In a nutshell

Because the Middle East and North Africa region has limited resources, it will have to rely on innovative design and development of low-cost and scalable ways to contain or eliminate the spread of Covid-19.

The business community, civil society and diasporas have stepped in to propose solutions in disparate areas, such as fund-raising, production of masks and other medical equipment, and communication campaigns.

But the health issues cannot be solved without simultaneously tackling the underlying flaws of MENA economies and societies, including lack of fair competition, lack of access to digital technology and a poor business environment.

The Covid-19 crisis and its dual shock of disease and falling oil prices have brought to light the underlying flaws of economies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) today – flaws that authorities must fix if the region is to prosper.

At the global level, there will likely be a ramping up of the role of the state to eradicate the virus and protect economies from depression. State intervention is already high in the MENA region (see Figure 1). How well this helps countries cope first with the pandemic and then its aftermath depends on their ability to refocus, to be more transparent and to develop accountability mechanisms.

Figure 1. Government consumption in GDP

In many respects, the Covid-19 pandemic is a crisis of preparedness – or lack thereof. Successful models for limiting the spread of the virus – such as in the Republic of Korea – quickly deployed technology (including digital contact tracing) to fight Covid-19 and targeted assistance to those in need. These models should be analysed, replicated and adjusted – they create issues for data protection and privacy.

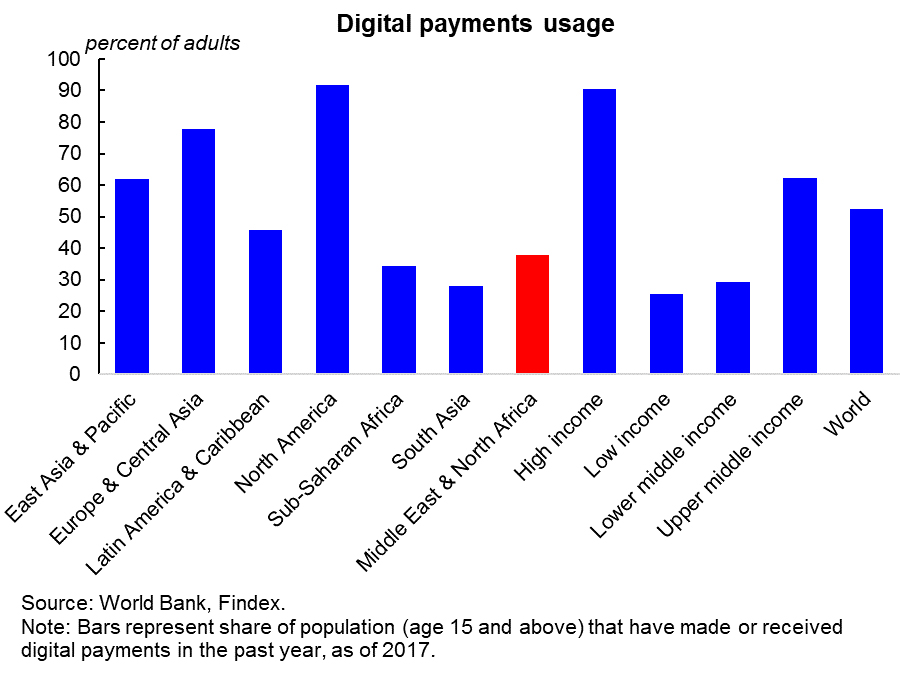

But MENA countries lag behind other parts of the world in technology adoption including digital payments (see Figure 2). Moreover, the region risks facing dramatic consequences if governments do not become more transparent and increase information flow.

Increased transparency and information availability should reduce citizen mistrust of authorities – or at least force authorities to behave better. By helping ensure that cash transfers actually get to their targets – and not to government cronies – increased transparency and data disclosure will not only strengthen government legitimacy, but also accelerate economic recovery and limit the rise in poverty.

Figure 2: Digital payments usage

Because the region has limited resources, it will have to rely on innovative design and development of low-cost and scalable ways to contain or eliminate the spread of Covid-19.

Interestingly, the business community, civil society, and diasporas have stepped in to propose solutions in disparate areas such as fund-raising, production of masks and other medical equipment, and communication campaigns. But the health issues cannot be solved without simultaneously tackling the underlying flaws of MENA economies and societies:

- Production systems limited by policies that promote overvalued exchange rates and lack of fair competition.

- Highly educated young people, especially women, hampered by lack of access to digital technology and a poor business environment.

- Governments should encourage emerging innovations and create space for a genuine private sector as a new and sustainable engine of growth, replacing pork barrel spending.

MENA has to move away from the corrosive duality of a split informal and formal society. The pandemic has left the informal sector flat-footed, making it an even riper source of unrest than before the novel coronavirus emerged. And the collapse in oil prices, which shows no signs of abating but lots of potential to worsen, will essentially end the patronage economy.

In other words, events that are out of authorities’ control will trigger change in MENA societies. Governments must decide whether that change will be guided or traumatic and unpleasant.

To move to more equal and less contentious societies, countries must simplify and promote a universal social protection system to replace the current fragmented systems that benefit the few and exclude the many. They must provide a universal basic income for all, which would help promote innovation by making it safer to take risks, as well as universal health systems. To finance them, societies will have to find new sources of revenue, including through tax system reforms.

Productivity should be enhanced through the promotion of fair competition and the adoption of digital technology, especially in finance and telecommunication. These improvements would be especially important to the informal sector, as it would gain access to services and markets previously accessible only to the privileged few and state-owned enterprises.

Any guided change should be associated with reforms of the role of the state. In most MENA countries, the number of public administration and state-owned enterprise employees is high – partly due to the long-standing social contract and partly as employment of last resort.

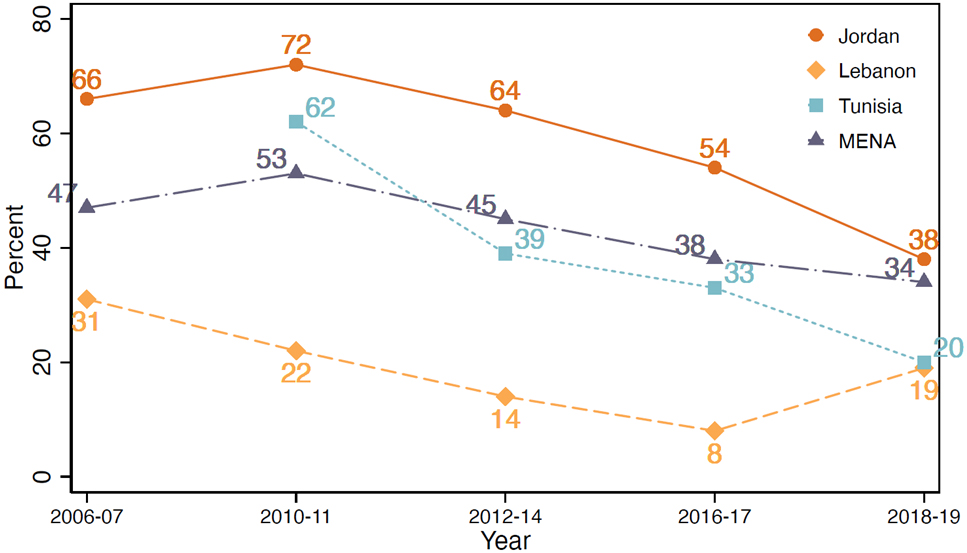

The unravelling of the old, inequitable social contract (see Figure 3) should be combined with public service reforms that retain talented workers and remove unfair protections, while providing universal social protection and healthcare.

Figure 3: Trust in government

Source: Arab Barometer.

Note: Each marker represents the share of population who trust the government to a great or medium extent. MENA is weighted estimates of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen, when available.

These necessary measures will be funded by tax and other fiscal reforms, as well as by savings from the large reduction by the state in loss-making and redundant commercial activities, and increased tax revenues that will occur once the business sector starts operating more transparently.

Having a more efficient and accountable public administration focused on key state functions such as promoting universal health and other social services, and ensuring that fair competition puts an end to the rent-seeking behaviour that has hindered growth in the MENA region, will empower the millions of educated women and men hoping to ride a wave of innovation towards prosperity.

This article was originally published on OECD Development Matters as part of a series on tackling Covid-19 in developing countries. Read the original article.