In a nutshell

A solidarity wealth levy independent of the Arab countries’ existing public fiscal space would help to close the poverty gap and promote civic equity and unity.

A solidarity wealth tax would also dampen rent-seeking and speculative activities – and channel funds to more productive investments that increase decent employment and growth.

An emergency regional solidarity fund with a focus on social protection and food security could go a long way towards easing of most urgent humanitarian needs, and promoting regional unity.

There is a great concentration of wealth across the Arab region. In a recent study, we impute the full distribution of wealth in the region, and juxtapose it with the scale and incidence of poverty (Abu-Ismail and Hlasny, 2020). Superimposing the projected cost of closing the regional poverty gap onto the wealth distribution’s top end, it is possible to assess the scope for fiscal redistribution from the wealthiest 10% to the poor.

We conclude that the case for taxing top wealth is strong: a solidarity wealth levy independent of the Arab countries’ existing public fiscal space would go a long way towards closing the poverty gap and promoting civic equity and unity.

Key numbers

The Gini coefficient of wealth in the Arab region is 83.9, which is astounding in absolute terms as well as compared to other world regions, such as Latin America (82.8) and Africa (82.2). Even if we ignore cross-country gaps, the average national wealth Gini in Arab countries is still 73.6, putting them in the upper half of countries worldwide in terms of wealth inequality.

In 2019, the Arab region had 37 billionaires, all men, who owned as much wealth ($108 billion) as the bottom 46% of the adult population.

In March 2020, amid the outbreak of Covid-19, the billionaire list had fallen to 31 men holding $92 billion, which presumably still corresponds to the bottom half of all adults in the region experiencing asset depletion through dis-saving and depreciation.

The silver lining is that the top wealth could be tapped into as a way to fund poverty eradication. Billionaires’ wealth alone is more than double the annual budget needed to close the poverty gap across the Arab region: $38.6 billion pre-Covid-19 and $45.1 billion post-Covid-19.

Indeed, the wealthiest 10% of adults (largely hailing from Gulf Cooperation Council countries, the GCC) would barely feel it if the cost of closing the poverty gap in the least developed countries (LDCs) were charged to them. The required tax rate would be around 1% of the wealth of this group.

Introducing such a solidarity wealth tax at the level of countries, the required tax would be approximately 1.2% among middle-income countries (MICs), which is feasible, whereas among the LDCs, it would be an unworkable 44.1% of wealth of the richest decile. For the Arab LDCs and the Syrian Arab Republic, foreign assistance or other fiscal and tax revenue generation schemes are needed, such as a proposed emergency regional solidarity fund.

Wealth and unwealth – and economic growth

Poverty represents a major development challenge in the Arab region, largely due to recurring conflicts and economic recession. Poverty was not caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, but it has been accentuated by it in recent months.

At the same time, Arab countries also have substantial billionaire wealth and some of the highest levels of wealth inequality worldwide. That makes the assessment of regional wealth concentration, and the prospect of tapping it for poverty reduction purposes, very relevant socially and politically.

The past growth model in the Arab region is no longer economically feasible. As a result of ‘rentier’ growth patterns and lax fiscal policies, the sectors represented at the top of the wealth distribution, such as real estate development, attract substantial investment but contribute little to the public purse.

The share of property tax to total revenue was less than 1% in Egypt and Tunisia in 2016 and 2017, respectively. The higher return on property assets from low taxation gives rise to chronic balance-of-payments deficits, fiscal crises, especially in non-oil countries, and increasing inequality in the income and wealth distribution.

Moreover, intra-regional spillovers from oil-rich countries to oil-poor ones, which may have relieved budget pressure in the past (official development assistance, foreign direct investment and worker remittances), have significantly contracted in some countries since 2011. Their prospects for growth are minimal in the light of a projected decline in oil rents and an economic contraction as a result of Covid-19.

The potential contribution of wealth taxation is largely untapped since wealth and property taxes constitute a negligible share of total tax revenue in the Arab region, even in oil-poor countries. A solidarity wealth tax would have a positive impact on economic growth, social cohesion and decent work in the Arab region, all of which enhance prospects for peace and stability.

The proposal would significantly empower the middle class in Arab countries, thereby raising domestic consumption and investment, which would produce immediate benefits for local small and medium-sized employers, and can lead to higher and more sustained economic growth.

Regional wealth?

Information on wealth distribution is sparse, not least because of rampant concealment and tax evasion. The Panama Papers and Offshore Leaks offer a glimpse of the problem, linking thousands of regional residences, entities and officers, as well as hundreds of intermediaries to offshore accounts.

In our recent study, we assess the extent of wealth concentration and the scope for tapping top wealth for tackling poverty. We use cross-country information on the level and inequality of wealth from Credit Suisse, and information on billionaire wealth from the Forbes magazine.

We impute the full distribution of wealth in the region using parametric tendencies of wealth distributions with specific means and Gini coefficients. Imputing wealth of the top 0.5% of individuals is done by fitting the Pareto distribution, while the rest of wealth values are approximated using the lognormal distribution. This provides a smooth, realistic shape of wealth distribution for each country with the desirable level and inequality of imputed wealth values.

We find that the region had total personal wealth of $5.8 trillion as of October 2019. Of this, 76% or $4.4 trillion was held by the wealthiest 10% of adults. According to Forbes, the Arab region’s 37 billionaires (all men) alone owned about $108 billion in 2019, which is as much as wealth of the bottom 46% of the adult population. In 2020, the list has fallen to 31 billionaires holding $92 billion, which still amounts to the wealth of nearly the entire bottom half of all adults.

The regional Gini coefficient of wealth is estimated at 83.9. Even when limiting attention to within-country inequality, the average national wealth Gini is estimated at 73.6. Two Arab countries – Lebanon and Saudi Arabia – are among the 20 most wealth-unequal countries globally.

Wealth differences across the region are dazzling. The wealthiest 10% largely hail from the GCC countries, while the poorest half are mainly from their conflict-stricken and low-income neighbours, including the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen.

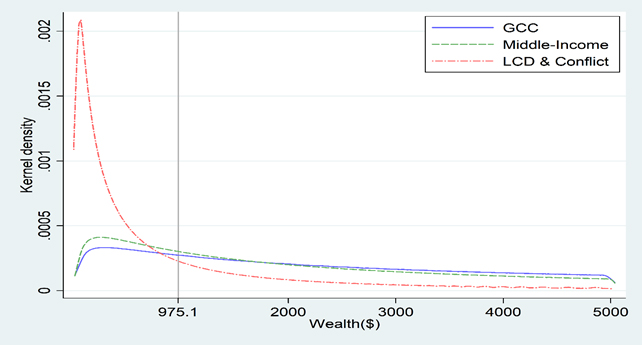

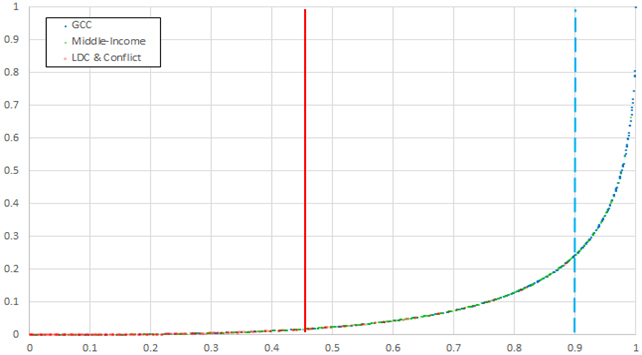

Income distributions of the different groups of countries are not aligned with one another (see Figure 1) and fall on disparate parts of the regional Lorenz curve (see Figure 2), which shows the cumulative wealth shares at different percentiles of regional adult population. The top 10% of the regional adult population have an average individual wealth of $182,939, while the bottom 46% have on average $975.

Figure 1: Income density curves for LDC and conflict, middle-income and GCC countries

Notes: Authors’ imputation based on Credit Suisse (2019) data. Density plots weighted by national population (Epanechnikov kernel, bandwidth 30), vertical line drawn at the forty-sixth percentile. GCC countries include Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Middle-income countries include Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. LDCs and conflict-affected countries include the Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen.

Figure 2: The Arab region’s Lorenz curve for LDCs and conflict-affected countries, MICs and GCC countries

Notes: Authors’ imputation using log-normal (bottom 99.5%) and Pareto (top 0.5%) parametric distributions, based on Credit Suisse (2019) data. The vertical solid red line demarcates the bottom 46% of the region’s adult population. The dashed blue line demarcates the top 10%.

Poverty costing analysis

Given that our aim is to study poverty reduction, we project the headcount and depth of poverty in each Arab country, both pre- and post-Covid-19. This is done by applying estimated growth rates and growth-poverty elasticities to existing pre-Covid-19 poverty statistics.

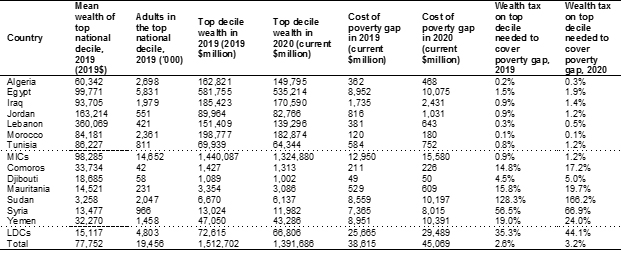

We find that the pre-Covid-19 cost of closing the poverty gap was $38.6 billion per year (Table 1) using the most recent nationally defined poverty lines, and using conservative scenarios for growth and inequality impacts (Abu-Ismail, 2020). Most of this cost is incurred in Sudan, Egypt, Yemen and Syria. Factoring in the poverty impact of Covid-19, this figure rises to $45.1 billion in 2020.

Our estimate of billionaire wealth in the region is more than double this cost of annual poverty reduction, even after the impact of Covid-19 is taken into account. While a 50% annual wealth tax on the region’s billionaires would not be workable or sustainable, expanding the tax base to the wealthiest 1% or 10% would bring the required levies to more feasible levels.

The total wealth of the top national deciles in the seven Arab MICs in 2020 is estimated at $1.3 trillion. Meanwhile, the cost of closing the poverty gaps in these countries was $12.9 billion in 2019, and $15.6 billion in 2020, accounting for the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Consequently, if there were perfect targeting of the poor in these countries, solidarity wealth taxes of, on average, 0.9% in 2019 and 1.2% in 2020 would suffice to close their poverty gaps.

Bringing LDCs into the picture, a solidarity wealth tax of around 2.6% on the wealthiest deciles would close the poverty gaps in the 13 Arab MICs and LDCs in 2019, while a 3.2% tax would do it in 2020.

In LDCs alone, the top wealth is far sparser ($66.8 billion), while the annual poverty gaps cost is higher ($29.5 billion), so the required taxes would be a prohibitive 35.3% and 44.1% on average across countries, pre- and post-Covid-19 respectively. There is simply not enough wealth at the top in these countries to plug the poverty holes. In other words, the top tails of the wealth distributions are too thin relative to the mass of income deprivation.

Table 1: Countries’ cost of closing the poverty gap and wealth of the richest decile

Notes: Authors’ estimates based on PovcalNet, using most recent reported national poverty lines and World Bank population projections from the World Development Indicators. The State of Palestine, with the cost of closing the poverty gap at $1.7 billion in 2019 and $2 billion in 2020, is missing in the Credit Suisse (2019) data, so the wealth tax cannot be computed.

Policy recommendations

Our analysis suggests that in Arab MICs, a tax on top wealth would contribute to closing the poverty gap, and instilling civic equity. In Arab LDCs, however, there is no other option but to resort to other fiscal and tax revenue generation policies and, more importantly, to external support.

An emergency regional solidarity fund with a focus on social protection and food security, such as one proposed by ESCWA (2020), could go a long way towards easing of most urgent humanitarian needs, and promoting regional unity.

Policy responses to the pandemic in Arab countries should focus first and foremost on the need for enhanced food security and social protection, by ensuring adequate access to affordable food, especially in the Arab LDCs, and by extending the coverage of existing schemes, including access to healthcare, cash transfers, food aid and unemployment benefits, some of which are already in place in many MICs.

A fair and progressive taxation system supported by political will and strong institutional capacity can raise the revenues required to meet the financing needs of these poverty reduction interventions without imposing any additional fiscal burden in many Arab countries.

Moreover, the notion of a solidarity wealth tax should be rooted in a commitment to wealth redistribution, reflected in pro-poor initiatives that are supported by the richest decile and that have a direct positive impact on the most vulnerable social groups.

The solidarity wealth tax may have many other positive spillover effects. In addition to its positive impact on poverty and many other social indicators, a solidarity wealth tax would dampen rent-seeking and speculative activities, and channel funds to more productive investments that increase decent employment and growth.

It may also lead to improving tax and customs administration, simplifying coding and regulation, and investing in technology to improve transparency is necessary to enhance compliance. Over time, these efforts support a broader culture of tax compliance and greater revenues, which is a top priority in Arab countries (ESCWA, 2017).

One practical way to improve transparency and accountability is requiring all citizens and residents to file income tax returns, even if not all actually pay tax – an approach encouraged recently in many developing countries, such as India. More transparency on income and wealth would also allow ministries of finance, social affairs and related institutions to improve poverty targeting practices.

To gain public confidence, it is essential to have a wide public policy dialogue on the appropriate tax rate. A variable tax rate can be useful to mitigate land and real estate speculation, which is rampant in some Arab countries. But introducing variable tax rates can, like exemptions, increase the complexity of tax systems, and raise associated administrative costs in implementation.

Since wealth taxation is not an adequate policy option for the Arab LDCs, the ESCWA proposed emergency national policy response is a more realistic short-term solution. Arab governments are called on to establish a regional social solidarity fund that supports vulnerable countries, including the Arab LDCs, particularly during times of crisis.

The fund should target the poor and vulnerable, ensure a rapid response, and provide relief during food shortages, health emergencies and other disasters. For it to succeed, it is vital that the richer GCC countries fully support this proposed emergency fund.

Further reading

Abu-Ismail, Khalid (2020) ‘Impact of Covid-19 on Money Metric Poverty in Arab Countries’, ESCWA.

Abu-Ismail, Khalid, and Vladimir Hlasny (2020) ‘Wealth inequality and the cost of poverty reduction in Arab countries: the case for a solidarity wealth tax’, ESCWA.

ESCWA (2020) ‘Regional Emergency Response to Mitigate the Impact of Covid-19’.

ESCWA (2017) ‘Rethinking Fiscal Policy for the Arab Region’, E/ESCWA/EDID/2017/4.