In a nutshell

Until recently, the elderly in most Arab countries have benefited from intergenerational solidarity, provided with assistance by their children.

With ageing populations, low social security benefits and inadequate family support, a significant number of older people, especially women, will end up living in very bad conditions during their retirement.

To reduce financial hardship and poverty in old age, it will be necessary to extend access to those people who are currently excluded from social security programmes.

The number of people in the world who are aged 60 and over is set to rise from 962 million today to 2.1 billion in 2050 (United Nations, 2017). In the Arab countries, where the total population in this age group was 3.9 million in 1950 and 16.5 million in 2000, it is now 28 million and continuing to grow at an accelerating pace. In nine countries in the region – Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Tunisia – there will be more people over 60 than children under 15 by 2050.

The Arab countries are also experiencing significant gains in life expectancy at old age, which in turns raises issues about the quality of life and health of the elderly. Research shows, for example, that women in Arab countries can live longer but experience worse health conditions in old age (Al Hazzouri et al, 2011; Abdulrahim et al, 2013). While the average number of years that a woman aged 60 is expected to live is 20, the average number of years that a woman aged 60 is expected to live in good health is barely 14.

As long as fertility rates continue to decline and life expectancy continues to rise, older people will steadily increase as a proportion of the population. Ageing is inevitable: without an adequate social policy, poverty at old age will increase. Providing economic security and healthcare for the elderly is one of the key challenges in the region where the elderly face a high risk of poverty and vulnerability.

A growing number of studies highlight the effectiveness of social security programmes in protecting people from the risk of poverty, and specifically the effectiveness of public pension expenditure in reducing poverty rates among pensioners (Albuquerque et al, 2010; Rupp et al, 2003; Engelhardt and Gruber, 2004; Franco et al, 2008).

In almost all Arab countries, pension programmes are provided through social protection programmes, but their coverage is limited to a small fraction of the population. Except in Lebanon, Arab countries have mandatory ‘defined benefits’ public pension schemes. Lebanon has a ‘defined contribution’ national provident fund.

The Algerian scheme is the oldest, established in 1949 by the French colonial power. The Egyptian scheme followed later (in 1955), then Morocco (in 1959) and Tunisia (in 1960). Iraq (1956), Libya (in 1957), Syria (1959), Saudi-Arabia (1962), Jordan (1956), Oman (1975), Bahrain (1976), Kuwait (1976), Yemen (1990) and the UAE (1999).

Most pension systems in the region are unsustainable, accumulating very high pension liabilities due to high replacement rates (for civil servants) and very low contribution rates. Since their introduction, there have been no major changes and pension reforms in these countries.

A recent report (Arab Monetary Fund and World Bank, 2017) highlights the urgent need to reform the pension system in the region. Improving the efficiency of pension systems – reducing costs, improving investment strategies and governance; improving the sustainability, equity and affordability of pension programmes and expanding coverage of pensions are the main challenges facing the region.

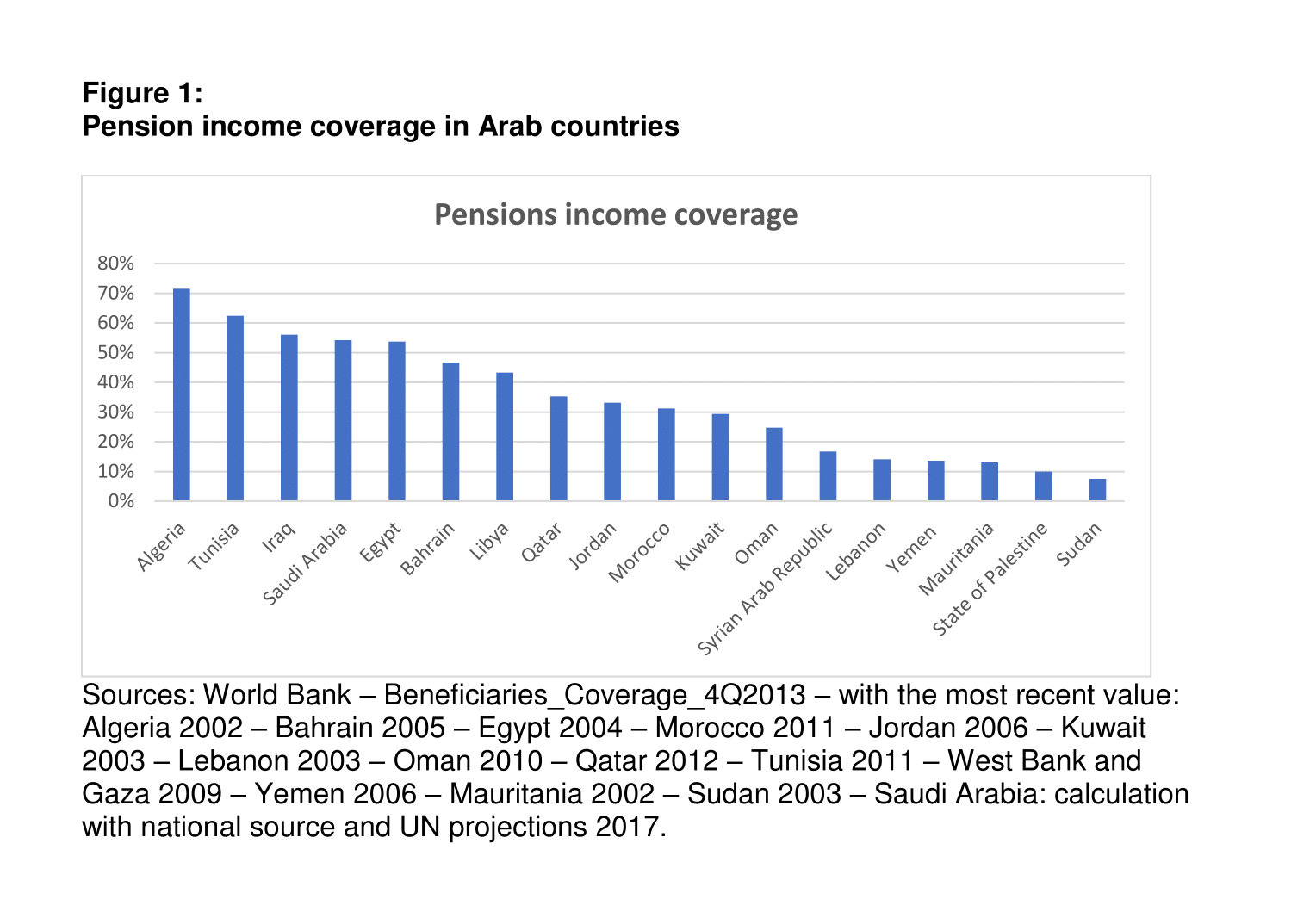

What’s more, large groups of the population in Arab countries remain outside pension programmes, mainly women, the self-employed and those working in agriculture and the informal sector. On average, the pension coverage rate for the region does not exceed 35% of the workforce.

Pension income coverage varies drastically between Arab countries – from a low of 8% in Sudan to a high of 72% in Algeria (see Figure 1). On the high end of the spectrum, over 50% of the elderly population in Tunisia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt benefits from pension coverage, while in high-income Gulf countries, pension income coverage is 47% in Bahrain, 35% in Qatar, 29% in Kuwait and 47% in Oman. At the bottom of the class, the situation is the least favourable in Palestine and Sudan with around 10% pension income coverage.

In Palestine, coverage extends exclusively to workers in the public sector and non-governmental organisations. Formal old age assistance programmes are available primarily through the Ministry of Social Affairs and aid programmes funded by the European Union, the United Nations and the World Bank. But these programmes are limited in scope and depend entirely on foreign donors. They cannot therefore guarantee beneficiaries either a regular income or sustainable payments.

In some countries, there is no protection at all for the elderly. This is the case in Jordan and Tunisia (see Table 1). Arab women in these countries are in the most vulnerable situation with no access at all to social security benefits. Employed in the informal sector or in unpaid work, they are not eligible for social insurance (pension entitlement and health insurance programmes) when they get older.

Until recently, the elderly in most Arab countries have benefited from intergenerational solidarity. But demographic trends and social changes are likely to have a negative impact on the traditional system where family and children play a central role in providing assistance to the elderly.

We can expect that with ageing, low social security benefits and inadequate family support, a significant number of older people, especially women, will end up living in very bad conditions during their retirement. They are also likely to face chronic diseases, dementia and mental illness without any healthcare support.

In this context, if we are to reduce financial hardship and poverty in old age, it will be necessary to extend access to those people who are currently excluded from social security programmes, to guarantee a minimum pension that takes account of their standard of living. Furthermore, specific programmes have to be implemented for workers without formal employers.

Further reading

Abdulrahim, Sawsan, Kristine Ajrouch and Toni Antonucci (2015) ‘Aging in Lebanon: Challenges and Opportunities’, The Gerontologist 55(4): 511-18.

Al Hazzouri, Zeki, Mehio Sibai, Monique Chaaya, Ziyad Mahfoud and Kathryn Yount (2011) ‘Gender Differences in Physical Disability among Older Adults in Underprivileged Communities in Lebanon’, Journal of Aging Health 23(2): 367-82.

Albuquerque, Paula, Manuela Arcanjo, Vitor Escaria, Francisco Nunes and Jose Pereirinha (2010) ‘Retirement and the Poverty of the Elderly: The Case of Portugal’, Journal of Income Distribution 19(2-4): 41-64.

Arab Monetary Fund and World Bank (2017) Arab Pension Systems: Trends, Challenges and Options for Reforms, World Bank Open Knowledge Repository.

Engelhardt, Gary, and Jonathan Gruber (2004) ‘Social Security and the Evolution of Elderly Poverty’, Berkeley Symposium on Poverty, the Distribution of Income, and Public Policy.

Franco, Daniele, Maria Rosaria Marino and Pietro Tommasino (2008) ‘Pension Policy and Poverty in Italy: Recent Developments and New Priorities’, Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia 67: 119-60.

Rupp, Kalman, Alexander Strand and Paul Davies (2003) ‘Poverty among Elderly Women: Assessing SSI Options to Strengthen Social Security Reform’, Journal of Gerontology 58B: 359-68.

United Nations (2017) ‘World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision’, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, United Nations.