In a nutshell

While the unprecedented stimulus packages adopted by GCC governments will support growth and accelerate the economic recovery, it will cause a wider fiscal deficit at least for the next couple of years, amid lower oil revenues.

GCC governments should defer any austerity measures to the post-recovery phase, and target a near-term vision to implement a countercyclical fiscal stance and sustain the growth of non-energy sectors for more diversification.

Taking into consideration their realistic budgetary breakeven oil prices, GCC countries should improve the efficiency of their fiscal management and reduce unproductive spending, to ensure higher growth and fiscal sustainability over the medium term.

Given the speed and magnitude of the Covid-19 outbreak across the world and the region, GCC countries are expected to experience a drastic economic slowdown due to a combination of forced business closures, travel restrictions and supply chain disruptions that have hit the retail, transport, travel and hospitality sectors hard.

In addition, the collapse in global oil prices triggered by weaker demand and higher supply, has hit government revenues and weakened fiscal positions in GCC countries. Oil prices have tumbled by more than 70% since the beginning of this year, falling to around $20 per barrel by the end of April. Combined with the sharp decline in the global demand, estimated at around 70 million barrels per day, the oil sector is expected to experience a real decline in 2020.

In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected a contraction of growth in the GCC of 2.7% in 2020. In addition to the contraction in the oil sector, this drop is reinforced by a projected decline of 4.3% in the non-oil sector during this year, a significant downward revision from the 2.3% growth projected in the October 2019 World Economic Outlook.

The rescue packages may not be enough

In response to this challenging environment, GCC countries have adopted economic stimulus measures worth billions of dollars to soften the pandemic effects and support business recovery. Governments have implemented income protection measures for households, and enhanced consumer protection measures to prohibit price increases amid supply shortages attributed to disruptions of supply chains.

Most central banks in the region have cut their interest rates, relaxed their capital and liquidity regulatory requirements, offered targeted relief measures to protect banks’ customers affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as scaling back other lending restrictions, to support lending activities to the private sector.

Policy measures have also targeted more support to small and medium-sized enterprises by deferring loan repayments, extending concessional loans and reducing fees. GCC authorities have also targeted support and relief measures to firms in the most affected sectors, such as retail, banking, air transport, hospitality and non-food manufacturing.

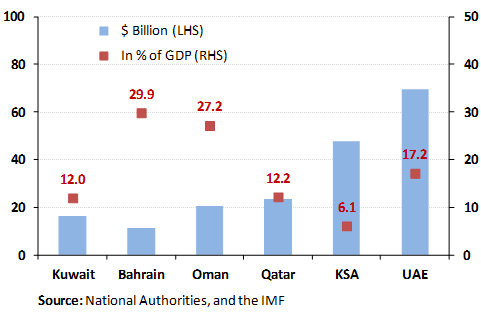

Figure 1: Stimulus packages adopted by GCC governments

But these policy measures – ranging from $16.5 billion in Kuwait to $70 billion in the UAE (United Arab Emirates) – appear so far not to be enough to protect the region from an economic slowdown. The debate is once again about the need to mobilise additional economic packages to mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 outbreak and to boost economic activity in the most affected sectors, especially if economic disruptions from the pandemic and lower oil prices last longer than expected.

Wider fiscal deficit, the other side of the coin

While the unprecedented fiscal stimulus adopted by GCC governments will support growth and accelerate the economic recovery, it will also cause a wider fiscal deficit at least for the next couple of years. In fact, despite the long range of economic and social development strategies adopted by all GCC countries to promote sustainable development in the non-hydrocarbon sector, oil prices remain the main driver of economic growth in the region.

Even in the UAE, which is the most diversified economy of the GCC, oil revenues are transmitted to the economy through their large share in financing the government’s budget and therefore spending that has been intertwined with private economic activity and investors’ confidence.

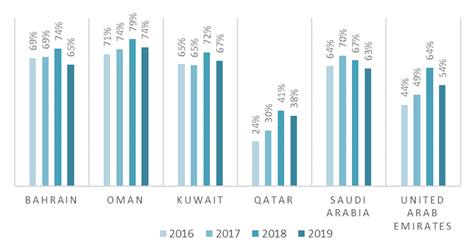

Figure 2: Share of hydrocarbon revenues (% of total government revenues)

Source: IMF. Numbers reported for Kuwait correspond to fiscal years.

Thus, the hydrocarbon sector continues to account for over half of real economic output, and more than 70% of budget revenues and export earnings across many GCC countries. The fiscal breakeven prices for all GCC countries are higher than the projected Brent price average of $35 in 2020. This implies that GCC countries are likely to experience a deterioration in their fiscal positions, widening fiscal deficits with larger needs for financing and debt issuance.

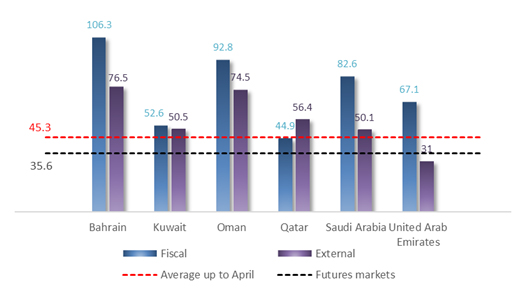

Figure 3: Fiscal and external breakeven prices

Source IMF Regional Economic Outlook (April 2020)

As per the external current account position, oil prices are currently below the external breakeven prices for many GCC countries, implying projected wider deficits. At the current and future oil prices, and given the large share of hydrocarbon exports, the current account of the balance of payments in most GCC countries is expected to deteriorate further, putting pressures on foreign international reserves that could constrain the countries’ capacity to issue external debt in the international market.

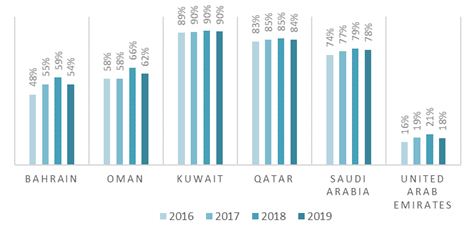

Figure 4: Share of hydrocarbon exports (% of total exports)

Source: IMF

While it is difficult to estimate the full economic damage from the coronavirus outbreak, it is already clear that the pandemic will have severe negative effects on GCC economies, especially if the oil price remains low for long. As a result, GCC countries’ fiscal and external deficits are expected to deteriorate further to a double-digit range in 2020, amid lower oil prices and higher fiscal stimulus.

In this context, the GCC economies are facing a complicated challenge. On the one hand, supporting economic recovery requires increasing fiscal stimulus and preserving priority for public capital spending. On the other hand, rising capital spending, coupled with the projected decline in government revenues, raises the need for financing, causing a significant increase in the budget deficit.

Striking the necessary balance between fiscal consolidation and economic recovery?

The decline of oil revenues could force a pro-cyclical fiscal stance to stem the increase in budget deficits. Against a backdrop of lower revenues, limited international reserves and constraints to safeguard the stability of the exchange rate peg, some governments may be forced to cut capital spending immediately, remove subsidies and implement new taxes and fees, to keep their fiscal deficit targets and to ensure fiscal and external sustainability.

But adopting fiscal consolidation will magnify the negative effect of the crisis on the non-oil sector, and even counter the efficiency of the huge stimulus packages that are in the pipeline to contain the impact of the virus on the economy, raising concerns about striking a balance between fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability.

Even if the speed of the economic recovery depends largely on the longevity of the lockdown and the end of the pandemic, the effectiveness of stimulus packages plays an important role in speeding up this recovery. In fact, it appears that even under a complete lifting of lockdown, say by the end of Q2, it would take a long time before the GCC economies return to normal, suggesting a U-shaped recovery rather than a V-shaped one.

Seasonality could also play a role as Q3 growth is usually the weakest for economic activity in the GCC. Moreover, given the large share of the expatriate population, labour policies could affect the speed of recovery. Massive layoffs in the summer could further slow down aggregate demand and shrink domestic consumption, countering the effectiveness of stimulus packages.

Therefore, GCC governments should continue their efforts, especially during the lockdown, to support the private sector and foster investors’ confidence, to minimise the adverse impact of the coronavirus on business activity. Countries with large financial buffers and good credit ratings could capitalise on these options to finance growing deficits in the short run. Any delay of supporting the hardest hit sectors or cutting necessary capital spending for private sector growth would negatively affect the growth momentum and recovery of the non-oil sector.

To that end, GCC countries, where fiscal space permits, should postpone fiscal consolidation until achievement of the economic recovery. Once recovery is at full speed, fiscal reforms should take priority to adjust to the new normal of ‘low for long’ oil prices. That is, the medium-term plan should prioritise fiscal reforms to increase the efficiency of public spending, especially on infrastructure and development projects, diversify non-oil revenues and ensure fiscal sustainability.

Appropriate funding options

Given that fiscal stimulus is inevitable to deal with pandemic effects and the growth slowdown, GCC governments should focus on optimising their spending and then look for the appropriate options to finance their budget deficits. As government revenues are highly dependent on oil activities, several countries in the region are expected to experience a significant reduction in their fiscal resources.

Consequently, some countries in the region already initiated debt issuance in international markets to compensate for the funding shortfalls caused by low crude prices and the coronavirus outbreak.

Saudi Arabia increased its debt ceiling to 50% of GDP from a previous 30% ceiling in March. To that end, Saudi Arabia issued $7 billion worth of dollar-denominated bonds on 15 April, while Qatar issued $10 billion worth of bonds. Similarly, the government of Abu Dhabi sold bonds worth $7 billion, seeking to counter slumping oil prices.

The projected significant withdrawals of financial savings following the shrinking oil revenues may force most GCC countries to continue to issue more debt over the next few years, amid low interest rates in the international market, to sustain the twin deficits, and maintain the stability of the peg. Bahrain, Oman and Saudi Arabia could become significant debtors over the coming period, as their financing needs are expected to exceed their current liquid financial buffers, against the backdrop of lower oil prices.

Moreover, financing debt requires careful macroeconomic management to avoid potential crowding out of the private activity that could erode investors’ confidence. The declines in oil revenues and domestic economic activity are likely to have increased liquidity pressures on the domestic financial system.

Rising public debt could have further adverse effects on economic growth if it is financed heavily from the domestic market, particularly from the banking sector and/or coupled with drawing down government deposits. Under this scenario, domestic liquidity could be at risk, particularly for countries where central banks do not have adequate international reserves to shore up liquidity in the domestic markets.

To avoid crowding out private lending in the banking sector, budget deficits in GCC countries could be financed with asset drawdown, where financial buffers are comfortable, as well as domestic and external debt issuance, where debt levels are low. Debt issuance, however, should be managed with a medium-term strategy that ensures debt sustainability and the return on government spending in terms of stimulating further growth.

But even if government debt stocks remain low by international standards, a persistent fiscal deficit, coupled with a larger deficit of the external current account, could cause a rapid rise in debt stocks in the short run. This might jeopardise fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability unless debt financing is managed within a medium-term strategy that maximises growth potential and diversifies non-oil revenues in the budget.

More focus on the long-term vision

In each crisis, there is always a silver lining. It is worth mentioning that low oil prices and the coronavirus outbreak provide yet another opportunity to expedite the path of the announced reform visions that have started years ago in the wake of the structural break of the oil price in 2014.

The hardships endured by the adverse implications of the Covid-19 crisis will force GCC governments to defer many austerity measures to the post-recovery phase. The short-term priorities will be focused on speedy and effective implementation of countercyclical policies that are likely to be costly in terms of a wider fiscal deficit and more borrowing.

Post-recovery and taking into consideration their realistic breakeven oil prices, GCC countries should improve their fiscal financial management with the main goals of increasing efficiency and reducing unproductive spending. Medium-term fiscal management should be anchored on a gradual increase in the fiscal primary balance to ensure debt sustainability and a gradual decrease in the need for borrowing.

Enduring fiscal deficits in the near term is not a problem, but managing and financing those deficits without compromising non-oil growth and debt sustainability objectives are the key challenge.

The bigger challenge for GCC countries is to stay the course of further diversification to decrease dependency on oil resources. To that end, managing the fiscal balance and adopting fiscal stimulus must be consistent with long-term economic priorities to maximise the return on non-energy growth.

While governments are supporting companies to prevent insolvencies, they should avoid permanent subsidies that will persist after the crisis or which could help uncompetitive sectors to endure. Stimulus packages should be conditional on business recovery and contributions to growth, with the main targets being to ensure business continuity, increased outputs and sustain employment growth.

In parallel, fiscal policy should ensure adequate social safety nets, and provide temporary and targeted tax relief, and transfers to the most vulnerable groups to ensure sustainable inclusive growth.

Adopting this long-term approach would pave the way for gradually decreasing government spending and dependency on oil revenues, underpinned by robust progress towards more diversification of GCC economies led by non-energy growth and solid private sector activity.