In a nutshell

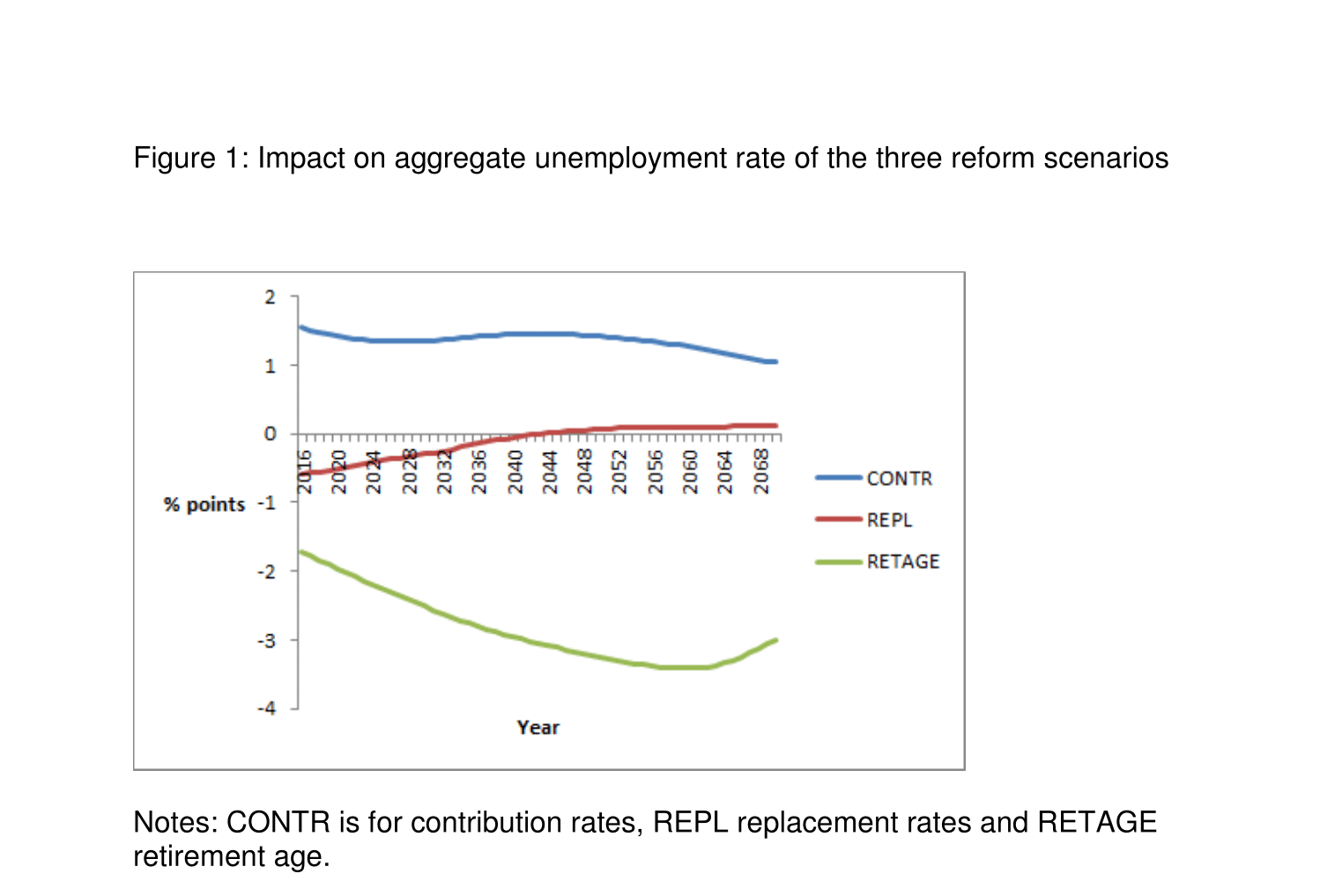

Higher contribution rates produce the least desirable outcome in terms of unemployment, particularly for the youngest workers.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, a higher statutory retirement age does not entail an increase in youth unemployment, but rather the reverse.

Achieving sustainability for the region’s pension systems is the central objective, but other challenges should not be neglected, including increasing the system’s coverage, especially in rural areas, and improving the pensions of the poorest.

Even though the pension systems of the Arab world typically exclude a significant share of the working population, they are still too expensive and unsustainable. In Tunisia, for example, which has the second highest share of older people in the region after Lebanon, the pension system is already in deficit. Tunisia’s pension deficit is partly financed from the healthcare fund, which endangers both systems.

With rising life expectancy and urbanisation, all other countries in the region will face similar problems sooner or later. In some, the estimated liabilities of the pension system are higher than the public debt. A recent World Bank report (Arab Monetary Fund and World Bank, 2017) confirms the fears expressed by the same and other institutions over a decade ago (Robalino, 2005).

The difficulty is that all reform options are unpopular: increasing social security contributions reduces net wages or increases unemployment; decreasing the pension level reduces the welfare of retirees; and increasing the statutory retirement age is often considered to be bad news by the middle-aged and particularly those close to reaching retirement.

Given that the region is in a period of political instability, governments avoid unpopular decisions. They tend to focus on short-term management issues. But as the Tunisian example shows, the longer that reforms are postponed, the higher will be the cost for the population. As some argue, it is also unfair for the younger generation to pay for a much more generous pension system than the one from which they will ultimately benefit.

The responsibility of economists in such a critical period is to assess the costs and benefits of different pension reforms and present the results in a transparent way to inform public opinion. Given the persistence of high unemployment rates in the region, particularly for youth, the impact on jobs of the various scenarios is particularly sensitive.

In recent research, a colleague and I present the likely impact of three options for pension reform on the labour market and intergenerational equity (Ben Othman and Marouani, 2016):

- Higher social security contributions.

- Reducing pension levels (through lower replacement rates).

- Or increasing the statutory retirement age.

While technically and politically the easiest to implement, there is a consensus among economists that increasing pension contribution rates has negative effects on labour demand and thus on unemployment.

Lower pension levels reduce the purchasing power of retirees and can thus lead them to seek jobs to get complementary incomes. It can also have an impact on their consumption, particularly on the products that they demand relatively more than the average, such as health products.

Increasing the effective retirement age is becoming relatively consensual. But there is a common belief that if older people stay longer in the active population, there is a risk of lower job opportunities for youth. One of the objectives of our pension study is to check the accuracy of this conventional wisdom.

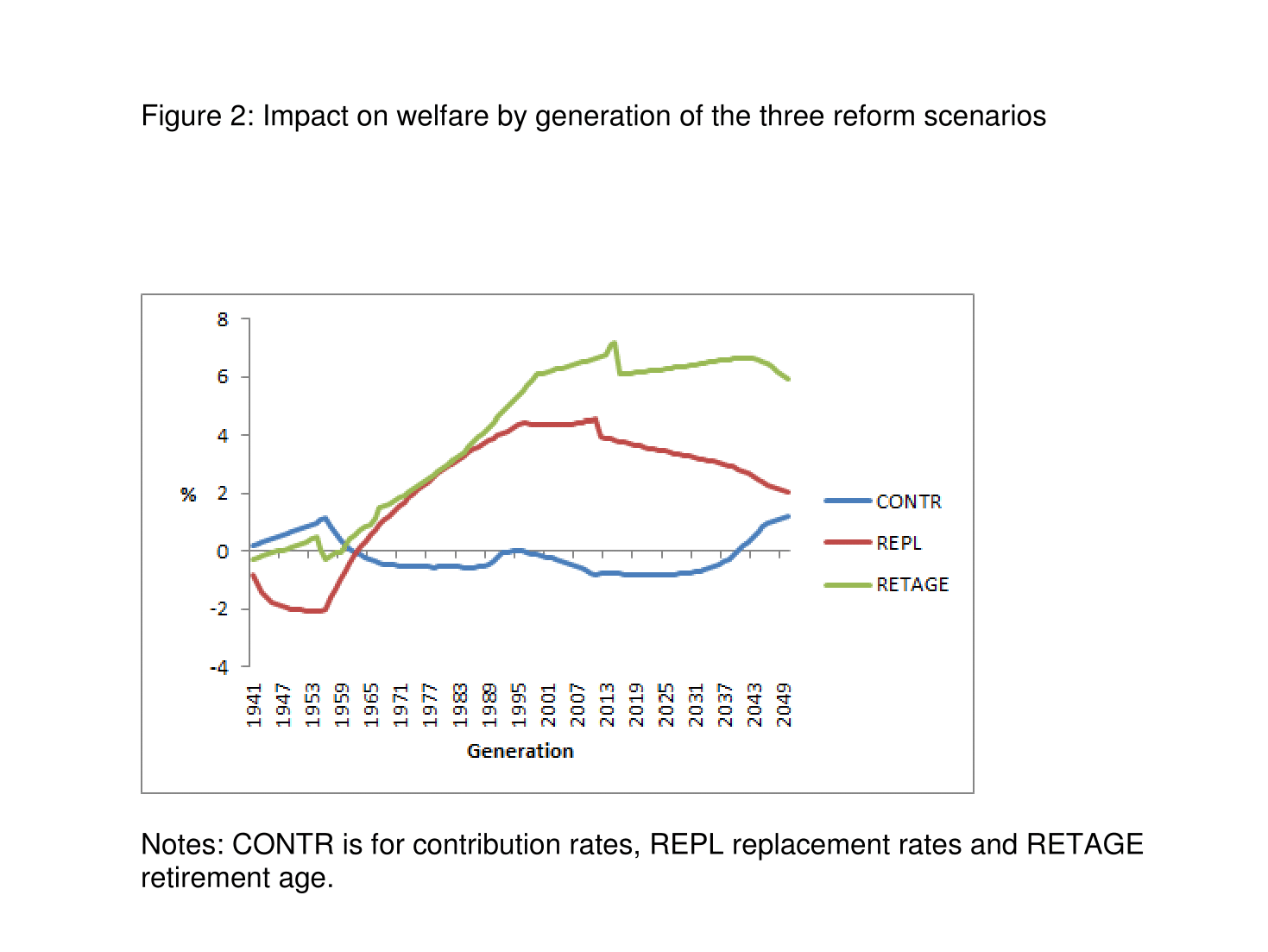

The first conclusion of our study is that increasing contribution rates is the worst solution in terms of welfare, except for current retirees who pay lower income taxes and no longer contribute to the social security system.

The replacement rate reform scenario has a positive impact on all generations born after 1963. The generations that lose the most are current retirees and particularly young pensioners. There is a reduction of welfare for generations at the end of their working lives because the benefits of lower taxes do not cover the costs of lower pensions.

The retirement age reform has a positive impact on welfare for all generations, except current retirees who are not affected by the increase in the length of the working life.

For the two scenarios where aggregate welfare increases, the middle-aged are those that benefit most from the reform. The reforms increase the implicit taxation stemming from the pay-as-you-go system on the older and youngest generations while the middle-aged bear a much lower cost.

Moreover, higher contribution rates produce the least desirable outcome in terms of unemployment, particularly for the youngest workers. Lower replacement rates do not have a significant effect on the labour market.

Finally, contrary to conventional wisdom, a higher statutory retirement age does not entail an increase in youth unemployment, but rather the reverse. Indeed, a higher retirement age has a negative impact on older workers’ labour supply.

This is due to the increase in the number of years in which they can earn a higher income, which allows them to devote less time to work during their last years of activity. This decrease in older workers’ labour supply induces substitution by the youngest workers who constitute the cheapest labour category. Part-time schemes for older workers implemented in some countries (such as Singapore) could be a solution to accompany the increase in the statutory retirement age.

Although the issue of the sustainability of the system is central, it must not hide other challenges for the region. These include increasing the coverage of the pension system (especially in rural areas) and improving the pensions of the poorest by increasing their density of contribution (Ben Braham and Marouani, 2016). One way to achieve these goals is to tighten the link between benefits and costs for contributors.

Further reading

Arab Monetary Fund and World Bank (2017) Arab Pension Systems: Trends, Challenges and Options for Reforms, World Bank Open Knowledge Repository.

Ben Braham, Mehdi, and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2016) ’Determinants of Contribution Density of the Tunisian Pension System: A Cross Sectional Analysis’, ERF Working Paper No. 1005.

Ben Othman, Mouna, and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2016) ‘Labour Market Effects of Pension Reform: An Overlapping Generations General Equilibrium Model Applied to Tunisia’, ERF Working Paper No. 1019.

Robalino, David (2005) Pensions in the Middle East and North Africa: Time for Change, World Bank Open Knowledge Repository.