employment shares of labour force were rescaled using min-max formula. The maximum value was capped at 50. Public employment shares of total population were rescaled using min-max formula. The maximum value was capped at 20. Effective public employment index was calculated by multiplying the public employment index by rescaled government effectiveness index.

Both figures show a positive relationship between the size of the public sector and economic development. This suggests that richer countries tend to have larger and more efficient public sectors. This contradicts the long-standing view that countries should reallocate resources to the private sector as they grow richer.

The share of public employment in the total population varies significantly between oil-rich and oil-poor Arab countries. In the former, it may exceed 8%, while in the latter, it is below 3%. Since 2010, public employment to population shares have declined across all Arab countries, with the exception of Syria, where it has been rising due to overall decline in population associated with people fleeing from the conflict.

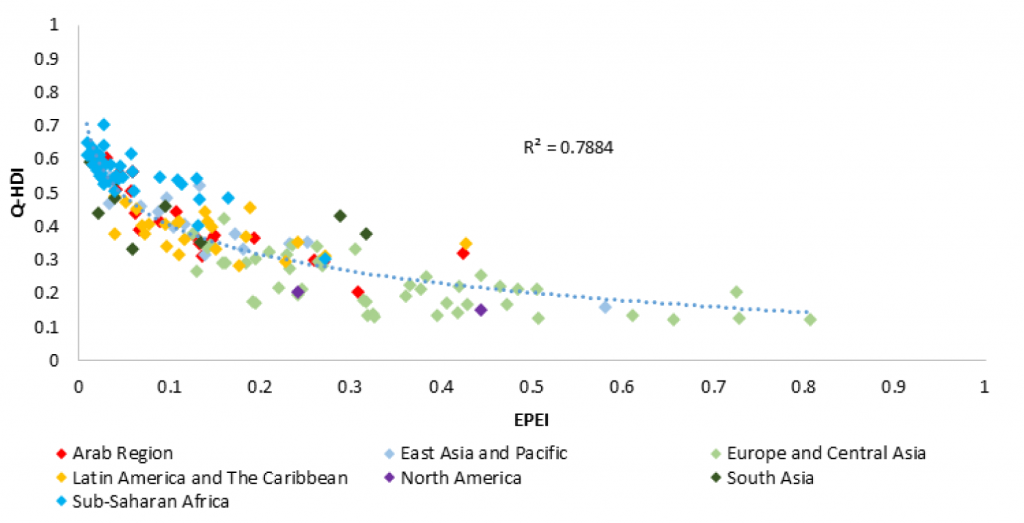

The EPEI is also useful for understanding human development achievements. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the EPEI and the quality-adjusted human development index (Q-HDI) introduced by the World Development Challenges Report (ESCWA, 2022). The non-linear relationship reflects the crucial role that delivering quality public services plays in economic development, especially early on. In many cases, this is a stage of development where governments face the highest level of policy challenges, including violent conflict and extreme political instability. It is in countries within this group where marginal improvements in the quality of public services yield the highest development dividend.

Figure 2: Public employment effectiveness and quality-adjusted human development

Source: Author’s calculations based on public employment data from ILOSTAT, government effectiveness data from World Bank World Governance Indicators (WGI) and Q-HDI data from ESCWA

Policy implications

Put together, these findings should ring the alarm bell for the Arab region. Arab countries carry the double burden of a comparatively smaller public sector compared to the size and needs of their population, together with significantly lower levels of government effectiveness (relative to any measure whether income, size of public employment or human development levels). This has serious implications for human development prospects, especially for oil-poor and conflict-afflicted countries where development challenges are highest and public employment effectiveness are lowest worldwide.

In essence, the argument here is that a more efficient public sector does not necessarily equate to a smaller one. Defining the role of the state, and especially the size of the public sector, is a complex task and subject to country-specific conditions. Lessons from successful transitions demonstrate that adequate governance reforms, rooted in a democratic environment and in conjunction with sensible economic policies, are necessary prerequisites to carry out reconstruction and peace-building activities. Simply trying to reduce the public sector labour share, without a focus on quality or local needs, will not cultivate the conditions for economic development in the region.

Arab countries need to improve the efficiency of their public sectors. This can be done by increasing transparency and accountability, implementing effective performance management systems, and investing in technology and digital infrastructure. These reforms are often inexpensive and can generate significant economic returns.

A major challenge in implementing such is resistance from public sector employees. Such reforms also need to include revisions to wages in line with expected productivity increases. The good news is that the government wage bill in the Arab world is not as bloated as some might think, averaging 9.7% of GDP during 2016-2020. This is only slightly higher than the global average of 8.9%, and is below the average for North America and East Asia and the Pacific (10.7% and 11.1%, respectively). For the oil-poor countries – where most of the region’s population live – it notably lower (7.4%). The public sector wage bill is more of a challenge to oil-rich countries, where it stood at an average of 13.4% of GDP during the same period.

The key to improving the public sector is quality, not quantity. Arab countries need modern and more effective public sectors, especially in poorer and conflict-afflicted countries. Development progress will depend on improving the provision of public services, especially in health, education, and infrastructure. Rather than worrying about the size of the public sector labour force, policy-makers should keep focus on ensuring these vital services deliver at high quality and for all.